Poetry review – DRESSING FOR THE AFTERLIFE: Neil Fulwood finds that Maria Taylor’s energetic collection covers a lot of ground

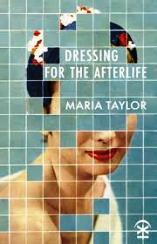

Dressing for the Afterlife

Maria Taylor

Nine Arches Press

ISBN 978-1-913437-01-5

£9.99

Dressing for the Afterlife

Maria Taylor

Nine Arches Press

ISBN 978-1-913437-01-5

£9.99

Maria Taylor’s long-awaited new collection is bookended by poems about running. Here are the opening lines of ‘She Ran’:

I took up running when I turned forty.

I opened my front door and started running

down a filthy jitty and past my parents’ flat.

Aptly, this is an off-the-blocks kind of poem, a poem of movement and energy in which Taylor sprints through a potted autobiography. It fizzes with energy and an exuberant use of language. That wonderful phrase “a filthy jitty” is soon joined by the likes of “I ran past all my exes, even a few crushes / who sipped mochas and wore dark glasses” and “I ran in a wedding dress that scattered confetti / and was cheered by the cast of Star Wars”.

‘Woman Running Alone’ is harder to pull a handy two or three line quote from. It consists of two sentences, the first of which unspools through nineteen lines while the second is left purposefully unfinished. The other reason I’m not going to quote from it is because it deserves to be discovered in precisely the place it occupies: the final page of the collection, where it acts as both a thematic re-encapsulation and, in its refusal to end on a full stop, a continuation of Dressing for the Afterlife’s central theme of movement; a pushing forward to whatever Taylor publishes next.

It’s a lazy critic who takes their prompts from other reviews, but a recent appraisal by Alan Baker on the Litter website is worth mentioning, particularly his identification of “two forces operating; one is pushing the poetry to be the standard poetry of the British mainstream variety … and another pushing it towards something much more interesting, which is unpredictable, language-driven and exciting”.

Therefore the movement that propels Dressing for the Afterlife isn’t just thematic – movement as in physical motion, movement as in geographical displacement/immigration, movement as in the multitasking necessitated by motherhood, movement as in interaction/intertextuality (nimbly and wittily explored in ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’) and movement as in moving pictures – but an integral component of Taylor’s linguistic and poetic capabilities.

There is much, then, to discover, discuss and deconstruct here – which leads me to the part-caveat-part-apology that I’ve thrown out in a couple of previous reviews here on London Grip: that I don’t want to overdo the analysis in favour of preserving the joy of discovery for the reader; that I don’t want to quote too much from the collection, no matter how tempting it is to stud the review with snippets; and that I don’t always want to contextualise the quotes I do use. Such as these:

Rain makes no apologies. A gate-crasher

at a wedding who drops hints

into fluted glasses.

[‘The Fields’]

Not for gossip with backcombed wives

will she wear her alchemist’s overalls.

[‘Anna of the Fisheries’]

Summer was up. My spine curled

into a question mark ...

[‘The Boyfriend’]

There are turns of phrase that linger and that you catch the flavour of like a memory surfacing; turns of phrase rendered in direct, unpretentious language but which come to life by the precision placement often of just a single word. There is a sense of the universal to much of Taylor’s work, a commonality of experience intertwined with immediately recognisable cultural touchstones. She isn’t afraid to mine popular culture for material. I counted at least seven poems in Dressing for the Afterlife that refer to cinema, from the delightful sass and sexiness of ‘I Began the Twenty-Twenties as a Silent Film Goddess’ (“I dined on prosperity sandwiches and sidecars, / leaving restaurants with a sugar-rimmed mouth”) to the matrimonially unfortunate situation of being caught in flagrante with Daniel Craig in ‘Hypothetical’.

A friend of mine asks me if I’d sleep with Daniel Craig.

Before I have time to answer, I’m in bed with Daniel Craig.

He’s stirring out of sleep, smelling of Tobacco Vanille,

he flatters my performance, asks if I’d like coffee.

‘Hang on,’ I say, ‘I did not sleep with you, Daniel Craig,

this is just a conversational frolic.’

These two pieces are fun and sparky, contrasting well with ‘How to Survive a Disaster Movie’ (a stellar example of the list poem done right) and ‘Gangsters’, in which the smoky amoral cityscapes of a George Raft or Humphrey Bogart mob movie explicate the transience of a miner and his family’s life in the Midlands. The narrator states flatly in the poem’s opening “Bassetlaw men always talked coal / behind closed doors, away from kids”, imagining her father and his workmates “in pinstripes / and trilbys … / smoking, playing seven card stud”. As acceptance of the worked-out reality of the pits sets in, the narrator still clings to Hollywood tropes in order to retain some semblance of meaning or anti-hero glamour:

… he drifted from place to place:

Cottam, High Marnham, West Burton,

like bad men in movies,

whistling and coin-flipping in bars,

a tommy-gun in our Cortina’s boot.

