Poetry review – The Sailors of Ulm: Neil Fulwood marvels that the bizarre workings of Andy Croft’s imagination can be contained within such well-crafted formalism

The Sailors of Ulm

Andy Croft

Shoestring Press

ISBN 978-1-912524-48-8

£10.00

The Sailors of Ulm

Andy Croft

Shoestring Press

ISBN 978-1-912524-48-8

£10.00

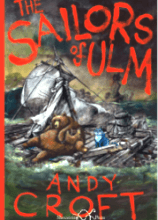

It’s an old adage that one should not judge a book by its cover, but with The Sailors of Ulm it seems apposite to at least appreciate the cover. By Martin Rowson, it parodies Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa to splendid effect, setting the tone for much of the scalpel-sharp satire that graces the pages within.

The back cover deserves a glance, too. Like many books, the blurb includes some quotes pertinent to Croft’s previous publications. There are six short epithets on the back cover of The Sailors of Ulm, including such luminaries as Merryn Williams, who praises Croft’s “wit, passion and verbal dexterity”, and John Hartley Williams, who considers him “the Alexander Pope of the North”. And then there are these two, quoted here in full: “dreadfully old fashioned” (Tribune) and “puerile” (TLS). This tells us two things: (1) Andy Croft is a committed and unapologetic formalist; (2) Andy Croft doesn’t give a flying one about trends, acceptance or the poetry establishment in general.

But this is hardly news: Croft has for years now been ploughing his own furrow, swatting away brickbats and disapprobation as if they were merely flies at a summer picnic. Old school leftist, taker-on of social and political hypocrisy, and no stranger to controversy in much the same way that Oliver Reed was no stranger to the odd pint or two, it’s safe to say that Croft is a unique talent in contemporary British poetry, and his particular brand of (to use an inelegant euphemism) piss and vinegar often provides the shake-up that the poetry scene needs.

Croft and Shoestring are a good fit. Shoestring owner/editor John Lucas has similarly spent decades ploughing his own furrow, taking a chance on poets the mainstream would edge away from, and building up an astounding roster of beautifully produced publications. Shoestring previously published Croft’s Letters to Randall Swingler (2017), a sequence of four extended verse-letters to the criminally underappreciated poet and activist in which Croft explores and critiques the state of the nation. The last of these coincided with the EU referendum; things, as the poems in The Sailors of Ulm attest, haven’t got much better since then.

Which isn’t to say that the collection comprises gripe after grumble after disaffection or that it’s nothing but, as my grandfather would have put it, pit ’n’ bloody politics. Croft has always thrown the net of his inspiration wide, and his rigorous if unsubtle wit ensures that things never fully veer into cant or rhetoric.

The subject matter and geographical range of The Sailors of Ulm is fascinating: from Victor Pasmore’s brutalist Apollo Pavilion in Peterlee to Willimantic in Connecticut, scene of a battle between townsfolk and, uh, frogs; from Prior Park in Combe Down to Tomskaya Pisanitsa Park in Kemerovo; from Russian cosmonauts to a surprise appearance from Don Marquis’s typewriter-tapping cockroach Archy, Croft seizes on place, character and incident with glee, smelting it into an aesthetic that is entirely his own.

His facility with set forms is just as impressive, particularly in regard to ottava rima. Having already distinguished himself with the form in Letters to Randall Swingler, Croft delivers a tour de force in ‘Don and Donna’, which originally appeared in the Five Leaves anthology A Modern Don Juan (edited by Croft and N.S. Thompson). It’s the perfect centrepiece for The Sailors of Ulm, aiming its barbs at a range of targets from the prison system to the poetry establishment, specifically the kind of profile-showing “poet – Spoken Word Performer, please!” whose “Glasto set last year was download gold”.

