Poetry review – A SPELL IN THE WOODS : In spite of lockdown Rachael Smart is able to enjoy a captivating walk in woodland with the aid of Stella Wulf’s poetry

A Spell in the Woods

Stella Wulf

Fair Acre Press

ISBN 978-1-911048- 50-3

36pp £7.50

A Spell in the Woods

Stella Wulf

Fair Acre Press

ISBN 978-1-911048- 50-3

36pp £7.50

During the past year lockdown circumstances have limited human access to landscape and we have seen flora and fauna flourish in our absence. It feels timely, then, that Fair Acre Press have recently published Stella Wulf’s A Spell in the Woods, a collection of vibrant and closely observed meditations on creatures and the natural world with the lens firmly on giving voice to all that is wild.

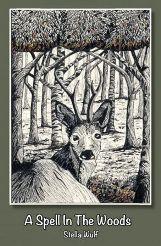

Language is enhanced by art in this collection and Wulf, who writes under a pseudonym, is also Claire Jefferson, an artist concerned with capturing landscape. The poems in this collection are accompanied by exquisite line drawings in pen and ink with just a smudge of colour. The illustrations are heavy on black contrast and make limited use of white space to ensure the finest of detail. This fusion of word and picture gives the wild a rare accessibility and also fires reader’s senses at multiple levels.

Within these thirteen poems, Wulf gives the stage to a glut of woodland creatures who are brought to life via monologue, fairy tale retellings and folklore with a discerning naturist’s eye. Once deep in the reading of these poems there is a sense of timelessness, a casting off of our vacuous, too fast world with a sharply honed focus on the minutiae of non-human behaviours amongst the marvel of the changing seasons. Wulf often characterises wild creatures in an anthropomorphic way to invite readers to identify with more familiarity; but she also illuminates human responsibility in hunting, consumption and waste.

In ‘Crow’ ‘All that lies between his world/ and mine is a thin, brittle pane.’ The poem explores the magnetism of human and animal looking in on one other from all too often disparate worlds, the bedroom window the fragile partition that divides the two. Here, readers are given space to see the ease with which we adopt negative associations to wildlife and hence to re-think ancient habits. Although this bird is ‘Intent on shattering the myth of himself /as dread clarion, bringer of doom’, the speaker sees their reflection ‘…drawn/ in the ink of his eye.’ This poem serves as a paradox for it not only turns the absurdity of human superstition on its head with the first-person narrator supporting the crow’s cause, but also works subtly to reinforce that same speaker in bed looking out on the passage to the otherworld.

Fairy tales are woven throughout the collection and they deliver fresh, slant perspective on outdated models of female capture. In ‘Pigs Might Fly’ a woman’s domestic entrapment with a farmer who keeps pigs is told in an oral storytelling style with rhyming verse which gives hard matter to soft words. ‘She smarted with the salt of his keeping, /wept buckets of tears at every squealing,’ Despite a deliberate obliqueness the reader is taken towards bodily fluids and sexual violence, an anguish which becomes even more unsettling when coupled with the pigs might fly hyperbole: ‘He said she could leave when pigs might fly/’ This sombre poem comes into well-lit relief by the last stanza, though, for it comes full circle and she makes his (death) bed where ‘…he will lie till the pigs grow wings.’ We find our female survivor in a satisfying break from conventional fairy tale sexual politics.

The Swanhilde story is re-told from first-person perspective in ‘Swan Maiden’, a theatrical piece which has real linguistic climax and encapsulates all the grace and harmony of the ballet. We find a woman, once again trapped by a male, who shapeshifts into a swan after dark: ‘…By night I let fly /my bombilations, a trumpeting lament ’ The performance rises in pace and pattern when she re-claims a swan suit from her male keeper and assonance is shot throughout: ‘slipping’ ‘stolen shift’ ‘stretch out’ ‘spreading pool’ ‘in the slick’, an arresting, agile fusion of s sounds which build to a standing finale: ‘I open my wings, stretch out my neck,’ Language, at the height of sensory impact, here, gifts us the movement of a dancer open-bodied and triumphant in her concluding act.

Wulf’s ear for harmony is a striking feature in her command of language. These poems feature delightful strings of ripe, full words arranged for chime when spoken aloud, words which stretch sound as far as it can go. ‘Wales Sings’ describes ‘gospels of shafted light,’ ‘the plainsong of slate’ ‘to wring the hearts of man’, clusters which hold a deep lyrical balance. Another example is ‘A Spell in the Woods’ which brings us an A-Z of trees in five couplets, words arranged with poignancy and a pleasing syllabic regularity. ‘Wych elm, elder, aspen, oak / badger’s hideout, hedgepig’s poke.’ Tree names and animal homes form a melodic list of woodland life repetitive enough to mimic a trance or spell; and then this is contrasted, sharply, with a damning reference to human damage and commerce: ‘Chain saw, bulldozer, open sores / Tesco, Poundland, British Home Stores.’

This is a beautiful collection which takes readers off-track to observe a natural world flushed with life and movement. Fairy tale politics and folklore bring complexity to the poems and a fresh perspective much needed, particularly in respect of female narratives. The minutiae of landscape and wildlife is so often taken for granted by humans that it is barely seen and this book not only serves as a stunning visual and lyrical reminder, as seen through a naturist’s eyes, but also provides a deeply evocative wander through the woods at a time when wandering has not been permitted, and this is what makes A Spell in the Woods even more valuable.

