Poetry review – A COMMONPLACE: Stuart Henson reviews an intriguingly different mix of collection & anthology by Jonathan Davidson

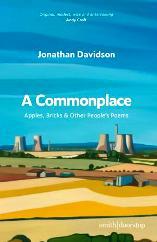

A Commonplace

Jonathan Davidson

Smith Doorstop, 2020

ISBN 978-1-912196-33-3

106pp £9.95

A Commonplace

Jonathan Davidson

Smith Doorstop, 2020

ISBN 978-1-912196-33-3

106pp £9.95

What do you get if you cross an anthology with a poetry reading? Something, I’d say, like Jonathan Davidson’s A Commonplace. It’s such a simple idea you’re left wondering why it hasn’t been done before. The logic works like this: people want to know a bit about where a poem has come from, the nitty-gritty of incident that led to its composition. And poems by different authors often resonate one with the other—in a kind of call and response. Put that together and you get an entertaining mix of anecdote, discovery and material for discussion.

Davidson wants to tell us about poems he likes, and poems he’s written. Sometimes indeed poems he’s written about poems he likes. So the individual pieces are interspersed with a director’s commentary, anticipating what’s coming up and reflecting on what’s gone before. Often the commentary is supplemented by ‘footnotes’ which are usually amusing asides—the sort of remarks you might throw away at a reading. (If you happen to have read my review of Davidson’s critical book On Poetry, you’ll know I have reservations about the footnoting. Now and then it gets a bit intense—like being in lockdown with half the cast of The News Quiz.) As an added bonus we also get a grid-referenced gazetteer and a bibliography at the end. For further research.

The book’s subtitle, Apples, Bricks & Other People’s Poems, gives you a fair idea of what you’re going to get, beginning with Richie McCaffery’s ‘Brick’ and a neat gloss on how a poem might ‘say one thing and mean another’. I should declare an interest here. Living as I do on the site of a Victorian brickworks, I’m keen that the oft-overlooked brick should get its moment in the sun. I’m partial to the odd sharp poem about an apple too. Davidson’s own brick poems veer towards the socio-political. The longest, ‘Utopia’, begins with something of a rant:

It’s an old brick in an old wall along the Old

Main Line Canal a kilometre west of here and I

Take a photo of it, and post the photo, and tweet

The photo and say something suitably ironic

About bricks and walls. I might as well have thrown

Myself in, there and then, because I had betrayed

My people with cheap words and fancy language

And knowing looks and an educated tongue: like:

What I don’t know about life isn’t worth knowing;

Like: I know so much about what we want and what

They wanted; like: I’ve done so much to get it.

Like fuck I have. And now they talk like the Right

Have won and that’s not a fucking problem. It is

A fucking problem. This brick stuck in this wall

With its arse showing the clay-cast word Utopia

Is the fucking problem. And you lot reading this

Are the fucking problem.

Now whilst this should go down well at the Lamb & Flag Open Mic, I’m not quite clear why we, the readers, are a problem. Unless it’s that anyone doing anything so bourgeois as reading a poetry book is by default a candidate for re-education. Frustratingly, the commentary doesn’t elucidate. Still, it would break the ice alright—and get a ‘conversation’ going.

The poem goes on directly to explain that

The leaves are turning

Early this year and we failed to pick all of the

Beautiful blackberries because we were watching

A long-form drama about some world that doesn’t

Exist but would be fun if it did.

Not just reading but watching too much opium-of-the-masses tele! What Comrade Davidson wants is a radical re-appraisal of that word Utopia. It should mean a place without homelessness and food-poverty and fuel-poverty—where everyone gets a sweet dark taste ‘Of the blackberries you pick even when the dusk / Is nearly upon you, and you are tired and alone’. I move…

The same spirit prompts another wish-poem, this time in response to Mick North’s fine polemic ‘Land’ which ends with the imperative ‘Do not let the wicked inherit the earth.’ Davidson has been riled by the ostentation of some of the houses he passes on his cycling excursions. Flash wealth is sickening: most of us can agree on that. And at the end the speaker offers the gated householders an opportunity for self-examination and restitution:

But, in time, the owners of these

period properties will be required

to declare themselves, and not

by swinging from a fresh gallows

at a crossroads on the border

of two rural counties,

but by coming with full hands and laying

at the feet of the people all

the wealth they are not due.

