Poetry Review – This Tilting Earth: Adele Ward reviews Jane Lovell’s new pamphlet which is full of concern for our planet

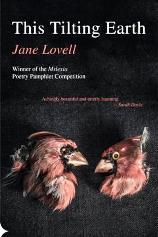

This Tilting Earth

Jane Lovell

Seren

ISBN 978-1-78172-525-2

32 pp £5.00

This Tilting Earth

Jane Lovell

Seren

ISBN 978-1-78172-525-2

32 pp £5.00

Jane Lovell’s latest pamphlet This Tilting Earth was the winner of the prestigious Mslexia Poetry Pamphlet Competition, which leads to publication by Seren. Although it’s a short collection, the poems open themselves up to much wider vistas – especially if read alongside methods for further research. My first reading, while travelling on the tube, depended solely on the poems, but reading them a second time at home, with the possibility of online searches, was a completely different experience. Some reviewers have said notes for the poems would have helped, but perhaps the point is to tempt readers to engage in research.

Some poems, such as ‘Limousin, Lascaux’, refer to relatively familiar subjects – in this case the cave paintings – although even in this instance I enjoyed finding images online. The poem adds to our view of the paintings with a sense of colour and movement, for example in the lines:

Of charcoal and cinnamon and ochre,

umber burnt and blown through bone or reed,

they balance on mist…

and the creatures are given momentum, creating a meeting of lives across the millennia, including ancient and modern human lives:

Twenty thousand years a secret,

they pause at the light, toss their blank faces,

eyes rolling to a thin discarded moon and back towards us

then lumber towards us, jostle to stare, poised

to bolt…

This poem stands out for me, as does the opening poem ‘Song of the Vogelherd Horse’, which required an image search online and worked best with a mental picture of the minimalist sculpture of a curved horse carved from a mammoth tusk. It starts ‘I am curved air/or water over stone’, a perfect combination of metaphors for the smoothness and rounded shape of this piece of ancient art. Our connection with our early ancestors is suggested in lines such as ‘Existing in two worlds/I find footholds in moments/cast off by ice’ and also ‘I was here before your god./Cherish my broken form.’

The theme of mammoths and human interaction with these extraordinary creatures continues into the next sequence, titled like the pamphlet ‘This Tilting Earth’, which comprises five short pieces. From just three lines to a maximum of nine lines, these are sketches that suggest the whole picture, which we can find by looking up the places and creature names in the titles.

Whether it’s a tusk found at Sithylemenkat Lake in Alaska, where mammoths died and iron filings from a meterorite collision lodged in their tusks and the horns of bison, or the whole body of the best preserved woolly mammoth so far discovered, these poems draw us in to engage with the world that preceded us and also to imagine the fragility of life and the imminent risk of extinction. I’ll quote the poem about the woolly mammoth ‘Yuka’ in full:

Vulnerable Yuka,

adored from withered trunk to straggled hair

dreams skulking lions held at bay by savages with knives,

a shoreline carved from ice,

the coldest, bluest air above the Laptev Sea.

Episodes from more recent history inform other poems, including the final leap of daredevil Sam Patch, who died at the age of twenty-two jumping into the water from on high at Niagara Falls. Lovell captures the experience of the fall, when ‘He remembers, briefly, plummeting,/tilting slowly like a tree through stinging spray’ and also the transformation of the body, which takes on the characteristics of the natural surroundings: ‘Algae quietly invade his brain, bloom inside his bones’.

But it is Sam Patch’s bear which gets the final lines in the poem:

The bear, snarled in his chain,was soon forgotten;

His carcass, bitten white as willow, was never found.

The bear cub was thrown down by Sam Patch before he made his leap in 1829, and unlike his owner had no choice in the matter. In ‘The Last Leap of Sam Patch’ and in ‘Clemency for the Drayman’, Lovell draws attention to our inhumane treatment of animals for work and entertainment, and the way we forget them and forefront our own importance instead. This links the human species of ancient and more modern history, although previous human species lasted longer than we may do if we fail in our role as caretakers of the planet. They were the better custodians, as Yuval Noah Harari says in his book Sapiens.

