Poetry review – HOW THE HELL ARE YOU: Michael Bartholomew-Biggs appreciates the highly individual worldview revealed in Glyn Maxwell’s new collection

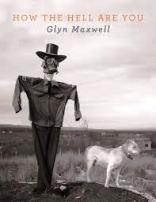

How The Hell Are You

Glyn Maxwell

Picador Poetry

ISBN 9781529037739

66pp £10.99

How The Hell Are You

Glyn Maxwell

Picador Poetry

ISBN 9781529037739

66pp £10.99

In his latest collection, How The Hell Are You, Glyn Maxwell takes appropriate notice of subjects he addresses very seriously in his excellent teaching text On Poetry. Time (sometimes accorded a capital T) and the blank white page (and its relationship to black type) figure in many of the poems. For the blank page we have to wait till page 27, but time crops up in the very first poem “The Strain” which warns us that anything that has wanted ‘to be young forever’ has always had to face the truth that ‘the snag to this was time, time needed / taking out. ‘

A less aggressive approach to time occurs in “Daylight Saving” (an elegy for the poet’s father) which tells us ‘they are considering doing away / with daylight saving’ and observes

... whatever they save

they will lose as they do, it’s not going to be Time,

who knows why they had daylight saving at all?

I’m just glad we had it.

A more ominously enigmatic reference to time comes in “Advice To The Players” – evidently directed to the cast of a production of Hamlet. The poem offers the repeated injunction ‘don’t play the ending’ because to do so would involve having to

... say the words

the dead have picked for Time

to learn by rote.

These lines suggest that the players (and perhaps the reader too) do not fully understand the enormity of what they are engaged in. Other poems in the collection also explore this experience of being less in command of a situation than one supposes. “Blank Page Speaks” questions whether a poet really has total control of the tools of composition. The empty page uses sardonic and patronising tones to greet the poet’s appearance first thing in the morning ‘in a ragged gown to do your business’ – the business being

to pen your variation on a theme of

how you are

this morning. May I say I had a dream of

something too?

Obviously not and off you go now.

Left your little footprint let it snow now

let it snow

(While we are here, I will note the small neat rhymes ‘theme of/dream of’ and ‘go now /snow now’. Maxwell makes frequent and effective use of rhyme in this collection in ways that are often unobtrusive and rarely fall with the heavy thump of a dreaded second shoe.)

Now back to the blank page which – not content with merely sniping at the poet –goes on to lay some claim to a frustrated creativity of its own

May I say that when you’re gone

I get to work.

I got to work

just then. Back then

the second you were done,

[“Blank Page Gets To Work”]

The idea of the page having a degree of independence and possibly meddling with the poet’s efforts is carried a stage further in “The White”

And now it dawns on you

you’re in a fight with something: what you make

is making something too,

and it’s something you don’t mean ....

If a page can rebel against the supposed authority of the writer then what else might prove unexpectedly recalcitrant? Perhaps poems have opinions too – like those expressed in “One Gone Rogue” which begins with the claim that ’No one made me, nothing did.’ and continues

I’m no one’s. Clock me and I clock the fuck

right back at you I’ve never been begun.

I was never worked on why would I take work

and who would do it?

Other poems in the book also fail to “know their place” and give their own, usually contrary, views. Maxwell too is prepared to set aside conventional relationships between poet and reader by doing something akin to breaking the fourth wall in a theatre. For instance, in “The Light You Saw” he confides ‘This poem ends, you can see if you dip your eye. / Dip it and lift it again and be here with me.’

Self-opinionated poems are one thing, but a more far-reaching and sinister rebellion seems to be brewing in three poems about Artificial Intelligence (AI) progressively slipping out of humanity’s control until it declares

The bloody wants to we don’t have to do

a thing the bloody wants there’ll always be

a thing the bloody wants and we mean you.

There is more in these AI poems than rebellion however. They remind us that, while humanity has prided itself on exploiting AI, AI has (presumably) had a chance to learn from its observations of humanity and to detect an increasing tendency prefer black and white categories to the gentler nuances of ‘maybe and let live and who in heaven / knows’

It has not gone unnoticed by AI.

That you think This or That of things i.e.

‘if this is yes then that is no’ and ‘if

this is no then that is yes’

it has not

gone unnoticed. No it has gone noticed.