Ah! When the revolution comes! Though I fear they may have to be dragged kicking and screaming. As a fully paid-up member of the Brickworkers’ Collective, I’m sympathetic, but I have to say I prefer his two other brick poems. ‘Brick Life’ begins like one of those old-school homework assignments: imagine you’re a brick and tell the story of what’s happened in your life. The first six couplets recount the production process with a brick-lover’s relish:

Cut from the clay of the big pit, blade-bitten,

thumped and smacked, stacked up, left for dead

...

A master-class in alliteration, assonance and onomatopoeia. And after the firing the bricks

… wake in a kind of Hades, our hearts hard,

hollow seeming, and we hold our brittle breath.

If I were a teacher I’d have to give this one 10/10—for its sheer imaginative bravura and accomplishment. Interestingly, too, the poem develops a nice ambiguity as it works to its close.

We make the world, we do what we’re told,

go where they place us, in whatever bond,

and build the walls, hold the earth at bay,

culvert the rivers, shoulder the high roads,

tell ourselves we are happy, shout hurrah,

try to move but can’t; try to think, can’t.

Beyond the enjoyment, the intellectual amusement, of the brick-speak, that last line becomes just a little uncomfortable. The bricks are willing, worthy enough, and the process they’ve been through is terrifying, coercive. But now they are trapped, physically and psychologically. The repetition and the punctuation choke you at the end. At one level this could be the fate of the workers, exploited by their all-powerful ‘betters’. They have each become, partly through their own volition, just another brick in the societal wall. Yet at the same time, the Stakhanovite efforts of the bricks with their song ‘build we, build we, build we now the new’, their dutiful shouldering of the infrastructure, must surely remind us of the human cost of the Five Year Plans of a Stalinist dictatorship. I feel a bit of dialectic coming on.

The final brick poem ‘Brickwork’ celebrates the makers, the builders, in a more direct way, using the language of the trades to praise those who are now ‘dumb or gone away or dead’, playing gently on the connotations of ‘vernacular’ in reference to both language and architecture. These are the truly unacknowledged legislators, whose narratives can be read in the lines of the bricks they laid.

And so to the apples. What of them? ‘Apple Picking’ has a hint of Frost in its early lines: ‘They glitter / in the slight breeze. It takes a young man // and a tapered ladder and some nerve / to reach them’, but it goes its own way, recounting a tale of young love with a perfectly-judged resolution, which I won’t spoil here. ‘Miss Balcombe’s Orchard’ is darker but draws on the same period of the poet’s life, when, as he explains in the commentary, he was in his late teens and working for the eponymous owner. A death occurs, and as in Frost’s ‘Out, Out-’ the living are powerless to do much more than continue with their tasks. The poem’s effectiveness lies in the authenticity of detail. A line like ‘A vapour of petrol settled on the morning’ can tell so much.

The selection of work by ‘Other People’ is, as you would expect, consistently worthwhile. There are outstanding poems from Helen Dunmore, Pauline Stainer, Maura Dooley and Ann Atkinson among them—and almost certainly something that will be new to one or other of us. Davidson’s comments are mostly straightforward explanations of when or how he encountered the poems and the poets. We learn, for instance, that his first experiences of Paul Muldoon were at a ‘dull’ reading in Oxford when he was nineteen. He offers his own response ‘On, Why Brownlee Left’ which ploughs a similar furrow. The Muldoon poem is not, as it happens, included, which is a pity. Maybe Faber’s fee was too much. The same is true for ‘Live Broadcast’ though most readers will have already marked that down as a Larkin knock-off before he fesses up to it in the commentary a couple of pages on.