In ‘Migrants’ we start by feeling empathy for the worker in tough conditions who spends ‘long hours ravelling and unreeling’ silk from boiled cocoons, until ‘by morning, he fills the room with coiled skeins,/mermaid hair spilling like waves/in wheaten figures of eight.’ The quality of the language and the rhythm of the lines is typical of the way Lovell gives pleasure to the reader (it’s worth reading the poems aloud to get a full sense of this). But there is also pain here, for the multiple killings involved in the production of silk, and this is reinforced by the image of caged songbirds above textile workers in the second poem in the sequence. The birds bring some joy to the migrants working in a loft, but can’t survive the conditions.

As the poems move between centuries and geographical locations, the themes and repeated words chime together in a common vocabulary, weaving the poems into a bonded whole. Birds and their plumage appear in other poems, including ‘Aigrettes, Spring 1893’, a poem that becomes cryptic as it progresses from images of the fragility and death of birds to lines such as:

you wanted the ‘Valkyrie effect’

Mercury wings, the elegance

of Mephisto aigrettes

A web search for the Valkyrie effect shows that this verse contains found lines from a catalogue of the latest fashions in 1893, which incorporated not only plumage but entire bodies of birds in the clothing. Like the clothing, the poem reveals the cruelty beneath its beauty if the reader investigates further. Among the other recurrent themes, the mistreatment of horses appears in various poems, along with striking descriptions of their beauty, so that the collection moves forward while also looking back towards the aesthetics of the Vogelherd Horse and the fear of the drayman’s horse.

‘Portraits, Samoa 1853’ has an unnamed artist or anthropologist painting the locals using the kind of equipment used by the cave painters in ‘Limousin, Lascaux’ – ‘pens whittled from pointed bones,/quills and picks of tortoiseshell’. The equipment also exploits animals, so the various themes blend together. Like the songbirds in cages, we find specimens of taxidermy in bell jars and glass cases in some poems, including ‘Galapagos’, a name that conjures up Darwin as it was so crucial to the development of his theory. Instead we find a boy devoid of sympathy to wildlife, cutting down wildlife with a stick and whip, ‘dislocating/vertebrae, unhinging the graceful heads’.‘Galapagos’ ends with the lines:

We are all in this together.

No one is watching.

The suggestion is that we are all complicit and not called to account for our damaging actions; but the poems are witness to each small and large atrocity, making us look back with the wisdom of hindsight, and then ahead with the awareness of the need for foresight so that we treat the planet and the life on it with kindness and protection.

May 17 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Jane Lovell

Poetry Review – This Tilting Earth: Adele Ward reviews Jane Lovell’s new pamphlet which is full of concern for our planet

Jane Lovell’s latest pamphlet This Tilting Earth was the winner of the prestigious Mslexia Poetry Pamphlet Competition, which leads to publication by Seren. Although it’s a short collection, the poems open themselves up to much wider vistas – especially if read alongside methods for further research. My first reading, while travelling on the tube, depended solely on the poems, but reading them a second time at home, with the possibility of online searches, was a completely different experience. Some reviewers have said notes for the poems would have helped, but perhaps the point is to tempt readers to engage in research.

Some poems, such as ‘Limousin, Lascaux’, refer to relatively familiar subjects – in this case the cave paintings – although even in this instance I enjoyed finding images online. The poem adds to our view of the paintings with a sense of colour and movement, for example in the lines:

and the creatures are given momentum, creating a meeting of lives across the millennia, including ancient and modern human lives:

This poem stands out for me, as does the opening poem ‘Song of the Vogelherd Horse’, which required an image search online and worked best with a mental picture of the minimalist sculpture of a curved horse carved from a mammoth tusk. It starts ‘I am curved air/or water over stone’, a perfect combination of metaphors for the smoothness and rounded shape of this piece of ancient art. Our connection with our early ancestors is suggested in lines such as ‘Existing in two worlds/I find footholds in moments/cast off by ice’ and also ‘I was here before your god./Cherish my broken form.’

