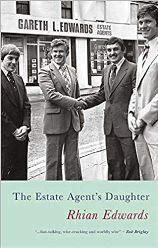

Poetry review – THE ESTATE AGENT’S DAUGHTER: Mat Riches welcomes a well-presented and characterful new collection from Rhian Edwards

he Estate Agent’s Daughter

Rhian Edwards

Seren

ISBN 978-1781725832

£9.99

he Estate Agent’s Daughter

Rhian Edwards

Seren

ISBN 978-1781725832

£9.99

How long is too long when you’re waiting, relatively patiently, for a follow-up collection from a poet? It’s been eight years since Rhian Edwards’ debut collection, Clueless Dogs, and three since her pamphlet, Brood—some of which is included in her new collection, The Estate Agent’s Daughter. However, while it appears to have been a rough eight years for Edwards – or at the very least for Edwards’ characters – it has been eight years well spent.

This by rights should be the collection that sees Edwards move up a gear and into a different league. And in many ways, she’s achieved this step forward by looking backwards, by ratcheting the catapult back a notch to let go and fly. In some ways this at its most clear in, “Poems in the Dock”, where

Her poems have been subpoenaed, summonsed

by the ex-husband to give witness testimony

against the mental health of their author.

Work from Clueless Dog is mentioned throughout the poem including ‘Gravy, Suitcase and Marital Visit’ who are ‘called as a cluster / to substantiate the poet’s diminished moral character.’ However, the real movement comes from taking stock, and that starts in the titular poem at the beginning of the collection, albeit in a slightly surreal way, with Edwards describing herself in the style of an estate agent. She ‘is sold as seen, / semi-detached’ and her

Ground floor comprises open plan lounge / diner,

recesses either side of fire breast wall.

Her writing desk has been nudged to the brink

of the bay. Curtains may be drawn

around her to quarantine at will.

That word ‘quarantine’ takes on a slightly different hue at present, but the writing desk nudged back, the curtains drawn round, the ‘sold as seen’ all suggest someone getting on with the act of living, but also someone who has become comfortable in their own skin in a take-me-as-I-am kind of way.

What follows this poem is a look back at the estate agent of the title, Edwards’ dad and time spent accompanying him to work. In “Counting Boards”, ‘Instead of I-spy in your Cortina, / we counted your For Sale boards’. Her dad dispenses knowledge as part of the day and her education— ‘You taught me ratios by five-bar gating / the boards of your competitors’. While the clues are there throughout the poem in the use of adjectives like ‘petrified’, ‘crowbarred’, ‘loathed’ and ‘groomed’, it is the last lines that truly pull the reader up short.

You confided more words to your dictaphone

than I could receive in a single tax year.

The rest of the first section covers a marriage and its dissolution along with the arrival of a child. Poems from Edwards’ pamphlet, Brood, are included here with slightly altered titles, and in some places some minor reworkings. For example, what was called “6. Gold” in the pamphlet is now “White Gold (Six For A Wish) in the collection, and a stanza that read

All that morning in the woods,

I had been rehearsing a way

to finally put an end to us.

now reads

All morning, I had been rehearsing

a way to finally

put an end to us

The two weak line endings of the first version replaced by three and the new emphases on ‘finally’ and ‘put’ make for a stronger version. Aside from writing other poems for the collection, the three years since Brood have not been wasted with idle tinkering.

The ‘finally put(ting) an end to us’ is instructive. There are further examples of a marriage that didn’t start or continue on the right foot. In “Argos Wedding” a joyous and potentially romantic occasion has exactly none of either in it. The almost transactional nature of the procedure is ‘akin to the wait / at Alton Towers.’ And ‘I am the only thing here / that belongs to me’. The poem ends with Edwards looking at a broken compact mirror, being watched by the brides to follow her ‘as if I have cursed this conveyor belt / of non-committal brides.’

There are further clues as to the dissolution of a marriage in “The Birds of Rhiannnon”, with the protagonist’s use of the phrases, ‘For the sake of this world and him’ and later in the second stanza ‘For the sake of my world and him, / I crowded my belly with children.’