The actor Harrison Ford once said in interview that he picked screenplays on the basis of reading the first few pages and then the last; if the protagonist hadn’t changed (i.e. if there was no evidence of a character arc), he would be unlikely to pursue it as a project. Circling back to the poems on running, one can apply Ford’s dictum to Dressing for the Afterlife and the distance travelled between them is palpable. It’s a journey that sees Taylor flexing her muscles as a poet and I’d highly recommend tagging along for the ride.

Neil Fulwood

Nov 13 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Maria Taylor

Poetry review – DRESSING FOR THE AFTERLIFE: Neil Fulwood finds that Maria Taylor’s energetic collection covers a lot of ground

Maria Taylor’s long-awaited new collection is bookended by poems about running. Here are the opening lines of ‘She Ran’:

Aptly, this is an off-the-blocks kind of poem, a poem of movement and energy in which Taylor sprints through a potted autobiography. It fizzes with energy and an exuberant use of language. That wonderful phrase “a filthy jitty” is soon joined by the likes of “I ran past all my exes, even a few crushes / who sipped mochas and wore dark glasses” and “I ran in a wedding dress that scattered confetti / and was cheered by the cast of Star Wars”.

‘Woman Running Alone’ is harder to pull a handy two or three line quote from. It consists of two sentences, the first of which unspools through nineteen lines while the second is left purposefully unfinished. The other reason I’m not going to quote from it is because it deserves to be discovered in precisely the place it occupies: the final page of the collection, where it acts as both a thematic re-encapsulation and, in its refusal to end on a full stop, a continuation of Dressing for the Afterlife’s central theme of movement; a pushing forward to whatever Taylor publishes next.

It’s a lazy critic who takes their prompts from other reviews, but a recent appraisal by Alan Baker on the Litter website is worth mentioning, particularly his identification of “two forces operating; one is pushing the poetry to be the standard poetry of the British mainstream variety … and another pushing it towards something much more interesting, which is unpredictable, language-driven and exciting”.

Therefore the movement that propels Dressing for the Afterlife isn’t just thematic – movement as in physical motion, movement as in geographical displacement/immigration, movement as in the multitasking necessitated by motherhood, movement as in interaction/intertextuality (nimbly and wittily explored in ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’) and movement as in moving pictures – but an integral component of Taylor’s linguistic and poetic capabilities.

There is much, then, to discover, discuss and deconstruct here – which leads me to the part-caveat-part-apology that I’ve thrown out in a couple of previous reviews here on London Grip: that I don’t want to overdo the analysis in favour of preserving the joy of discovery for the reader; that I don’t want to quote too much from the collection, no matter how tempting it is to stud the review with snippets; and that I don’t always want to contextualise the quotes I do use. Such as these:

There are turns of phrase that linger and that you catch the flavour of like a memory surfacing; turns of phrase rendered in direct, unpretentious language but which come to life by the precision placement often of just a single word. There is a sense of the universal to much of Taylor’s work, a commonality of experience intertwined with immediately recognisable cultural touchstones. She isn’t afraid to mine popular culture for material. I counted at least seven poems in Dressing for the Afterlife that refer to cinema, from the delightful sass and sexiness of ‘I Began the Twenty-Twenties as a Silent Film Goddess’ (“I dined on prosperity sandwiches and sidecars, / leaving restaurants with a sugar-rimmed mouth”) to the matrimonially unfortunate situation of being caught in flagrante with Daniel Craig in ‘Hypothetical’.

These two pieces are fun and sparky, contrasting well with ‘How to Survive a Disaster Movie’ (a stellar example of the list poem done right) and ‘Gangsters’, in which the smoky amoral cityscapes of a George Raft or Humphrey Bogart mob movie explicate the transience of a miner and his family’s life in the Midlands. The narrator states flatly in the poem’s opening “Bassetlaw men always talked coal / behind closed doors, away from kids”, imagining her father and his workmates “in pinstripes / and trilbys … / smoking, playing seven card stud”. As acceptance of the worked-out reality of the pits sets in, the narrator still clings to Hollywood tropes in order to retain some semblance of meaning or anti-hero glamour:

The actor Harrison Ford once said in interview that he picked screenplays on the basis of reading the first few pages and then the last; if the protagonist hadn’t changed (i.e. if there was no evidence of a character arc), he would be unlikely to pursue it as a project. Circling back to the poems on running, one can apply Ford’s dictum to Dressing for the Afterlife and the distance travelled between them is palpable. It’s a journey that sees Taylor flexing her muscles as a poet and I’d highly recommend tagging along for the ride.

Neil Fulwood