The theme of mammoths and human interaction with these extraordinary creatures continues into the next sequence, titled like the pamphlet ‘This Tilting Earth’, which comprises five short pieces. From just three lines to a maximum of nine lines, these are sketches that suggest the whole picture, which we can find by looking up the places and creature names in the titles.

Whether it’s a tusk found at Sithylemenkat Lake in Alaska, where mammoths died and iron filings from a meterorite collision lodged in their tusks and the horns of bison, or the whole body of the best preserved woolly mammoth so far discovered, these poems draw us in to engage with the world that preceded us and also to imagine the fragility of life and the imminent risk of extinction. I’ll quote the poem about the woolly mammoth ‘Yuka’ in full:

Episodes from more recent history inform other poems, including the final leap of daredevil Sam Patch, who died at the age of twenty-two jumping into the water from on high at Niagara Falls. Lovell captures the experience of the fall, when ‘He remembers, briefly, plummeting,/tilting slowly like a tree through stinging spray’ and also the transformation of the body, which takes on the characteristics of the natural surroundings: ‘Algae quietly invade his brain, bloom inside his bones’.

But it is Sam Patch’s bear which gets the final lines in the poem:

The bear cub was thrown down by Sam Patch before he made his leap in 1829, and unlike his owner had no choice in the matter. In ‘The Last Leap of Sam Patch’ and in ‘Clemency for the Drayman’, Lovell draws attention to our inhumane treatment of animals for work and entertainment, and the way we forget them and forefront our own importance instead. This links the human species of ancient and more modern history, although previous human species lasted longer than we may do if we fail in our role as caretakers of the planet. They were the better custodians, as Yuval Noah Harari says in his book Sapiens.

In ‘Migrants’ we start by feeling empathy for the worker in tough conditions who spends ‘long hours ravelling and unreeling’ silk from boiled cocoons, until ‘by morning, he fills the room with coiled skeins,/mermaid hair spilling like waves/in wheaten figures of eight.’ The quality of the language and the rhythm of the lines is typical of the way Lovell gives pleasure to the reader (it’s worth reading the poems aloud to get a full sense of this). But there is also pain here, for the multiple killings involved in the production of silk, and this is reinforced by the image of caged songbirds above textile workers in the second poem in the sequence. The birds bring some joy to the migrants working in a loft, but can’t survive the conditions.

As the poems move between centuries and geographical locations, the themes and repeated words chime together in a common vocabulary, weaving the poems into a bonded whole. Birds and their plumage appear in other poems, including ‘Aigrettes, Spring 1893’, a poem that becomes cryptic as it progresses from images of the fragility and death of birds to lines such as:

A web search for the Valkyrie effect shows that this verse contains found lines from a catalogue of the latest fashions in 1893, which incorporated not only plumage but entire bodies of birds in the clothing. Like the clothing, the poem reveals the cruelty beneath its beauty if the reader investigates further. Among the other recurrent themes, the mistreatment of horses appears in various poems, along with striking descriptions of their beauty, so that the collection moves forward while also looking back towards the aesthetics of the Vogelherd Horse and the fear of the drayman’s horse.

‘Portraits, Samoa 1853’ has an unnamed artist or anthropologist painting the locals using the kind of equipment used by the cave painters in ‘Limousin, Lascaux’ – ‘pens whittled from pointed bones,/quills and picks of tortoiseshell’. The equipment also exploits animals, so the various themes blend together. Like the songbirds in cages, we find specimens of taxidermy in bell jars and glass cases in some poems, including ‘Galapagos’, a name that conjures up Darwin as it was so crucial to the development of his theory. Instead we find a boy devoid of sympathy to wildlife, cutting down wildlife with a stick and whip, ‘dislocating/vertebrae, unhinging the graceful heads’.‘Galapagos’ ends with the lines:

The suggestion is that we are all complicit and not called to account for our damaging actions; but the poems are witness to each small and large atrocity, making us look back with the wisdom of hindsight, and then ahead with the awareness of the need for foresight so that we treat the planet and the life on it with kindness and protection.