Poetry review – Visiting Hours: Carla Scarano is captivated by the magical quest elements in a new collection from Kitty Coles

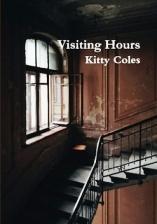

Visiting Hours

Kitty Coles

The High Window

ISBN 9781913201159

£ 10

Visiting Hours

Kitty Coles

The High Window

ISBN 9781913201159

£ 10

Kitty Coles’s debut collection opens up to the uncanny wonders of an interior world (or an underworld) secret and unsettling, which unfold poem after poem. The reader is introduced to the five sections by titles, such as “A fracture in Plaster” or “The Placement of Your Bones”. These guide the reader through a maze-like process by which the poet understands and communicates her thoughts. It is an uncanny, disquieting reality that connects to Gothic literature and to Freud’s ‘strangely familiar’, that is, it is both frightful and attractive. These elements are also present in Coles’s first pamphlet, Seal Wife (Indigo Pamphlets, 2017), but in this collection there is a further development both in content and form.

As she states in the first poem, ‘there is something lost that can be found’ (“Tomato Soup Cake”); it is the unfamiliar that is hidden under ordinary life and needs to be revealed to attain a better understanding of the world and of the self. Mirror images, magic and references to the world of fairy tales are all involved in this process, which is a quest in the untracked world of dreams which often overlaps with everyday reality. The poems portray a world of hopes and wishes that sometimes clashes with ordinary life but also uncovers what we have temporarily forgotten or repressed, thus bringing to the surface something that might seem negative but that is part of us and reveals (maybe against our will) a secret side. It is an intriguing quest that unveils and hides at the same time, exposing an apparently dark aspect which is fearsome and tempting and is inevitably part of our being. The poems explore this both inside the house and outside, in everyday life with particular consideration for the mental health environment where the author works.

To give a flavour of the poems here are lines from “I am Bringing You My Heart in a Small Box”

… studded with pins, a hoodoo artefact,

hot from the burning hob, the rendered tallow.

Here are my fingernails, narrow moon-shavings,

and a slice of yellow hair, like a slice of sun.

This is my spit, willingly given to you,

for you to wrap my soul in a mesh of air.

Magic is evoked, but the main concern of the poet is to be involved in exploring an interior world but starting from the outside and from the practical and visible. This is an apparently safe world but it is dangerously menaced by floods and landslides:

The water lifted stone and threw it back,

milling it fine; the air was grained with it.

The water left us glass and dirtless shells

and once a funeral wreath,

bleeding its purples.

Now cliffs return to dust and houses

Slant. Walls rubble up and fences

travel seawards.

(“Erosion”)

.

We barely noticed at first:

a fracture in the plaster, thin as a hair,

then other fractures leading off from it,

veining the walls like rivers,

a map of blemish, the stealthy scent

of loam, a sound of beetles there

behind the skirting, of breathing in and out

below the floor.

(“Encroachment”)

.

We are presented with an eroded apocalyptic vision with fractures that hide dangerous creatures and where we are menaced by the consequences of global warming. However, this is also a place that needs to be explored and understood, revealed and acknowledged at the same time. The poems build up suspense that expresses the fears and pleasures of encounters with the uncanny. The poet expands this concept with the skilful use of line breaks, alliterations and, in some poems, repetitions. These techniques communicate the content in a pressing broken rhythm that engages the reader:

At the full moon,

I hear his long nails scratching

against the doorframe,

and his quiet whine,

its syllables

his rough approximation,

his lupine effort,

to pronounce my name.

…

He stands on his hind legs,

like a man,

coat thick and bloody.

His jaws drip freely

with their offering.

What is that gift he holds,

where did he find it,

why must I take it in my gooseflesh hands?

(“The Wolf at the Door”)

The fearful challenge implies a promise and a ‘gift’, an ‘offering’ the man-wolf brings, maybe a revelation that needs to be uncovered. Therefore, fears are part being alive – and this encompasses death as well, an underworld that is often neglected but that is a necessary part of being human. The poet’s mapping of the body and of the mind brings us to unfamiliar paths bravely explored and described with unexpected connections and compelling imageries:

She clopped downstairs, that CPN,

her heels very unreverentially chopping

the yeasty air to bits,

her dress a hothouse clangour in the stillness,

announcing breathily to me and others,

‘Schizophrenia my arse: he wants attention’.

