Poetry review – FIRST HARE: Mat Riches explores the principles behind Richie McCaffery‘s poetry

First Hare

Richie McCaffery

Mariscat Press

ISBN 978 1 9160609 5 1

£6

First Hare

Richie McCaffery

Mariscat Press

ISBN 978 1 9160609 5 1

£6

Richie McCaffery is a prolific poet. First Hare his third pamphlet in eight years, during which he has produced two full collections; but it would appear that the quality isn’t diminishing. Over half of the poems in this pamphlet have been published in magazines and journals, both in print and online. All of this suggests someone who has learned enough to know what they are doing.

In ‘Growing a beard’ toward the end of the pamphlet we’re told

For now I’m going to hide behind a beard

that makes my face look like a scrap of paper

someone’s tried out old biros on.

Enough sketchiness to make people

think there’s a grand plan taking shape.

The structuring of First Hare suggests that he, McCaffery, does have a grand plan. The poem that opens the pamphlet, “Northumbrian”, is made of three distinct sections, with each section performing the classic McCaffery-ian move of making a wider point, of looking at the bigger picture before homing in on the personal, the local or the specific to make the core point he wants to get across. It’s something he has done very well throughout his work since his first pamphlet and collection, Spinning Plates and Cairn, respectively.

However, “Northumbrian” is worth concentrating on a little more, because it performs a couple of valuable services. Firstly, it gives the book its title, but more importantly, I think it manages to set out the book’s three key themes: time and growth; what we learn from others; and what we do to protect others. Let’s look at each theme in turn.

The first section describes a Northumbrian drystone wall and an uncertainty around the boundaries, but it’s the second stanza that addresses that first theme of time and growth, likening the accretion of knowledge and experience to the development of lichen on rocks.

I want us to be like one of these walls—

nothing between us, no mortar or cement,

slotted in perfectly together, lichens

awarded us like rosettes.

Elsewhere, in “Le Merle Blanc”, McCaffery talks about an old fountain pen he uses to write with that belonged to his Belgian partner’s grandfather, describing it as

a gift for his first Holy Communion

and then for me, seven decades later

Silenced by the war, its bladder burst,

holding in unwritten secrets.

Repaired, it writes in English now.

However, these distances back in time are nothing compared to the shift in geological time we see in “Sea-coal”, where the poet reflects on life and time, putting life in the context of the long term.

The poem starts with McCaffery essentially noting that he didn’t ask to come into this world, ‘The TV’s been telling me yet again / I need to make preparations for my death. / I made none for my birth.’ By the time (that word again) we get to the end of the poem we’ve reached back to an entirely different place in history.

We protest against it like sea-coal,

scavenged during a cold snap,

spitting on a beachcombed fire,

wave-worn but still burning.

Both the sea-coal and the poet have been formed, perhaps against their wishes, by their environment and time. It remains to be seen whether the poet is as powerless against the world as the coal is.. The coal can’t write poems.

Section two of “Northumbrian” looks at the impact of home, of land being sold off and focusses on the poet and his partner.

We move so much I sometimes

think we’re stolen goods.

I helped you spot your first hare.

This fact seems important now.

Regardless of why this is important, it is important to them; and these things that we pass on to our loved ones feature throughout the book. Examples range from McCaffery passing on encouragement to a young nephew ‘having a tough time at school’ in ‘Uncles’ to the way what we pass on to our relations deepens like Larkin’s ‘coastal shelf’ in “Falling”. His great-grandfather ‘came from felling and spent his life falling’. Once, from a tree during WW1, ‘Shot in the shoulder before he could take aim’ and, ‘Later in a riveter’s brace on the Tyne, he plummeted into the bowels of a liner.’ This is emphasised by the lines

They put him somewhere he could fall no more

but he’d already laced his gene pool

with a desire for descent…

The poem goes on to suggest the poet’s initial unease at this family gene pool, but as with “Sea coal”, there’s a sense of accepting the circumstances that the end of the poem.

...It used to scare me

but now I like the sense of weightlessness,

of being unburdened.

The final section of “Northumbrian” sees the poet protecting his wife’s innocence when she asks about pheasant feeders seen out in the fields near their home.

You told me: That’s so kind!

I hadn’t the heart to tell you the truth

and kill your desire to see good

always in the midst of bad.

We can see this instinct, whether it is the right thing to do or not, in other poems. For example, in “Sports days” we’re told that his mother had been a ‘guitar tech for world-famous bands’ but had given it up to clean a school when ‘Dad lost his job at the coal board.’. She ‘worked two jobs and raised two of us.’ It is however unclear whether this refers to McCaffery and his Dad, or if there’s a sibling involved; but I’m assuming the later given the presence of a sister in other poems. However, his mother’s sacrifices are mimicked by McCaffery’s actions later in the poem.

