Poetry review – PHOENIX: Neil Fulwood is moved and encouraged by the spirit of reconciliation and collaboration running through this collection by Antony Owen

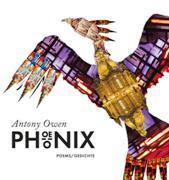

Phoenix

Antony Owen

Thelem Press

ISBN 978-3-95908-522-9

£20.00

Phoenix

Antony Owen

Thelem Press

ISBN 978-3-95908-522-9

£20.00

Along with London and Birmingham, the city of Coventry took the worst of the Luftwaffe’s ministrations during World War 2. Similarly, “Bomber” Harris’s onslaught against Dresden was nothing short of genocide, a firestorm that anyone who has read Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five will shudder to think about.

Astoundingly, The Coventry German Circle came into being in 1946. Its founding principle – as stated in an afterword to this collection – is the facilitation of “informal gatherings and discussion in a spirit of peace and reconciliation”. Five years later, the Anglo-German Association was formed. Its Dresden wing, Die Deutsche-Britische Gesellschaft Dresden E.V., was integral, along with The Coventry German Circle, in bringing Antony Owen’s Phoenix to fruition.

Equally important were translators Bettina Jansen, Diana Hellwig, Elisabeth Humboldt, Eric Piltz, Franca Funke, Lynne Adams, Monika Campbell, Rainer Barczaitis, Sebastian Jansen, Stephen Lamb and Wieland Schwanebeck; visual artists Alexandra Müller, Ashley Spindler, Christian Manss, John Yeadon, Karen Koschnick, Kerstin Franke-Gneuss, Lucas Oertel, Matthias Bausch, Monika Marten and Volker Lenkeit; the Coventry/Dresden Arts Exchange; and the dignitaries whose commendations open the collection: Ann Lucas, Lord Mayor of Coventry; Dirk Hilbert, Lord Mayor of Dresden; the Very Reverend John Witcombe, Dean of Coventry; and the Reverend Angelika Behnke, Frauenkirche Pastor.

If this review thus far sounds more like a list than an actual review, I make no apologies. It may be Anthony Owen’s name on the cover, but Phoenix is a collaborative project of staggering reach and ambition – a collaboration not just between artists and translators, but between cities; even, in the timeliness of its release, between the war-torn past and a troubled and divisive present.

As the supposedly “sunlit uplands” of Brexit continue to reveal themselves as cloud-sheathed wastelands, as xenophobia continues to define mainstream political discourse, as dogwhistle rhetoric continues to muscle out dignity and statesmanship, and as an increasingly radicalised and polarised populace embraces ever more toxic outlets – far right extremism masquerading as a crusade for personal freedom here, unforgiving “cancel culture” judgementalism there – Phoenix is unquestionably the book the world needs right now. It is a book that reminds us, often in unflinchingly direct terms, that common ground, reconciliation, forgiveness and brotherhood aren’t just lofty ideals but a genuine alternative, forged in blood and love and fearlessness, from which a better future can be built.

The poems in Phoenix are drawn from Owen’s previous collections The Nagasaki Elder (V. Press), which was shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award in 2017, and The Unknown Civilian (Knives Forks & Spoons Press), supplemented by hitherto unpublished works. Most tackle the horrors of war and/or the complacency of peace. Some are specifically about Dresden or Coventry, others reach back to the Great War, others leap forward to recent conflicts; PTSD and the fall out back in civvy street are never far away. Some examples:

In Dresden

it would be a crime not to touch

wicks of fingers pointing to God,

and take gold rings engraved with their names.

Identify them.

These dead firemen’s buckets filled

with initialled rings weigh heavy.

[‘Inferno’]

In the smouldering amnion of New Coventry,

a singed dog dragged to water on its arse

licks the old nails deeper into his spleen.

A postman stands in the flame-grey postcode,

staring at doorways with chimneys around them,

meaning as they open to charred occupants.

[‘Postman in the Smoke’]

There is no armistice for soldiers who know the fib of poppies,

who know that the dead blow back bugles of fungi.