The first section ends an updating of the “Blodeuwedd myth” where a woman made of flowers is now described as a ‘primeval catalogue bride’. Is this a throwback to the earlier “Argos Wedding”? Probably no, but you have to admire the sequencing. While I have to confess to not always being 100% certain what the poem is saying, I am 100% in love with the sound of it and the consonance of it. A prime example of this is the third stanza; it’s positively dripping with ems, esses and tees.

My meadowsweet, mead wort,

bride wort, grows in dampness.

I am strewing herb

to scent your floors. I almond

you stewed fruit. I am tea

for your gout and fever,

aspirin for your acid gut.

Section two of the collection covers a great deal of ground and largely deals with identity and characters and/or places that you would assume loom large in the poet’s life. Indeed, the first poem of this section may even be identifying what makes a life. “It Is” seems like a perfectly lovely poem pointing out lots of what makes life worth living.

The revelation of the runny yolk

after the egg has been scalped

[…]

The fluent descent of the coffee plunger;

the smell of toast, the unrivalled char of it;

the unearthing of a mix tape from your first love;

the relief of a decent barrister against your ex

[…]

The twelve-week scan that testifies

to proof of life.

The poem is fine and dandy, pointing out lots of lovely life-affirming things, but it’s the turn after the ‘mix tape’ that makes it for me with the insertion of some bitterness, some sense of the eggshell in the boiled egg with the introduction of divorce proceedings. There would be nothing wrong with the poem without that note, but it is all the better for adding that balance.

As mentioned earlier, Edwards even treats her own poems as characters, and indeed as character witnesses in the poem, ”Poem in the Dock”. But we also see a knick-knack drawer, pain, a couple called Enid and David Hughes, a wooden bench, a cinema; and Edwards’ own parents Kay and Gareth make an appearance.

After the harrowing first section and the intensely personal nature of much, if not all, of it, it’s entirely understandable to want to get some distance from that by writing about others. But there are poems that pull the reader/Edwards back close to her own world. In “Kay”, about her mother, we open with ‘She sits before the boiler, / guarding its pulse, / warming her back’ and this feels like a shout back to “The Hatching” in Clueless Dogs and its opening lines of ‘Born in the airing cupboard / to the mothering pulse of the boiler’.

While, in “Kay” we see the poem being complementary—‘Jeans flatter her dancers’ legs’— in “Gareth”, which I read as being about her father, there is still some pretty personal stuff going on, and Gareth, whoever he is, doesn’t come out of this smelling of roses. The first stanza harks back to the person in “Counting Boards” with the lines, ‘A blood crescent moon / capsized on its side, / cradles a yellowing eye. / It weeps of its own accord. It would not cry otherwise’. That feeling of silence, of holding things in is powerful stuff. However, the kicker is to come at the end. The poetry wrestled from such a grim act is exquisite stuff and reminds me of a more disgusting version of Yeats’ lace on a Guinness glass.

He hawks and gobs through

the open car window.

The wind reciprocates the gift,

splattering his face

with a bridal veil

of his own embroidery.

There’s a strong argument that this second section, and indeed much of the collection, is thematically about transformation and change. Moving from life to death is present in the poems about Enid and David, the change in her father in “Gareth”, the transformation of “The Birds of Rhiannon” (‘Before I was mortal, I was haloed / in feathers…’). But this transformation is there for Edwards too. In “I Am Turning” we see her becoming a domestic “goddess” (to use a horrible phrase), but someone that also gathers confidence and courage from this change.

I am in raptures over the new pedal bin.

How it sits perfectly in the silver

between the backdoor and the drier.

[…]

I am the conscientious dietician, who ensures

three fruits in her daughter’s breakfast,

four vegetables smuggled into dinner.

[…]

After all of the preceding lines about tidiness and care for her child, and despite the repeated ‘I’, she manages to sneak in a reference to herself.

I am the diligent creator, who prints,

dates and names every person in every photo

of her daughter’s life, even naming myself.

Is that the act of someone giving it the big I am, or the act of someone who feels they won’t be remembered or recognised?