What really marks out the collection, though, is the parade of historical figures who march through its pages – sporting heroes, musicians, activists and literary giants rub shoulders. By way of example, here’s the sonnet ‘Paul Robeson Sings in Mudfog Town Hall’, quoted in full (Croft isn’t always succinct and quite a few of the poems herein unspool over multiple pages, almost defying the reviewer to snip out a handy little quote):

And when at last they gave his passport back

He made a tour of Northern small town halls,

Still handsome, clever, radical and black,

His voice still strong enough to shake the walls.

But though the place was packed, the three front-rows

(Reserved for all the local great and good)

Were pointedly unoccupied by those

Apparently afraid of brotherhood.

Though no-one who was anyone was there,

The no-ones who are everybody came -

The nobodies who know that everywhere

There’s somebody who thinks they’re not the same,

As if there’s anybody could delay

The walls of privilege tumbling down one day.

The man, his presence, his talent, his politics; the turn exactly where it should be in a sonnet, then Croft pulls in the town hall’s entire audience and all their comrades and forebears and everyone who dreams of a better, fairer world.

Elsewhere, ‘The Last Act of Harry Patch’ is a downbeat cogitation on a similar theme, the poem weighing up of the centenarian activist’s wartime experience and subsequent espousal of pacifism against the venal hypocrisy of our contemporary politicians, those purveyors of nationalistic and pro-militarist rhetoric, who

Come crawling out from Number 10

To bury him with loud laudation

And hymns to reconciliation –

The poisonous forked-tongue response

Of those who tried to kill him once,

Who justify each round of killing

From Langemarck to Afghanistan,

Then shed a tear for one old man.

Croft’s fury is justified: Patch had no time for the very politicians who sought to parlay approval points currency by eulogising him after his death. “War is organised murder and nothing else,” Patch famously declared, a quote that precedes the poem.

John Berger, Alexei Leonov, Martin Espada and many others put in appearances, and to discuss them all would push this review toward an untenable length. I’ll leave you to consider what is perhaps Croft’s most surreal offering, ‘Booked’. The opening stanza oozes atmosphere, as if a Val Newton RKO horror had been adapted from a rhyming screenplay:

His hair is grey, though not with years,

His limbs are bowed, though not with toil,

His eyes are red, though not with tears,

His chamber lit by midnight oil,

A shadow of his former self -

A writer left upon the shelf.

Since books are written now by readers

Who may discover in the text

What those of us who write the bleeders

Do not intend, what follows next

Is that unless a book is read

It is (like modern authors) dead ...

Written for Nottingham City of Literature’s Dawn of the Unread anthology, edited by James Walker, ‘Booked’ quite literally combines two of that city’s most swaggering heroes: Lord Byron and Brian Clough. The poem is both a rallying cry for adult literacy and a zombie story, though not one that fans of The Walking Dead would necessarily recognise! I’ll say no more and let you discover the bizarre workings of Croft’s imagination for yourselves.

Jun 2 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Andy Croft

Poetry review – The Sailors of Ulm: Neil Fulwood marvels that the bizarre workings of Andy Croft’s imagination can be contained within such well-crafted formalism

It’s an old adage that one should not judge a book by its cover, but with The Sailors of Ulm it seems apposite to at least appreciate the cover. By Martin Rowson, it parodies Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa to splendid effect, setting the tone for much of the scalpel-sharp satire that graces the pages within.

The back cover deserves a glance, too. Like many books, the blurb includes some quotes pertinent to Croft’s previous publications. There are six short epithets on the back cover of The Sailors of Ulm, including such luminaries as Merryn Williams, who praises Croft’s “wit, passion and verbal dexterity”, and John Hartley Williams, who considers him “the Alexander Pope of the North”. And then there are these two, quoted here in full: “dreadfully old fashioned” (Tribune) and “puerile” (TLS). This tells us two things: (1) Andy Croft is a committed and unapologetic formalist; (2) Andy Croft doesn’t give a flying one about trends, acceptance or the poetry establishment in general.