[“Song of AI”]

AI’s further deductions and their consequences are outlined in the rest of the poem and they are not pretty.

What has surely gone noticed in the extracts quoted already is Maxwell’s use of echoed or closely-repeated words. This often produces sentences that seem to fold and re-fold upon themselves so that subsequent clauses clarify or qualify or even contradict the opening. A good example is in “Plainsong Of The Undiscovered” (which I find to be one of the book’s most thought-provoking poems). The opening stanzas need to be quoted at some length to illustrate the point:

You who go in search

with a lantern and a staff

in the dark that you consider

to be dark that wishes only

to be scattered by your lantern

may we ask you to remember you are

visible for miles

have been visible to us

from the dark that you consider

to be dark we are observing

the decisions of your lantern

Is it fanciful to think the subtle shifts of viewpoint and of emphasis are matched by the way occasional indented lines give the impression of the poem shaking its head and re-focussing?

The layered phrases in “Plainsong Of The Undiscovered” ask to be read quite slowly and deliberately; but elsewhere words pour down in a more helter-skelter fashion. In the book’s title poem we have

How the hell am I?

Barely know these days my friend

we get by we get by

but the nights are good I don’t know why

I do know why enough of this don’t

oh my man don’t cry.

I find these unguarded and tumbled-out words quite moving. The poem seems to capture both the boisterous incoherence and the suppressed pathos that characterises much present day public discourse. “How The Hell Are You?” is presented as a (stylised) conversation – but much of the rest of the book also has a conversational tone to it and mostly uses everyday language. Since Maxwell is a dramatist as well as a poet he is very good at making speech sound “natural” even when it is much more artfully constructed than real-life dialogue can hope to be.

There is much more to admire in the collection and two longer poems deserve particular mention. “Thirty Years” is a delicate tribute to Derek Walcott both as fine poet and as teacher (‘…the wince is yours / when the line-break’s wrong …’). “Pasolini’s Satan” is based on the film version of The Gospel According to St Matthew and is an intriguing re-imagining of the wilderness confrontation between Jesus and the Devil in which Satan puts on his ‘dead banana black shoes’ in order to tread the desert’s ‘hideous fahrenheit’.

Almost inevitably in any collection there are a handful of poems which don’t seem to me to match up to the subtlety and inventiveness of the rest. Perhaps these were so successful at being deceptively simple that they deceived me into dismissing them too readily. But this is a very small negative remark and I can say for sure that How The Hell Are You is a book I have compulsively kept re-opening and re-reading. And I have found fresh pleasures every time.

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

Nov 14 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Glyn Maxwell

Poetry review – HOW THE HELL ARE YOU: Michael Bartholomew-Biggs appreciates the highly individual worldview revealed in Glyn Maxwell’s new collection

In his latest collection, How The Hell Are You, Glyn Maxwell takes appropriate notice of subjects he addresses very seriously in his excellent teaching text On Poetry. Time (sometimes accorded a capital T) and the blank white page (and its relationship to black type) figure in many of the poems. For the blank page we have to wait till page 27, but time crops up in the very first poem “The Strain” which warns us that anything that has wanted ‘to be young forever’ has always had to face the truth that ‘the snag to this was time, time needed / taking out. ‘

A less aggressive approach to time occurs in “Daylight Saving” (an elegy for the poet’s father) which tells us ‘they are considering doing away / with daylight saving’ and observes

... whatever they save they will lose as they do, it’s not going to be Time, who knows why they had daylight saving at all? I’m just glad we had it.A more ominously enigmatic reference to time comes in “Advice To The Players” – evidently directed to the cast of a production of Hamlet. The poem offers the repeated injunction ‘don’t play the ending’ because to do so would involve having to

... say the words the dead have picked for Time to learn by rote.These lines suggest that the players (and perhaps the reader too) do not fully understand the enormity of what they are engaged in. Other poems in the collection also explore this experience of being less in command of a situation than one supposes. “Blank Page Speaks” questions whether a poet really has total control of the tools of composition. The empty page uses sardonic and patronising tones to greet the poet’s appearance first thing in the morning ‘in a ragged gown to do your business’ – the business being

to pen your variation on a theme of how you are this morning. May I say I had a dream of something too? Obviously not and off you go now. Left your little footprint let it snow now let it snow(While we are here, I will note the small neat rhymes ‘theme of/dream of’ and ‘go now /snow now’. Maxwell makes frequent and effective use of rhyme in this collection in ways that are often unobtrusive and rarely fall with the heavy thump of a dreaded second shoe.)