[‘The Last Minute of Wilfred Owen’s Life’]

It came quickly to take them away.

They never knew if the flames were Russian or British,

but it came nonetheless; and flames can make you so cold if you survive them.

[‘When It Snows in Aleppo’]

I wonder in those brief Pay Pal unions

of credit card wanks and smileys

if hotgirl97 misses you at all.

I wonder if Ray got home after mourning you

those twenty-two days of hard whiskey,

fighting to be heard by headless suits.

[‘The Suicide of Private John Doe’]

There are also poems about Stalingrad, the Falklands and 9/11. ‘The Falling Man’ says more in 15 lines about that terrible day in modern American history than Don DeLillo’s similarly titled novel does in 256 pages. I’m tempted to quote ‘The Falling Man’ in full, but this review is arguably overloaded with quotes already.

I’m also conscious that I’ve simply lumped that plethora of quotes together without commentary or close reading. This is partly because I wanted to give the prospective reader of Phoenix some indication of the collection’s raw power; its sustained intensity. And it’s also partly because Owen’s work simply doesn’t need the fine-tooth-comb explication of line-by-line analysis. Owen writes poetry of a blazing immediacy.

In an age where the epithet “war poet” anchors one to a specific era or theatre of conflict, Owen has dedicated his career to being a “peace poet”, a vocation that, to my way of thinking, seems like a hard decision to have made; a hard path to follow. But an essential one. Owen is a humanitarian as well as an artist. Yet there’s nothing preachy or hand-wringing in the verses he crafts. He gets his hands dirty. He pulls on his boots and wades into the blood and guts of the aftermath. He sifts and assesses the remnants with both a forensic eye and a heart that’s heavy with a sense of loss.

Military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously said that “war is a mere continuation of politics by other means”. Satirist Ambrose Bierce define peace as “international affairs, a period of cheating between to periods of fighting”. Both statements are weighted with accuracy; neither even begins to consider the complex interrelationship between what we all too horribly recognise as war and all too foolishly convince ourselves is peace. Antony Owen’s work exists in this hinterland, a lIght in dark times, a guide by which we might correct our course, an urgent reminder that – as Jo Cox unforgettably put it – “we have more in common than that which divides us”.

Oct 26 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Antony Owen

Poetry review – PHOENIX: Neil Fulwood is moved and encouraged by the spirit of reconciliation and collaboration running through this collection by Antony Owen

Along with London and Birmingham, the city of Coventry took the worst of the Luftwaffe’s ministrations during World War 2. Similarly, “Bomber” Harris’s onslaught against Dresden was nothing short of genocide, a firestorm that anyone who has read Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five will shudder to think about.

Astoundingly, The Coventry German Circle came into being in 1946. Its founding principle – as stated in an afterword to this collection – is the facilitation of “informal gatherings and discussion in a spirit of peace and reconciliation”. Five years later, the Anglo-German Association was formed. Its Dresden wing, Die Deutsche-Britische Gesellschaft Dresden E.V., was integral, along with The Coventry German Circle, in bringing Antony Owen’s Phoenix to fruition.

Equally important were translators Bettina Jansen, Diana Hellwig, Elisabeth Humboldt, Eric Piltz, Franca Funke, Lynne Adams, Monika Campbell, Rainer Barczaitis, Sebastian Jansen, Stephen Lamb and Wieland Schwanebeck; visual artists Alexandra Müller, Ashley Spindler, Christian Manss, John Yeadon, Karen Koschnick, Kerstin Franke-Gneuss, Lucas Oertel, Matthias Bausch, Monika Marten and Volker Lenkeit; the Coventry/Dresden Arts Exchange; and the dignitaries whose commendations open the collection: Ann Lucas, Lord Mayor of Coventry; Dirk Hilbert, Lord Mayor of Dresden; the Very Reverend John Witcombe, Dean of Coventry; and the Reverend Angelika Behnke, Frauenkirche Pastor.