The theme of change continues in the third and final section of the collection which explores what I take to be a series of relationships. In “Thinner” we’re told he ‘…panicked off my pounds, spry / under house arrest, my fat absconded / under the audit of a perishing husband.’ Again, reaching back to Clueless Dogs this poem is like the opposite of “The Unkindness”, ‘Where the lithe / has melted into a cosy body’. This new person has ‘chased away [their] your stones, marathon / miles at a time, pedalled them up mountains, / dissolved them in breast strokes.’

However, despite previously dismissing this person as a potential lover or partner, eventually they ‘fill the bed with our foreign bodies, / our stomachs groaning, see-sawing / on the pebbles of each other’s hipbones’. The references to ‘foreign bodies’ and things that don’t belong, the un-satiated stomachs and the reduction to bones all suggest that this is a relationship that won’t last, that it’s a transitional thing for someone who is changing.

The character(s) keep coming in this section, and we learn much about them, for example in “He Is The Kind”, where we meet a man who, while appearing learned, quoting the paediatrician and psychologist ‘Winnicott while stirring honey into his porridge’ is also ‘the kind of man who brings / two mugs of tea to bed in the morning, / both of which are for himself.’ Who would stay with such a monster?

While we meet these new characters, we continue to build on themes from earlier in the book. For example, we learned about the shift to domesticity and order in “I Am Turning”, and this comes out again in “He Is The Kind”, where he is the kind of man that ‘discards teabags on the draining board, / despite my navigations to the compost bin’. In “In A Relationship (Pending)” the opening poem’s theme of exploration of the self as an estate agent’s guide is repeated/reprised.

Now I have said it, I pedal

frantically towards a future.

Although the survey declares (us)

structurally unsound,

in need of underpinning.

However, towards the back end of the collection, we see things moving towards a happier ending (for now?). In “Fatter”, echoing “Thinner” from earlier, we see the poet declaring she has returned to her ‘fighting weight’ and after this man admits he preferred her ‘heroin chic of when we first met’ we see Edwards realising this is over…

I deemed you too slight for loving then,

knowing there was too much of me,

even when there was nothing of me

The collection ends with of the ‘tranquilizing voice’ of “The Addiction Counsellor”. I was a little confused as to the proprietary nature of the relationship. While she edges ‘closer than fiduciary allows’, ‘He holds my hipbones / lightly as he passes me in the doorway.’

Perhaps it’s transference that causes this excitement, someone being kind is misinterpreted as being something else after the excuses for men that came before. However, it’s telling that it’s Edwards’ daughter that forms the voice of reason at the end. ‘She rightly reprimands / me for wolfing butterflies again.’ That note of caution is a wise one.

Estate agents are experts at shifting your perspective when they want to sell a house, taking photos at odd angles to make a house appear bigger, often somehow shifting a postcode to appear in a more desirable area or making a feature of the bus route that runs outside the house (Near to public transport…). I don’t know how good Rhian Edwards is as an estate agent, but she’s certainly learnt the tricks of shifting perspectives and making us look again at places and events we may have overlooked. I hope it’s not another eight years before we see a new collection.

Mat Riches

Oct 1 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Rhian Edwards

Poetry review – THE ESTATE AGENT’S DAUGHTER: Mat Riches welcomes a well-presented and characterful new collection from Rhian Edwards

How long is too long when you’re waiting, relatively patiently, for a follow-up collection from a poet? It’s been eight years since Rhian Edwards’ debut collection, Clueless Dogs, and three since her pamphlet, Brood—some of which is included in her new collection, The Estate Agent’s Daughter. However, while it appears to have been a rough eight years for Edwards – or at the very least for Edwards’ characters – it has been eight years well spent.

This by rights should be the collection that sees Edwards move up a gear and into a different league. And in many ways, she’s achieved this step forward by looking backwards, by ratcheting the catapult back a notch to let go and fly. In some ways this at its most clear in, “Poems in the Dock”, where

Work from Clueless Dog is mentioned throughout the poem including ‘Gravy, Suitcase and Marital Visit’ who are ‘called as a cluster / to substantiate the poet’s diminished moral character.’ However, the real movement comes from taking stock, and that starts in the titular poem at the beginning of the collection, albeit in a slightly surreal way, with Edwards describing herself in the style of an estate agent. She ‘is sold as seen, / semi-detached’ and her

That word ‘quarantine’ takes on a slightly different hue at present, but the writing desk nudged back, the curtains drawn round, the ‘sold as seen’ all suggest someone getting on with the act of living, but also someone who has become comfortable in their own skin in a take-me-as-I-am kind of way.