Her words hung pearl-like,

shining and globular,

(“The CPN”)

The poem “Posing as Ophelia”, which was nominated for the Forward Prize, is a brilliant re-visitation of Ophelia’s role:

… I was

an inapt pupil and forgot

distracted when he told me

to speak softer, to lose

myself in the petals in my hands. Flakes brighten

under my eyelids, build

me pictures. I feel myself dissolve,

poor sugarmouse; I feel my blood lulling

itself to stillness.

(“Posing as Ophelia’)

.

The tone is ironic, mocking the patronising male voice that tries to manipulate not only the sitter’s position but also her thoughts. This re-writes the myth of the lost-in-love poor Ophelia and allows the girl to voice her thoughts. It connects to the last poem of the second section, “Keep Away from Fire”, where the daring thoughts of Ophelia and the poet’s quest are considered dangerous and therefore subject to punishment or ‘purification’ through fire:

Be safe and cold.

Avoid the fate of the witch,

The moth, the martyr.

Stand back

from the scarlet heart;

The poet seems to trace the destiny of rebellious women who wish to know more and are searching for self-knowledge and power. Such women were considered outsiders and therefore punished. There is also a connection to the theme of the double, who is also a woman.. This is consistent with the uncanny that is explored throughout the collection:

There has always been another woman inside me,

a small one who wears this flesh of mine

like a coat, hiding her pure self in the folds

of my flesh, the plenitude of thighs,

ripeness of belly.

Now her murmurs grow louder.

The house is filled with her keening.

(“The Thin Woman”)

The double or doppelganger might be the dark side the poet is investigating, frightful and appealing at the same time – something that is both gift and curse, with a promise of alternative knowledge and thorough understanding. But the search is never concluded because the attempt to connect the inside and outside worlds also envisages a division:

When our hands grip like magnets,

snug and hot, I think

their dampness is a seal, a promise.

My nails indent you. Then the furrows fade

and we are separate, though

we press and press

and strain our fingers

at the edge of faith.

(“The Division”)

There is a consistent development of themes in this collection, which makes it accessible and enthralling. Rather like a phoenix, the poet stands ‘among the ash’ in the last poem, ready to be reborn, but not yet. The process is unending, going on as it needs more exploration, more analysis. Maybe it is also suggested that resurrection does not belong to this world. We are only allowed to carry on with our search without finding one final goal, or perhaps finding different endings in different times of our life. Such are the options available in our unpredictable world.

Mar 9 2020

London Grip Poetry Review – Kitty Coles

Poetry review – Visiting Hours: Carla Scarano is captivated by the magical quest elements in a new collection from Kitty Coles

Kitty Coles’s debut collection opens up to the uncanny wonders of an interior world (or an underworld) secret and unsettling, which unfold poem after poem. The reader is introduced to the five sections by titles, such as “A fracture in Plaster” or “The Placement of Your Bones”. These guide the reader through a maze-like process by which the poet understands and communicates her thoughts. It is an uncanny, disquieting reality that connects to Gothic literature and to Freud’s ‘strangely familiar’, that is, it is both frightful and attractive. These elements are also present in Coles’s first pamphlet, Seal Wife (Indigo Pamphlets, 2017), but in this collection there is a further development both in content and form.

As she states in the first poem, ‘there is something lost that can be found’ (“Tomato Soup Cake”); it is the unfamiliar that is hidden under ordinary life and needs to be revealed to attain a better understanding of the world and of the self. Mirror images, magic and references to the world of fairy tales are all involved in this process, which is a quest in the untracked world of dreams which often overlaps with everyday reality. The poems portray a world of hopes and wishes that sometimes clashes with ordinary life but also uncovers what we have temporarily forgotten or repressed, thus bringing to the surface something that might seem negative but that is part of us and reveals (maybe against our will) a secret side. It is an intriguing quest that unveils and hides at the same time, exposing an apparently dark aspect which is fearsome and tempting and is inevitably part of our being. The poems explore this both inside the house and outside, in everyday life with particular consideration for the mental health environment where the author works.

