Poetry review – VERITAS: Alwyn Marriage is impressed by Jacqueline Saphra’s skilfully crafted poetic responses to the paintings of Artemisia Gentileschi

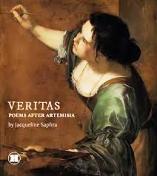

Veritas, Poems after Artemisia,

Jacqueline Saphra

Hercules Editions, 2020

ISBN 978-1-916971-1-4

48 pages £10.

Veritas, Poems after Artemisia,

Jacqueline Saphra

Hercules Editions, 2020

ISBN 978-1-916971-1-4

48 pages £10.

Relatively few poets are up to the challenge of perfecting even a simple sonnet corona, or crown of sonnets, in which the last line of each sonnet becomes the first line of the next. However, Saphra, who is admittedly no stranger to the sonnet form has, in Veritas, gone further, producing an impressive sonnet redoublé or heroic crown. This more sophisticated version of the form comprises fifteen sonnets, in each of which the first line is a repeat of the last line of the previous sonnet, as in a normal sonnet corona, but which then concludes with a fifteenth sonnet, formed of all the preceding first lines in the correct order.

Such a controlled form could so easily result in artificial diction, but these poems in Veritas flow seamlessly and so naturally that it is almost as though the poet is talking to us through the paintings she is celebrating. The sonnet form Saphra employs is the English, or Shakespearean sonnet, that works so well in our language and has been used by poets as different as Wyatt, George Herbert and Wilfred Owen.

It is, perhaps, ironic that this beautiful sonnet corona should have emerged into the light of day during the ‘corona’ pandemic; but that is, of course, no more than an unfortunate coincidence of language. The wretched virus may look a little like a crown when under a microscope, but after these last few months I should think we would all agree that there is nothing to celebrate in it.

Celebration, however, is the nature of Saphra’s poems about the paintings of the great Italian Renaissance artist, Artemisia Gentileschi. If it had not been for C19, the National Gallery would have been mounting an exhibition of Gentileschi’s work this spring. We do not yet know when we will be able to see the postponed exhibition, but in the meantime we can learn a great deal about her work from this book.

We are privileged indeed that this small but exquisite book, published by Hercules Editions, contains not just Saphra’s reactions in poetry to the works of art, but fine full-colour reproductions of the paintings about which she has chosen to write. All of the works focus on women, from classical figures to biblical characters, plus a few self-portraits in which Artemisia appears as, for instance, St Catherine, as a lute-player and as an allegory of Painting.

Saphra also enters fully into the blood and gore of some of the Old Testament stories that Gentileschi has portrayed so graphically in her art, a couple of which, of course, include the gory representation of decapitation (“Judith and her Maidservant”, “Judith and Holofernes”). Somewhat surprisingly, Saphra does not include a poem on the subject of the Jael and Sisera painting that she tells us, in her essay at the end of the book, was the Gentileschi work that first caught her attention, when she was researching her own middle name.

However, there is beauty and delicacy as well as the drama of the more bloodthirsty paintings.

On hearing the decree, Mary's hand

drifts to her heart as she waves the other:

does she mean to push away or bless

the messenger?

("The Annunciation, 1630")

I particularly enjoyed this fine Annunciation poem, which offers a slant on the New Testament event that is rather different from many other well-known representations, and includes the deliciously humorous concept of Gabriel as ‘well-overdressed’.

As one would expect, and hope, this collection by Saphra is unashamedly feminist. Some of the poems raise important feminist questions, such as in the sonnet “Lucretia”, which brings out the intense personal feelings of the artist who knew only too well what it was to have been raped, and who had to fight prejudice and injustice in order to establish herself as an independent artist. Saphra successfully brings out this particular gutsy quality in Gentileschi’s work.

I won't be plundered, fooled or colonised

("Susannah ad the Elders, 1610")

I take my chances, make a better life,

part of a sisterhood of ruined women

("Lucretia, 1620-21")

It is true that some of the women represented are ‘ruined’, but none are weak or subservient. I was sorry that Mary Magdalene, the close friend of Jesus and first apostle, should once more be portrayed as a penitent whore; but the fault lies in historical misrepresentations of Mary’s role, rather than in Gentileschi or in Saphra, both of whom were simply responding to the story as they received and saw it.

It is appropriate that the concluding poem, “Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura)” should celebrate art itself rather than a particular historical figure; and this final gem of the corona is impressive in the way that, made up of the foregoing first lines as it is, it flows so gracefully that one is not aware of the device being used.

The book begins with an introduction on “Artemisia: Life and Reputation” by the art historian Dr Jordana Pomeroy, director of the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum in Miami, Florida; and it concludes with an enlightening personal afterword by the author. It is an attractive small book, lovely to hold and a joy to read. I sincerely hope that the small size of the book, which is one of its many attractions, doesn’t suggest to anyone that the book is in any way insubstantial. It most certainly is not.