What follows this poem is a look back at the estate agent of the title, Edwards’ dad and time spent accompanying him to work. In “Counting Boards”, ‘Instead of I-spy in your Cortina, / we counted your For Sale boards’. Her dad dispenses knowledge as part of the day and her education— ‘You taught me ratios by five-bar gating / the boards of your competitors’. While the clues are there throughout the poem in the use of adjectives like ‘petrified’, ‘crowbarred’, ‘loathed’ and ‘groomed’, it is the last lines that truly pull the reader up short.

The rest of the first section covers a marriage and its dissolution along with the arrival of a child. Poems from Edwards’ pamphlet, Brood, are included here with slightly altered titles, and in some places some minor reworkings. For example, what was called “6. Gold” in the pamphlet is now “White Gold (Six For A Wish) in the collection, and a stanza that read

now reads

The two weak line endings of the first version replaced by three and the new emphases on ‘finally’ and ‘put’ make for a stronger version. Aside from writing other poems for the collection, the three years since Brood have not been wasted with idle tinkering.

The ‘finally put(ting) an end to us’ is instructive. There are further examples of a marriage that didn’t start or continue on the right foot. In “Argos Wedding” a joyous and potentially romantic occasion has exactly none of either in it. The almost transactional nature of the procedure is ‘akin to the wait / at Alton Towers.’ And ‘I am the only thing here / that belongs to me’. The poem ends with Edwards looking at a broken compact mirror, being watched by the brides to follow her ‘as if I have cursed this conveyor belt / of non-committal brides.’

There are further clues as to the dissolution of a marriage in “The Birds of Rhiannnon”, with the protagonist’s use of the phrases, ‘For the sake of this world and him’ and later in the second stanza ‘For the sake of my world and him, / I crowded my belly with children.’

The first section ends an updating of the “Blodeuwedd myth” where a woman made of flowers is now described as a ‘primeval catalogue bride’. Is this a throwback to the earlier “Argos Wedding”? Probably no, but you have to admire the sequencing. While I have to confess to not always being 100% certain what the poem is saying, I am 100% in love with the sound of it and the consonance of it. A prime example of this is the third stanza; it’s positively dripping with ems, esses and tees.

Section two of the collection covers a great deal of ground and largely deals with identity and characters and/or places that you would assume loom large in the poet’s life. Indeed, the first poem of this section may even be identifying what makes a life. “It Is” seems like a perfectly lovely poem pointing out lots of what makes life worth living.

The poem is fine and dandy, pointing out lots of lovely life-affirming things, but it’s the turn after the ‘mix tape’ that makes it for me with the insertion of some bitterness, some sense of the eggshell in the boiled egg with the introduction of divorce proceedings. There would be nothing wrong with the poem without that note, but it is all the better for adding that balance.

As mentioned earlier, Edwards even treats her own poems as characters, and indeed as character witnesses in the poem, ”Poem in the Dock”. But we also see a knick-knack drawer, pain, a couple called Enid and David Hughes, a wooden bench, a cinema; and Edwards’ own parents Kay and Gareth make an appearance.

After the harrowing first section and the intensely personal nature of much, if not all, of it, it’s entirely understandable to want to get some distance from that by writing about others. But there are poems that pull the reader/Edwards back close to her own world. In “Kay”, about her mother, we open with ‘She sits before the boiler, / guarding its pulse, / warming her back’ and this feels like a shout back to “The Hatching” in Clueless Dogs and its opening lines of ‘Born in the airing cupboard / to the mothering pulse of the boiler’.