Apr 11 2021

London Grip Poetry Review – Stella Wulf

Poetry review – A SPELL IN THE WOODS : In spite of lockdown Rachael Smart is able to enjoy a captivating walk in woodland with the aid of Stella Wulf’s poetry

During the past year lockdown circumstances have limited human access to landscape and we have seen flora and fauna flourish in our absence. It feels timely, then, that Fair Acre Press have recently published Stella Wulf’s A Spell in the Woods, a collection of vibrant and closely observed meditations on creatures and the natural world with the lens firmly on giving voice to all that is wild.

Language is enhanced by art in this collection and Wulf, who writes under a pseudonym, is also Claire Jefferson, an artist concerned with capturing landscape. The poems in this collection are accompanied by exquisite line drawings in pen and ink with just a smudge of colour. The illustrations are heavy on black contrast and make limited use of white space to ensure the finest of detail. This fusion of word and picture gives the wild a rare accessibility and also fires reader’s senses at multiple levels.

Within these thirteen poems, Wulf gives the stage to a glut of woodland creatures who are brought to life via monologue, fairy tale retellings and folklore with a discerning naturist’s eye. Once deep in the reading of these poems there is a sense of timelessness, a casting off of our vacuous, too fast world with a sharply honed focus on the minutiae of non-human behaviours amongst the marvel of the changing seasons. Wulf often characterises wild creatures in an anthropomorphic way to invite readers to identify with more familiarity; but she also illuminates human responsibility in hunting, consumption and waste.

In ‘Crow’ ‘All that lies between his world/ and mine is a thin, brittle pane.’ The poem explores the magnetism of human and animal looking in on one other from all too often disparate worlds, the bedroom window the fragile partition that divides the two. Here, readers are given space to see the ease with which we adopt negative associations to wildlife and hence to re-think ancient habits. Although this bird is ‘Intent on shattering the myth of himself /as dread clarion, bringer of doom’, the speaker sees their reflection ‘…drawn/ in the ink of his eye.’ This poem serves as a paradox for it not only turns the absurdity of human superstition on its head with the first-person narrator supporting the crow’s cause, but also works subtly to reinforce that same speaker in bed looking out on the passage to the otherworld.

Fairy tales are woven throughout the collection and they deliver fresh, slant perspective on outdated models of female capture. In ‘Pigs Might Fly’ a woman’s domestic entrapment with a farmer who keeps pigs is told in an oral storytelling style with rhyming verse which gives hard matter to soft words. ‘She smarted with the salt of his keeping, /wept buckets of tears at every squealing,’ Despite a deliberate obliqueness the reader is taken towards bodily fluids and sexual violence, an anguish which becomes even more unsettling when coupled with the pigs might fly hyperbole: ‘He said she could leave when pigs might fly/’ This sombre poem comes into well-lit relief by the last stanza, though, for it comes full circle and she makes his (death) bed where ‘…he will lie till the pigs grow wings.’ We find our female survivor in a satisfying break from conventional fairy tale sexual politics.

The Swanhilde story is re-told from first-person perspective in ‘Swan Maiden’, a theatrical piece which has real linguistic climax and encapsulates all the grace and harmony of the ballet. We find a woman, once again trapped by a male, who shapeshifts into a swan after dark: ‘…By night I let fly /my bombilations, a trumpeting lament ’ The performance rises in pace and pattern when she re-claims a swan suit from her male keeper and assonance is shot throughout: ‘slipping’ ‘stolen shift’ ‘stretch out’ ‘spreading pool’ ‘in the slick’, an arresting, agile fusion of s sounds which build to a standing finale: ‘I open my wings, stretch out my neck,’ Language, at the height of sensory impact, here, gifts us the movement of a dancer open-bodied and triumphant in her concluding act.

Wulf’s ear for harmony is a striking feature in her command of language. These poems feature delightful strings of ripe, full words arranged for chime when spoken aloud, words which stretch sound as far as it can go. ‘Wales Sings’ describes ‘gospels of shafted light,’ ‘the plainsong of slate’ ‘to wring the hearts of man’, clusters which hold a deep lyrical balance. Another example is ‘A Spell in the Woods’ which brings us an A-Z of trees in five couplets, words arranged with poignancy and a pleasing syllabic regularity. ‘Wych elm, elder, aspen, oak / badger’s hideout, hedgepig’s poke.’ Tree names and animal homes form a melodic list of woodland life repetitive enough to mimic a trance or spell; and then this is contrasted, sharply, with a damning reference to human damage and commerce: ‘Chain saw, bulldozer, open sores / Tesco, Poundland, British Home Stores.’

This is a beautiful collection which takes readers off-track to observe a natural world flushed with life and movement. Fairy tale politics and folklore bring complexity to the poems and a fresh perspective much needed, particularly in respect of female narratives. The minutiae of landscape and wildlife is so often taken for granted by humans that it is barely seen and this book not only serves as a stunning visual and lyrical reminder, as seen through a naturist’s eyes, but also provides a deeply evocative wander through the woods at a time when wandering has not been permitted, and this is what makes A Spell in the Woods even more valuable.