Of course, there’s more to this hundred page collection than apples, bricks and smart one-liners. There’s a nice example of ‘the ubiquitous poem about quadratic equations that troubles every slim volume of contemporary poetry’, for instance, and a metaphysical examination of the lustful nature of the printed word—or rather the inky nature of lust. The author’s parents feature in several poems. My favourite is ‘A Breakfast’ in which the son is enjoying his un-hurried breakfast alone:

And then you are there,

with a small pan of porridge,

taking your packed lunch from the fridge,

listening to the quiet radio,

reading a library book …

A memory-ghost, I think, but one that reminds me of the wonderful description of Paul Morel’s father in Sons and Lovers, sitting alone by the kitchen range making up his fuses before the day’s work. There are three short poems about the Civil War, and a number of travel observations that take us from Didcot and Llangollen to Kyiv and Venice…

In his concluding commentary, Davidson explains that he wants poems to read him. ‘And I want these poems to read you, to say what you might have said or thought.’ Leaving aside the rather modish idea of the poems doing the reading—is it simply that he wishes the poems to express his convictions and the thoughts we might have expressed had we but the words?—you can see where he’s coming from. ‘And while I’m at it, I ask you to take these poems and use them. By which I mean, share them in private correspondence, speak them in your own accent, compose your own – better – versions of them’ … ‘The sharing’s the thing.’

Well, what’s stopping you? Get involved!

Stuart Henson

Oct 20 2020

A Commonplace

Poetry review – A COMMONPLACE: Stuart Henson reviews an intriguingly different mix of collection & anthology by Jonathan Davidson

What do you get if you cross an anthology with a poetry reading? Something, I’d say, like Jonathan Davidson’s A Commonplace. It’s such a simple idea you’re left wondering why it hasn’t been done before. The logic works like this: people want to know a bit about where a poem has come from, the nitty-gritty of incident that led to its composition. And poems by different authors often resonate one with the other—in a kind of call and response. Put that together and you get an entertaining mix of anecdote, discovery and material for discussion.

Davidson wants to tell us about poems he likes, and poems he’s written. Sometimes indeed poems he’s written about poems he likes. So the individual pieces are interspersed with a director’s commentary, anticipating what’s coming up and reflecting on what’s gone before. Often the commentary is supplemented by ‘footnotes’ which are usually amusing asides—the sort of remarks you might throw away at a reading. (If you happen to have read my review of Davidson’s critical book On Poetry, you’ll know I have reservations about the footnoting. Now and then it gets a bit intense—like being in lockdown with half the cast of The News Quiz.) As an added bonus we also get a grid-referenced gazetteer and a bibliography at the end. For further research.

The book’s subtitle, Apples, Bricks & Other People’s Poems, gives you a fair idea of what you’re going to get, beginning with Richie McCaffery’s ‘Brick’ and a neat gloss on how a poem might ‘say one thing and mean another’. I should declare an interest here. Living as I do on the site of a Victorian brickworks, I’m keen that the oft-overlooked brick should get its moment in the sun. I’m partial to the odd sharp poem about an apple too. Davidson’s own brick poems veer towards the socio-political. The longest, ‘Utopia’, begins with something of a rant:

Now whilst this should go down well at the Lamb & Flag Open Mic, I’m not quite clear why we, the readers, are a problem. Unless it’s that anyone doing anything so bourgeois as reading a poetry book is by default a candidate for re-education. Frustratingly, the commentary doesn’t elucidate. Still, it would break the ice alright—and get a ‘conversation’ going.

The poem goes on directly to explain that

Not just reading but watching too much opium-of-the-masses tele! What Comrade Davidson wants is a radical re-appraisal of that word Utopia. It should mean a place without homelessness and food-poverty and fuel-poverty—where everyone gets a sweet dark taste ‘Of the blackberries you pick even when the dusk / Is nearly upon you, and you are tired and alone’. I move…

The same spirit prompts another wish-poem, this time in response to Mick North’s fine polemic ‘Land’ which ends with the imperative ‘Do not let the wicked inherit the earth.’ Davidson has been riled by the ostentation of some of the houses he passes on his cycling excursions. Flash wealth is sickening: most of us can agree on that. And at the end the speaker offers the gated householders an opportunity for self-examination and restitution:

Ah! When the revolution comes! Though I fear they may have to be dragged kicking and screaming. As a fully paid-up member of the Brickworkers’ Collective, I’m sympathetic, but I have to say I prefer his two other brick poems. ‘Brick Life’ begins like one of those old-school homework assignments: imagine you’re a brick and tell the story of what’s happened in your life. The first six couplets recount the production process with a brick-lover’s relish:

A master-class in alliteration, assonance and onomatopoeia. And after the firing the bricks

… wake in a kind of Hades, our hearts hard,

hollow seeming, and we hold our brittle breath.