To give a flavour of the poems here are lines from “I am Bringing You My Heart in a Small Box”

Magic is evoked, but the main concern of the poet is to be involved in exploring an interior world but starting from the outside and from the practical and visible. This is an apparently safe world but it is dangerously menaced by floods and landslides:

The water lifted stone and threw it back, milling it fine; the air was grained with it. The water left us glass and dirtless shells and once a funeral wreath, bleeding its purples. Now cliffs return to dust and houses Slant. Walls rubble up and fences travel seawards. (“Erosion”) . We barely noticed at first: a fracture in the plaster, thin as a hair, then other fractures leading off from it, veining the walls like rivers, a map of blemish, the stealthy scent of loam, a sound of beetles there behind the skirting, of breathing in and out below the floor. (“Encroachment”) .We are presented with an eroded apocalyptic vision with fractures that hide dangerous creatures and where we are menaced by the consequences of global warming. However, this is also a place that needs to be explored and understood, revealed and acknowledged at the same time. The poems build up suspense that expresses the fears and pleasures of encounters with the uncanny. The poet expands this concept with the skilful use of line breaks, alliterations and, in some poems, repetitions. These techniques communicate the content in a pressing broken rhythm that engages the reader:

At the full moon, I hear his long nails scratching against the doorframe, and his quiet whine, its syllables his rough approximation, his lupine effort, to pronounce my name. … He stands on his hind legs, like a man, coat thick and bloody. His jaws drip freely with their offering. What is that gift he holds, where did he find it, why must I take it in my gooseflesh hands? (“The Wolf at the Door”)The fearful challenge implies a promise and a ‘gift’, an ‘offering’ the man-wolf brings, maybe a revelation that needs to be uncovered. Therefore, fears are part being alive – and this encompasses death as well, an underworld that is often neglected but that is a necessary part of being human. The poet’s mapping of the body and of the mind brings us to unfamiliar paths bravely explored and described with unexpected connections and compelling imageries:

She clopped downstairs, that CPN, her heels very unreverentially chopping the yeasty air to bits, her dress a hothouse clangour in the stillness, announcing breathily to me and others, ‘Schizophrenia my arse: he wants attention’. Her words hung pearl-like, shining and globular, (“The CPN”)The poem “Posing as Ophelia”, which was nominated for the Forward Prize, is a brilliant re-visitation of Ophelia’s role:

… I was an inapt pupil and forgot distracted when he told me to speak softer, to lose myself in the petals in my hands. Flakes brighten under my eyelids, build me pictures. I feel myself dissolve, poor sugarmouse; I feel my blood lulling itself to stillness. (“Posing as Ophelia’) .The tone is ironic, mocking the patronising male voice that tries to manipulate not only the sitter’s position but also her thoughts. This re-writes the myth of the lost-in-love poor Ophelia and allows the girl to voice her thoughts. It connects to the last poem of the second section, “Keep Away from Fire”, where the daring thoughts of Ophelia and the poet’s quest are considered dangerous and therefore subject to punishment or ‘purification’ through fire:

The poet seems to trace the destiny of rebellious women who wish to know more and are searching for self-knowledge and power. Such women were considered outsiders and therefore punished. There is also a connection to the theme of the double, who is also a woman.. This is consistent with the uncanny that is explored throughout the collection:

There has always been another woman inside me, a small one who wears this flesh of mine like a coat, hiding her pure self in the folds of my flesh, the plenitude of thighs, ripeness of belly. Now her murmurs grow louder. The house is filled with her keening. (“The Thin Woman”)The double or doppelganger might be the dark side the poet is investigating, frightful and appealing at the same time – something that is both gift and curse, with a promise of alternative knowledge and thorough understanding. But the search is never concluded because the attempt to connect the inside and outside worlds also envisages a division:

When our hands grip like magnets, snug and hot, I think their dampness is a seal, a promise. My nails indent you. Then the furrows fade and we are separate, though we press and press and strain our fingers at the edge of faith. (“The Division”)There is a consistent development of themes in this collection, which makes it accessible and enthralling. Rather like a phoenix, the poet stands ‘among the ash’ in the last poem, ready to be reborn, but not yet. The process is unending, going on as it needs more exploration, more analysis. Maybe it is also suggested that resurrection does not belong to this world. We are only allowed to carry on with our search without finding one final goal, or perhaps finding different endings in different times of our life. Such are the options available in our unpredictable world.