.

Alwyn Marriage

Jul 2 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Jacqueline Saphra

Poetry review – VERITAS: Alwyn Marriage is impressed by Jacqueline Saphra’s skilfully crafted poetic responses to the paintings of Artemisia Gentileschi

Relatively few poets are up to the challenge of perfecting even a simple sonnet corona, or crown of sonnets, in which the last line of each sonnet becomes the first line of the next. However, Saphra, who is admittedly no stranger to the sonnet form has, in Veritas, gone further, producing an impressive sonnet redoublé or heroic crown. This more sophisticated version of the form comprises fifteen sonnets, in each of which the first line is a repeat of the last line of the previous sonnet, as in a normal sonnet corona, but which then concludes with a fifteenth sonnet, formed of all the preceding first lines in the correct order.

Such a controlled form could so easily result in artificial diction, but these poems in Veritas flow seamlessly and so naturally that it is almost as though the poet is talking to us through the paintings she is celebrating. The sonnet form Saphra employs is the English, or Shakespearean sonnet, that works so well in our language and has been used by poets as different as Wyatt, George Herbert and Wilfred Owen.

It is, perhaps, ironic that this beautiful sonnet corona should have emerged into the light of day during the ‘corona’ pandemic; but that is, of course, no more than an unfortunate coincidence of language. The wretched virus may look a little like a crown when under a microscope, but after these last few months I should think we would all agree that there is nothing to celebrate in it.

Celebration, however, is the nature of Saphra’s poems about the paintings of the great Italian Renaissance artist, Artemisia Gentileschi. If it had not been for C19, the National Gallery would have been mounting an exhibition of Gentileschi’s work this spring. We do not yet know when we will be able to see the postponed exhibition, but in the meantime we can learn a great deal about her work from this book.

We are privileged indeed that this small but exquisite book, published by Hercules Editions, contains not just Saphra’s reactions in poetry to the works of art, but fine full-colour reproductions of the paintings about which she has chosen to write. All of the works focus on women, from classical figures to biblical characters, plus a few self-portraits in which Artemisia appears as, for instance, St Catherine, as a lute-player and as an allegory of Painting.

Saphra also enters fully into the blood and gore of some of the Old Testament stories that Gentileschi has portrayed so graphically in her art, a couple of which, of course, include the gory representation of decapitation (“Judith and her Maidservant”, “Judith and Holofernes”). Somewhat surprisingly, Saphra does not include a poem on the subject of the Jael and Sisera painting that she tells us, in her essay at the end of the book, was the Gentileschi work that first caught her attention, when she was researching her own middle name.

However, there is beauty and delicacy as well as the drama of the more bloodthirsty paintings.

On hearing the decree, Mary's hand drifts to her heart as she waves the other: does she mean to push away or bless the messenger? ("The Annunciation, 1630")I particularly enjoyed this fine Annunciation poem, which offers a slant on the New Testament event that is rather different from many other well-known representations, and includes the deliciously humorous concept of Gabriel as ‘well-overdressed’.

As one would expect, and hope, this collection by Saphra is unashamedly feminist. Some of the poems raise important feminist questions, such as in the sonnet “Lucretia”, which brings out the intense personal feelings of the artist who knew only too well what it was to have been raped, and who had to fight prejudice and injustice in order to establish herself as an independent artist. Saphra successfully brings out this particular gutsy quality in Gentileschi’s work.

I won't be plundered, fooled or colonised ("Susannah ad the Elders, 1610") I take my chances, make a better life, part of a sisterhood of ruined women ("Lucretia, 1620-21")It is true that some of the women represented are ‘ruined’, but none are weak or subservient. I was sorry that Mary Magdalene, the close friend of Jesus and first apostle, should once more be portrayed as a penitent whore; but the fault lies in historical misrepresentations of Mary’s role, rather than in Gentileschi or in Saphra, both of whom were simply responding to the story as they received and saw it.

It is appropriate that the concluding poem, “Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura)” should celebrate art itself rather than a particular historical figure; and this final gem of the corona is impressive in the way that, made up of the foregoing first lines as it is, it flows so gracefully that one is not aware of the device being used.

The book begins with an introduction on “Artemisia: Life and Reputation” by the art historian Dr Jordana Pomeroy, director of the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum in Miami, Florida; and it concludes with an enlightening personal afterword by the author. It is an attractive small book, lovely to hold and a joy to read. I sincerely hope that the small size of the book, which is one of its many attractions, doesn’t suggest to anyone that the book is in any way insubstantial. It most certainly is not.

.

Alwyn Marriage