While, in “Kay” we see the poem being complementary—‘Jeans flatter her dancers’ legs’— in “Gareth”, which I read as being about her father, there is still some pretty personal stuff going on, and Gareth, whoever he is, doesn’t come out of this smelling of roses. The first stanza harks back to the person in “Counting Boards” with the lines, ‘A blood crescent moon / capsized on its side, / cradles a yellowing eye. / It weeps of its own accord. It would not cry otherwise’. That feeling of silence, of holding things in is powerful stuff. However, the kicker is to come at the end. The poetry wrestled from such a grim act is exquisite stuff and reminds me of a more disgusting version of Yeats’ lace on a Guinness glass.

There’s a strong argument that this second section, and indeed much of the collection, is thematically about transformation and change. Moving from life to death is present in the poems about Enid and David, the change in her father in “Gareth”, the transformation of “The Birds of Rhiannon” (‘Before I was mortal, I was haloed / in feathers…’). But this transformation is there for Edwards too. In “I Am Turning” we see her becoming a domestic “goddess” (to use a horrible phrase), but someone that also gathers confidence and courage from this change.

After all of the preceding lines about tidiness and care for her child, and despite the repeated ‘I’, she manages to sneak in a reference to herself.

Is that the act of someone giving it the big I am, or the act of someone who feels they won’t be remembered or recognised?

The theme of change continues in the third and final section of the collection which explores what I take to be a series of relationships. In “Thinner” we’re told he ‘…panicked off my pounds, spry / under house arrest, my fat absconded / under the audit of a perishing husband.’ Again, reaching back to Clueless Dogs this poem is like the opposite of “The Unkindness”, ‘Where the lithe / has melted into a cosy body’. This new person has ‘chased away [their] your stones, marathon / miles at a time, pedalled them up mountains, / dissolved them in breast strokes.’

However, despite previously dismissing this person as a potential lover or partner, eventually they ‘fill the bed with our foreign bodies, / our stomachs groaning, see-sawing / on the pebbles of each other’s hipbones’. The references to ‘foreign bodies’ and things that don’t belong, the un-satiated stomachs and the reduction to bones all suggest that this is a relationship that won’t last, that it’s a transitional thing for someone who is changing.

The character(s) keep coming in this section, and we learn much about them, for example in “He Is The Kind”, where we meet a man who, while appearing learned, quoting the paediatrician and psychologist ‘Winnicott while stirring honey into his porridge’ is also ‘the kind of man who brings / two mugs of tea to bed in the morning, / both of which are for himself.’ Who would stay with such a monster?

While we meet these new characters, we continue to build on themes from earlier in the book. For example, we learned about the shift to domesticity and order in “I Am Turning”, and this comes out again in “He Is The Kind”, where he is the kind of man that ‘discards teabags on the draining board, / despite my navigations to the compost bin’. In “In A Relationship (Pending)” the opening poem’s theme of exploration of the self as an estate agent’s guide is repeated/reprised.

However, towards the back end of the collection, we see things moving towards a happier ending (for now?). In “Fatter”, echoing “Thinner” from earlier, we see the poet declaring she has returned to her ‘fighting weight’ and after this man admits he preferred her ‘heroin chic of when we first met’ we see Edwards realising this is over…

The collection ends with of the ‘tranquilizing voice’ of “The Addiction Counsellor”. I was a little confused as to the proprietary nature of the relationship. While she edges ‘closer than fiduciary allows’, ‘He holds my hipbones / lightly as he passes me in the doorway.’

Perhaps it’s transference that causes this excitement, someone being kind is misinterpreted as being something else after the excuses for men that came before. However, it’s telling that it’s Edwards’ daughter that forms the voice of reason at the end. ‘She rightly reprimands / me for wolfing butterflies again.’ That note of caution is a wise one.

Estate agents are experts at shifting your perspective when they want to sell a house, taking photos at odd angles to make a house appear bigger, often somehow shifting a postcode to appear in a more desirable area or making a feature of the bus route that runs outside the house (Near to public transport…). I don’t know how good Rhian Edwards is as an estate agent, but she’s certainly learnt the tricks of shifting perspectives and making us look again at places and events we may have overlooked. I hope it’s not another eight years before we see a new collection.

Mat Riches