If I were a teacher I’d have to give this one 10/10—for its sheer imaginative bravura and accomplishment. Interestingly, too, the poem develops a nice ambiguity as it works to its close.

Beyond the enjoyment, the intellectual amusement, of the brick-speak, that last line becomes just a little uncomfortable. The bricks are willing, worthy enough, and the process they’ve been through is terrifying, coercive. But now they are trapped, physically and psychologically. The repetition and the punctuation choke you at the end. At one level this could be the fate of the workers, exploited by their all-powerful ‘betters’. They have each become, partly through their own volition, just another brick in the societal wall. Yet at the same time, the Stakhanovite efforts of the bricks with their song ‘build we, build we, build we now the new’, their dutiful shouldering of the infrastructure, must surely remind us of the human cost of the Five Year Plans of a Stalinist dictatorship. I feel a bit of dialectic coming on.

The final brick poem ‘Brickwork’ celebrates the makers, the builders, in a more direct way, using the language of the trades to praise those who are now ‘dumb or gone away or dead’, playing gently on the connotations of ‘vernacular’ in reference to both language and architecture. These are the truly unacknowledged legislators, whose narratives can be read in the lines of the bricks they laid.

And so to the apples. What of them? ‘Apple Picking’ has a hint of Frost in its early lines: ‘They glitter / in the slight breeze. It takes a young man // and a tapered ladder and some nerve / to reach them’, but it goes its own way, recounting a tale of young love with a perfectly-judged resolution, which I won’t spoil here. ‘Miss Balcombe’s Orchard’ is darker but draws on the same period of the poet’s life, when, as he explains in the commentary, he was in his late teens and working for the eponymous owner. A death occurs, and as in Frost’s ‘Out, Out-’ the living are powerless to do much more than continue with their tasks. The poem’s effectiveness lies in the authenticity of detail. A line like ‘A vapour of petrol settled on the morning’ can tell so much.

The selection of work by ‘Other People’ is, as you would expect, consistently worthwhile. There are outstanding poems from Helen Dunmore, Pauline Stainer, Maura Dooley and Ann Atkinson among them—and almost certainly something that will be new to one or other of us. Davidson’s comments are mostly straightforward explanations of when or how he encountered the poems and the poets. We learn, for instance, that his first experiences of Paul Muldoon were at a ‘dull’ reading in Oxford when he was nineteen. He offers his own response ‘On, Why Brownlee Left’ which ploughs a similar furrow. The Muldoon poem is not, as it happens, included, which is a pity. Maybe Faber’s fee was too much. The same is true for ‘Live Broadcast’ though most readers will have already marked that down as a Larkin knock-off before he fesses up to it in the commentary a couple of pages on.

Of course, there’s more to this hundred page collection than apples, bricks and smart one-liners. There’s a nice example of ‘the ubiquitous poem about quadratic equations that troubles every slim volume of contemporary poetry’, for instance, and a metaphysical examination of the lustful nature of the printed word—or rather the inky nature of lust. The author’s parents feature in several poems. My favourite is ‘A Breakfast’ in which the son is enjoying his un-hurried breakfast alone:

A memory-ghost, I think, but one that reminds me of the wonderful description of Paul Morel’s father in Sons and Lovers, sitting alone by the kitchen range making up his fuses before the day’s work. There are three short poems about the Civil War, and a number of travel observations that take us from Didcot and Llangollen to Kyiv and Venice…

In his concluding commentary, Davidson explains that he wants poems to read him. ‘And I want these poems to read you, to say what you might have said or thought.’ Leaving aside the rather modish idea of the poems doing the reading—is it simply that he wishes the poems to express his convictions and the thoughts we might have expressed had we but the words?—you can see where he’s coming from. ‘And while I’m at it, I ask you to take these poems and use them. By which I mean, share them in private correspondence, speak them in your own accent, compose your own – better – versions of them’ … ‘The sharing’s the thing.’

Well, what’s stopping you? Get involved!

Stuart Henson