If this review thus far sounds more like a list than an actual review, I make no apologies. It may be Anthony Owen’s name on the cover, but Phoenix is a collaborative project of staggering reach and ambition – a collaboration not just between artists and translators, but between cities; even, in the timeliness of its release, between the war-torn past and a troubled and divisive present.

As the supposedly “sunlit uplands” of Brexit continue to reveal themselves as cloud-sheathed wastelands, as xenophobia continues to define mainstream political discourse, as dogwhistle rhetoric continues to muscle out dignity and statesmanship, and as an increasingly radicalised and polarised populace embraces ever more toxic outlets – far right extremism masquerading as a crusade for personal freedom here, unforgiving “cancel culture” judgementalism there – Phoenix is unquestionably the book the world needs right now. It is a book that reminds us, often in unflinchingly direct terms, that common ground, reconciliation, forgiveness and brotherhood aren’t just lofty ideals but a genuine alternative, forged in blood and love and fearlessness, from which a better future can be built.

The poems in Phoenix are drawn from Owen’s previous collections The Nagasaki Elder (V. Press), which was shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award in 2017, and The Unknown Civilian (Knives Forks & Spoons Press), supplemented by hitherto unpublished works. Most tackle the horrors of war and/or the complacency of peace. Some are specifically about Dresden or Coventry, others reach back to the Great War, others leap forward to recent conflicts; PTSD and the fall out back in civvy street are never far away. Some examples:

In Dresden it would be a crime not to touch wicks of fingers pointing to God, and take gold rings engraved with their names. Identify them. These dead firemen’s buckets filled with initialled rings weigh heavy. [‘Inferno’] In the smouldering amnion of New Coventry, a singed dog dragged to water on its arse licks the old nails deeper into his spleen. A postman stands in the flame-grey postcode, staring at doorways with chimneys around them, meaning as they open to charred occupants. [‘Postman in the Smoke’] There is no armistice for soldiers who know the fib of poppies, who know that the dead blow back bugles of fungi. [‘The Last Minute of Wilfred Owen’s Life’] It came quickly to take them away. They never knew if the flames were Russian or British, but it came nonetheless; and flames can make you so cold if you survive them. [‘When It Snows in Aleppo’] I wonder in those brief Pay Pal unions of credit card wanks and smileys if hotgirl97 misses you at all. I wonder if Ray got home after mourning you those twenty-two days of hard whiskey, fighting to be heard by headless suits. [‘The Suicide of Private John Doe’]There are also poems about Stalingrad, the Falklands and 9/11. ‘The Falling Man’ says more in 15 lines about that terrible day in modern American history than Don DeLillo’s similarly titled novel does in 256 pages. I’m tempted to quote ‘The Falling Man’ in full, but this review is arguably overloaded with quotes already.

I’m also conscious that I’ve simply lumped that plethora of quotes together without commentary or close reading. This is partly because I wanted to give the prospective reader of Phoenix some indication of the collection’s raw power; its sustained intensity. And it’s also partly because Owen’s work simply doesn’t need the fine-tooth-comb explication of line-by-line analysis. Owen writes poetry of a blazing immediacy.

In an age where the epithet “war poet” anchors one to a specific era or theatre of conflict, Owen has dedicated his career to being a “peace poet”, a vocation that, to my way of thinking, seems like a hard decision to have made; a hard path to follow. But an essential one. Owen is a humanitarian as well as an artist. Yet there’s nothing preachy or hand-wringing in the verses he crafts. He gets his hands dirty. He pulls on his boots and wades into the blood and guts of the aftermath. He sifts and assesses the remnants with both a forensic eye and a heart that’s heavy with a sense of loss.

Military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously said that “war is a mere continuation of politics by other means”. Satirist Ambrose Bierce define peace as “international affairs, a period of cheating between to periods of fighting”. Both statements are weighted with accuracy; neither even begins to consider the complex interrelationship between what we all too horribly recognise as war and all too foolishly convince ourselves is peace. Antony Owen’s work exists in this hinterland, a lIght in dark times, a guide by which we might correct our course, an urgent reminder that – as Jo Cox unforgettably put it – “we have more in common than that which divides us”.