On mandatory sports days I always took pride

in taking my time and if someone fell down,

bloodied their knee I’d stop to help them back up.

She’d be there, cheering me on as I came last.

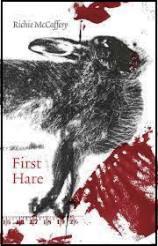

The cover of this collection, a print by the artist Brent Millar, accurately shows us some of what is to come inside the book: a delicate looking, but actually robust creature is laid out, measured up for size and set against time. Actually, that about sums it up. The pamphlet cover is its own review of the book.

Mat Riches

Oct 17 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Richie McCaffery

Poetry review – FIRST HARE: Mat Riches explores the principles behind Richie McCaffery‘s poetry

Richie McCaffery is a prolific poet. First Hare his third pamphlet in eight years, during which he has produced two full collections; but it would appear that the quality isn’t diminishing. Over half of the poems in this pamphlet have been published in magazines and journals, both in print and online. All of this suggests someone who has learned enough to know what they are doing.

In ‘Growing a beard’ toward the end of the pamphlet we’re told

The structuring of First Hare suggests that he, McCaffery, does have a grand plan. The poem that opens the pamphlet, “Northumbrian”, is made of three distinct sections, with each section performing the classic McCaffery-ian move of making a wider point, of looking at the bigger picture before homing in on the personal, the local or the specific to make the core point he wants to get across. It’s something he has done very well throughout his work since his first pamphlet and collection, Spinning Plates and Cairn, respectively.

However, “Northumbrian” is worth concentrating on a little more, because it performs a couple of valuable services. Firstly, it gives the book its title, but more importantly, I think it manages to set out the book’s three key themes: time and growth; what we learn from others; and what we do to protect others. Let’s look at each theme in turn.

The first section describes a Northumbrian drystone wall and an uncertainty around the boundaries, but it’s the second stanza that addresses that first theme of time and growth, likening the accretion of knowledge and experience to the development of lichen on rocks.

Elsewhere, in “Le Merle Blanc”, McCaffery talks about an old fountain pen he uses to write with that belonged to his Belgian partner’s grandfather, describing it as

However, these distances back in time are nothing compared to the shift in geological time we see in “Sea-coal”, where the poet reflects on life and time, putting life in the context of the long term.

The poem starts with McCaffery essentially noting that he didn’t ask to come into this world, ‘The TV’s been telling me yet again / I need to make preparations for my death. / I made none for my birth.’ By the time (that word again) we get to the end of the poem we’ve reached back to an entirely different place in history.

Both the sea-coal and the poet have been formed, perhaps against their wishes, by their environment and time. It remains to be seen whether the poet is as powerless against the world as the coal is.. The coal can’t write poems.

Section two of “Northumbrian” looks at the impact of home, of land being sold off and focusses on the poet and his partner.

Regardless of why this is important, it is important to them; and these things that we pass on to our loved ones feature throughout the book. Examples range from McCaffery passing on encouragement to a young nephew ‘having a tough time at school’ in ‘Uncles’ to the way what we pass on to our relations deepens like Larkin’s ‘coastal shelf’ in “Falling”. His great-grandfather ‘came from felling and spent his life falling’. Once, from a tree during WW1, ‘Shot in the shoulder before he could take aim’ and, ‘Later in a riveter’s brace on the Tyne, he plummeted into the bowels of a liner.’ This is emphasised by the lines

The poem goes on to suggest the poet’s initial unease at this family gene pool, but as with “Sea coal”, there’s a sense of accepting the circumstances that the end of the poem.

The final section of “Northumbrian” sees the poet protecting his wife’s innocence when she asks about pheasant feeders seen out in the fields near their home.

We can see this instinct, whether it is the right thing to do or not, in other poems. For example, in “Sports days” we’re told that his mother had been a ‘guitar tech for world-famous bands’ but had given it up to clean a school when ‘Dad lost his job at the coal board.’. She ‘worked two jobs and raised two of us.’ It is however unclear whether this refers to McCaffery and his Dad, or if there’s a sibling involved; but I’m assuming the later given the presence of a sister in other poems. However, his mother’s sacrifices are mimicked by McCaffery’s actions later in the poem.

The cover of this collection, a print by the artist Brent Millar, accurately shows us some of what is to come inside the book: a delicate looking, but actually robust creature is laid out, measured up for size and set against time. Actually, that about sums it up. The pamphlet cover is its own review of the book.

Mat Riches