Now back to the blank page which – not content with merely sniping at the poet –goes on to lay some claim to a frustrated creativity of its own

May I say that when you’re gone I get to work. I got to work just then. Back then the second you were done, [“Blank Page Gets To Work”]The idea of the page having a degree of independence and possibly meddling with the poet’s efforts is carried a stage further in “The White”

If a page can rebel against the supposed authority of the writer then what else might prove unexpectedly recalcitrant? Perhaps poems have opinions too – like those expressed in “One Gone Rogue” which begins with the claim that ’No one made me, nothing did.’ and continues

Other poems in the book also fail to “know their place” and give their own, usually contrary, views. Maxwell too is prepared to set aside conventional relationships between poet and reader by doing something akin to breaking the fourth wall in a theatre. For instance, in “The Light You Saw” he confides ‘This poem ends, you can see if you dip your eye. / Dip it and lift it again and be here with me.’

Self-opinionated poems are one thing, but a more far-reaching and sinister rebellion seems to be brewing in three poems about Artificial Intelligence (AI) progressively slipping out of humanity’s control until it declares

There is more in these AI poems than rebellion however. They remind us that, while humanity has prided itself on exploiting AI, AI has (presumably) had a chance to learn from its observations of humanity and to detect an increasing tendency prefer black and white categories to the gentler nuances of ‘maybe and let live and who in heaven / knows’

It has not gone unnoticed by AI. That you think This or That of things i.e. ‘if this is yes then that is no’ and ‘if this is no then that is yes’ it has not gone unnoticed. No it has gone noticed. [“Song of AI”]AI’s further deductions and their consequences are outlined in the rest of the poem and they are not pretty.

What has surely gone noticed in the extracts quoted already is Maxwell’s use of echoed or closely-repeated words. This often produces sentences that seem to fold and re-fold upon themselves so that subsequent clauses clarify or qualify or even contradict the opening. A good example is in “Plainsong Of The Undiscovered” (which I find to be one of the book’s most thought-provoking poems). The opening stanzas need to be quoted at some length to illustrate the point:

You who go in search with a lantern and a staff in the dark that you consider to be dark that wishes only to be scattered by your lantern may we ask you to remember you are visible for miles have been visible to us from the dark that you consider to be dark we are observing the decisions of your lanternIs it fanciful to think the subtle shifts of viewpoint and of emphasis are matched by the way occasional indented lines give the impression of the poem shaking its head and re-focussing?

The layered phrases in “Plainsong Of The Undiscovered” ask to be read quite slowly and deliberately; but elsewhere words pour down in a more helter-skelter fashion. In the book’s title poem we have

I find these unguarded and tumbled-out words quite moving. The poem seems to capture both the boisterous incoherence and the suppressed pathos that characterises much present day public discourse. “How The Hell Are You?” is presented as a (stylised) conversation – but much of the rest of the book also has a conversational tone to it and mostly uses everyday language. Since Maxwell is a dramatist as well as a poet he is very good at making speech sound “natural” even when it is much more artfully constructed than real-life dialogue can hope to be.

There is much more to admire in the collection and two longer poems deserve particular mention. “Thirty Years” is a delicate tribute to Derek Walcott both as fine poet and as teacher (‘…the wince is yours / when the line-break’s wrong …’). “Pasolini’s Satan” is based on the film version of The Gospel According to St Matthew and is an intriguing re-imagining of the wilderness confrontation between Jesus and the Devil in which Satan puts on his ‘dead banana black shoes’ in order to tread the desert’s ‘hideous fahrenheit’.

Almost inevitably in any collection there are a handful of poems which don’t seem to me to match up to the subtlety and inventiveness of the rest. Perhaps these were so successful at being deceptively simple that they deceived me into dismissing them too readily. But this is a very small negative remark and I can say for sure that How The Hell Are You is a book I have compulsively kept re-opening and re-reading. And I have found fresh pleasures every time.

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs