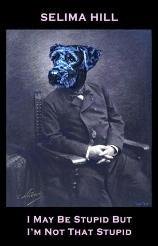

Poetry review – I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid: Charles Rammelkamp finds puzzles to enjoy in Selima Hill’s substantial collection

I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid

Selima Hill

Bloodaxe Books 2019

ISBN: 978-1780371917

152 pages $17.95 / £12

I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid

Selima Hill

Bloodaxe Books 2019

ISBN: 978-1780371917

152 pages $17.95 / £12

The six sequences that make up Selima Hill’s new collection are composed of poems that are like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle you must put together to see the full picture. This is nowhere more evident than in the final section, “Helpless with Laughter,” which is literally made up poems with titles of body parts! Like almost all the (300-plus) poems in this collection, the poems in this section are usually 4-line aphorisms, observations that are like haiku (or tanka) with attitude. The sixty-nine poems that make up this section are arranged alphabetically from “Ankles” to “Wristbone.” A little past the middle is this six-line poem called “Navel,” which includes an allusion to the poet’s mother, an important theme in the overall jigsaw that is I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid:

Thankful for small mercies as I am,

such as that I’m not afraid of wasps,

I’m thankful for the navel which a stranger

knotted for me late one autumn night

outside an upstairs room in which my mother

was praying I was just a bad dream.

Indeed, the poet’s relationship with her mother is complex. The second section, devoted to poems about her mother, “My Mother and Me on the Eve of the Chess Championships,” is one of the two longest in this collection, along with the first section, “Elective Mute,” whose poems focus on the poet herself.

The other three sections of the book are “Fishtank” which focuses on her brother; “Lambchop” which deals with a sort of creepy “elderly silver-haired gentleman” who may be her father; and “The Boxer Klitschko” which is about a favorite uncle and some indistinguishable aunts, as well as Hill’s own love of swimming. Together, all of these poems illuminate and explicate the puzzle that is the poet herself.

But it’s the mother who figures prominently throughout. Even the section spotlighting the uncle and aunts, an interlude by the sea where she tastes “freedom,” or something like it, concludes with a poem called “What My Mother Wanted”:

It felt so good to be so disobedient,

to take no notice of my frantic mother

who wanted me to give her what she wanted

but neither of us knew what that was;

it felt so sweet to be so uncontrollable

and not to know what happens to the wronged.

The poems in the first section, “Elective Mute,” portray the poet as a loner, an outsider, clearly on the autism spectrum, alienated from her family and everybody else (in one poem she muses that she gets along better with children but as a child got along better with adults). She hates being touched. She has trouble making conversation. She laughs inappropriately at the wrong times. The poem, “I’m Sorry But I Think I Might Be Real,” the sixth one in with another three hundred and twenty or so to go, seems to anticipate her mother’s wish that she’s just a bad dream.

While she does not get the love from her mother that we like to think children deserve – a “birthright,” indeed – the two of them are nevertheless entwined so closely it’s almost suffocating, disappointing though they are to one another. By contrast, “the elderly silver-haired gentleman” that we encounter in the “Lambchop” poems, whom we infer is her father, is distant, remote. She writes in “The Lamb”:

He thought I was his lamb and he could slaughter me

but he was wrong. He should have known. Alas,

I ran away; I ran like the wind;

I ran for fifty years without stopping.

In “The Bucket” we read, “He had no friends, he had outlived them all, / the funeral passes almost unnoticed,” and in the poem that follows, “I didn’t even go to the funeral. What’s the point?”

But her mother? “Every day she chirrups like a bird. / Every day I jingle like her chain.” (“My Mother Like a Bird”) “My mother disapproves of small children, / anyone who’s ill and lazy wives // but, most of all, she disapproves of me” (“My Mother and Small Children”). “I think my mother’s frightened of me sometimes: / I’m up all night; I’ve got no friends; I scowl.” (“My Mother’s Sponge”) The poem from the first section entitled simply, “My Mother” sums this all up succinctly:

Everyone is strange, but, alas,

my mother is the strangest of them all.

She seems to be so disappointed in me.

Also, it’s as if she’s afraid of me.

But none of these observations seems a cri de coeur or is in the least bit resentful. Hill simply puts the jigsaw pieces of her puzzling life together in her own droll fashion, the way things were, the way they are. And there is a lot of deadpan humor throughout these poems, evident in the very title of the book, albeit dark at times. The two-line poem, “PLEASE CARRY DOGS” reads:

When I see the sign I turn back

because I haven’t got a dog to carry.

The last poem in the Mother section is likewise an amusing, poker-faced conjecture entitled “My Mother in Heaven” (“if there is such a place”), which is the closest Hill comes to being elegiac. Other poems like “In Love with Roger Federer” are likewise clever but at the same time highlight her perceived shortcomings (“I know it isn’t clever to be clever…and not to be in love with Roger Federer….”).

The poet Fiona Sampson has called Selima Hill a “brilliant lyricist of human darkness.” So true! Read I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid and see why.

May 24 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Selima Hill

Poetry review – I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid: Charles Rammelkamp finds puzzles to enjoy in Selima Hill’s substantial collection

The six sequences that make up Selima Hill’s new collection are composed of poems that are like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle you must put together to see the full picture. This is nowhere more evident than in the final section, “Helpless with Laughter,” which is literally made up poems with titles of body parts! Like almost all the (300-plus) poems in this collection, the poems in this section are usually 4-line aphorisms, observations that are like haiku (or tanka) with attitude. The sixty-nine poems that make up this section are arranged alphabetically from “Ankles” to “Wristbone.” A little past the middle is this six-line poem called “Navel,” which includes an allusion to the poet’s mother, an important theme in the overall jigsaw that is I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid:

Indeed, the poet’s relationship with her mother is complex. The second section, devoted to poems about her mother, “My Mother and Me on the Eve of the Chess Championships,” is one of the two longest in this collection, along with the first section, “Elective Mute,” whose poems focus on the poet herself.

The other three sections of the book are “Fishtank” which focuses on her brother; “Lambchop” which deals with a sort of creepy “elderly silver-haired gentleman” who may be her father; and “The Boxer Klitschko” which is about a favorite uncle and some indistinguishable aunts, as well as Hill’s own love of swimming. Together, all of these poems illuminate and explicate the puzzle that is the poet herself.

But it’s the mother who figures prominently throughout. Even the section spotlighting the uncle and aunts, an interlude by the sea where she tastes “freedom,” or something like it, concludes with a poem called “What My Mother Wanted”:

The poems in the first section, “Elective Mute,” portray the poet as a loner, an outsider, clearly on the autism spectrum, alienated from her family and everybody else (in one poem she muses that she gets along better with children but as a child got along better with adults). She hates being touched. She has trouble making conversation. She laughs inappropriately at the wrong times. The poem, “I’m Sorry But I Think I Might Be Real,” the sixth one in with another three hundred and twenty or so to go, seems to anticipate her mother’s wish that she’s just a bad dream.

While she does not get the love from her mother that we like to think children deserve – a “birthright,” indeed – the two of them are nevertheless entwined so closely it’s almost suffocating, disappointing though they are to one another. By contrast, “the elderly silver-haired gentleman” that we encounter in the “Lambchop” poems, whom we infer is her father, is distant, remote. She writes in “The Lamb”:

In “The Bucket” we read, “He had no friends, he had outlived them all, / the funeral passes almost unnoticed,” and in the poem that follows, “I didn’t even go to the funeral. What’s the point?”

But her mother? “Every day she chirrups like a bird. / Every day I jingle like her chain.” (“My Mother Like a Bird”) “My mother disapproves of small children, / anyone who’s ill and lazy wives // but, most of all, she disapproves of me” (“My Mother and Small Children”). “I think my mother’s frightened of me sometimes: / I’m up all night; I’ve got no friends; I scowl.” (“My Mother’s Sponge”) The poem from the first section entitled simply, “My Mother” sums this all up succinctly:

But none of these observations seems a cri de coeur or is in the least bit resentful. Hill simply puts the jigsaw pieces of her puzzling life together in her own droll fashion, the way things were, the way they are. And there is a lot of deadpan humor throughout these poems, evident in the very title of the book, albeit dark at times. The two-line poem, “PLEASE CARRY DOGS” reads:

The last poem in the Mother section is likewise an amusing, poker-faced conjecture entitled “My Mother in Heaven” (“if there is such a place”), which is the closest Hill comes to being elegiac. Other poems like “In Love with Roger Federer” are likewise clever but at the same time highlight her perceived shortcomings (“I know it isn’t clever to be clever…and not to be in love with Roger Federer….”).

The poet Fiona Sampson has called Selima Hill a “brilliant lyricist of human darkness.” So true! Read I May Be Stupid But I’m Not That Stupid and see why.