But this is hardly news: Croft has for years now been ploughing his own furrow, swatting away brickbats and disapprobation as if they were merely flies at a summer picnic. Old school leftist, taker-on of social and political hypocrisy, and no stranger to controversy in much the same way that Oliver Reed was no stranger to the odd pint or two, it’s safe to say that Croft is a unique talent in contemporary British poetry, and his particular brand of (to use an inelegant euphemism) piss and vinegar often provides the shake-up that the poetry scene needs.

Croft and Shoestring are a good fit. Shoestring owner/editor John Lucas has similarly spent decades ploughing his own furrow, taking a chance on poets the mainstream would edge away from, and building up an astounding roster of beautifully produced publications. Shoestring previously published Croft’s Letters to Randall Swingler (2017), a sequence of four extended verse-letters to the criminally underappreciated poet and activist in which Croft explores and critiques the state of the nation. The last of these coincided with the EU referendum; things, as the poems in The Sailors of Ulm attest, haven’t got much better since then.

Which isn’t to say that the collection comprises gripe after grumble after disaffection or that it’s nothing but, as my grandfather would have put it, pit ’n’ bloody politics. Croft has always thrown the net of his inspiration wide, and his rigorous if unsubtle wit ensures that things never fully veer into cant or rhetoric.

The subject matter and geographical range of The Sailors of Ulm is fascinating: from Victor Pasmore’s brutalist Apollo Pavilion in Peterlee to Willimantic in Connecticut, scene of a battle between townsfolk and, uh, frogs; from Prior Park in Combe Down to Tomskaya Pisanitsa Park in Kemerovo; from Russian cosmonauts to a surprise appearance from Don Marquis’s typewriter-tapping cockroach Archy, Croft seizes on place, character and incident with glee, smelting it into an aesthetic that is entirely his own.

His facility with set forms is just as impressive, particularly in regard to ottava rima. Having already distinguished himself with the form in Letters to Randall Swingler, Croft delivers a tour de force in ‘Don and Donna’, which originally appeared in the Five Leaves anthology A Modern Don Juan (edited by Croft and N.S. Thompson). It’s the perfect centrepiece for The Sailors of Ulm, aiming its barbs at a range of targets from the prison system to the poetry establishment, specifically the kind of profile-showing “poet – Spoken Word Performer, please!” whose “Glasto set last year was download gold”.

What really marks out the collection, though, is the parade of historical figures who march through its pages – sporting heroes, musicians, activists and literary giants rub shoulders. By way of example, here’s the sonnet ‘Paul Robeson Sings in Mudfog Town Hall’, quoted in full (Croft isn’t always succinct and quite a few of the poems herein unspool over multiple pages, almost defying the reviewer to snip out a handy little quote):

The man, his presence, his talent, his politics; the turn exactly where it should be in a sonnet, then Croft pulls in the town hall’s entire audience and all their comrades and forebears and everyone who dreams of a better, fairer world.

Elsewhere, ‘The Last Act of Harry Patch’ is a downbeat cogitation on a similar theme, the poem weighing up of the centenarian activist’s wartime experience and subsequent espousal of pacifism against the venal hypocrisy of our contemporary politicians, those purveyors of nationalistic and pro-militarist rhetoric, who

Croft’s fury is justified: Patch had no time for the very politicians who sought to parlay approval points currency by eulogising him after his death. “War is organised murder and nothing else,” Patch famously declared, a quote that precedes the poem.

John Berger, Alexei Leonov, Martin Espada and many others put in appearances, and to discuss them all would push this review toward an untenable length. I’ll leave you to consider what is perhaps Croft’s most surreal offering, ‘Booked’. The opening stanza oozes atmosphere, as if a Val Newton RKO horror had been adapted from a rhyming screenplay:

Written for Nottingham City of Literature’s Dawn of the Unread anthology, edited by James Walker, ‘Booked’ quite literally combines two of that city’s most swaggering heroes: Lord Byron and Brian Clough. The poem is both a rallying cry for adult literacy and a zombie story, though not one that fans of The Walking Dead would necessarily recognise! I’ll say no more and let you discover the bizarre workings of Croft’s imagination for yourselves.