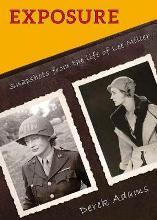

Poetry Review – Exposure. Stephen Claughton reviews a collection by Derek Adams which sharply captures key moments in the life of photographer Lee Miller

Exposure

Derek Adams

Dempsey & Windle

ISBN 978-1-907435-94-2

£8.00

Exposure

Derek Adams

Dempsey & Windle

ISBN 978-1-907435-94-2

£8.00

Ironically, Lee Miller’s most famous photograph wasn’t one of hers, but instead was taken by David Sherman. It shows her sitting in Hitler’s bath, the Führer’s picture propped on the sill behind and her muddy boots in front on the floor, or as Derek Adams dramatically puts it:

her great army boots on the floor,

dirt from Dachau

stamped into the rug.

But then, Miller began her career as a model rather than a photographer. Adams’ Exposure — subtitled “Snapshots from the Life of Lee Miller” — tracks the girl from Poughkeepsie from abused child, to cover girl, photographer, war correspondent and alcoholic. Following years of neglect, her photographs were rediscovered only after her death:

In the dust-dry dark

of the attic, hived

in cardboard boxes

as the opening poem, “Farley Farm”, says. She was also a mistress and muse, first living with Man Ray, then married to an Egyptian businessman and finally to Roland Penrose, as well as being one of Picasso’s lovers. Adams has previously written a sequence of poems, unconcerned but not indifferent, about Man Ray and four of the poems from that 2006 pamphlet reappear here.

Miller’s story is told in short, punchy poems from various angles in a variety of voices. It was the pre-digital age, when the camera could still be regarded as an innocent eye: ‘twelve exposures on a roll — / trap the pure moment / then wind on to the next’ (“Rolleiflex”). This is particularly effective in poems about her childhood. ‘Through seven-year-old eyes, / everything is strange in this strange town,’ Adams says of her being taken to New York, while her mother was in hospital. Unfortunately, her innocence exposed her to abuse. The following poem, “Jolly Jack”, begins:

Away from home for the first time,

alone among strangers

who act like they know you

and ends:

Alone with you he acts strange,

holds your head to kiss you,

his tongue foreign in your mouth.

No wonder the child is confused: good and bad people both say the same things. In “Afterwards”, it’s revealed that the abuser has given her a sexually-transmitted disease:

Afterwards he cries and hugs you,

tells you he loves you,

tells you that no one must know.

Home in Poughkeepsie

the doctor shakes his head,

delivers his hush-toned diagnosis.

Afterwards, Mama cries and hugs you,

tell you she loves you.

tells you that no one must know.

Then there is Miller’s own father photographing his young daughter outside in the snow:

I think about going indoors,

putting all my clothes back on,

the hot chocolate Papa has promised.

Giving his photograph the arty title of “December Morn” is no more convincing an excuse than the same man’s experiments with stereoscopy involving the adult Miller (‘I disrobe and he poses me’):

We all marvel at the effect, so lifelike

you could reach out and touch my body.

(“Aesthetic”)

Rather than be a victim, Miller takes charge of her life, first by pretending to step out into the New York traffic, so that she can be ‘saved’ by Condé Nast (‘chance, possibly, like a young man / snared by a dropped glove’), who then puts her on the cover of his magazine, Vogue, where:

knowing predator eyes

stare out at the future, bright

as a candle burning at both ends.

Later, she goes in pursuit of Man Ray (‘I chase after him all over Paris’, ‘I chase after him to Biarritz’). Her move from in front of the camera to behind it was another way of taking control:

In the square, ground glass viewfinder

I have found the ideal tool

to frame and order my world.

(“Rolleiflex”)

Adams is himself a professional photographer and has an interest in the experimental techniques that Miller developed with Man Ray. Unlike her father’s dubious experiments with stereoscopy, their discoveries are accidental. “Sabbatier Effect” and “Solarisation”, both achieved by re-exposure or over-exposure in the darkroom, are surreal effects, though they can hardly be more surreal than Miller’s photographing, in Vogue’s Paris studio, the severed breast from a radical mastectomy, which she has carried in on a covered plate (“Untitled”).

She and Man Ray clearly had a stormy relationship:

I say ‘Fuck off little Man

my body is my own to please who I please’.

He slaps my face, I scratch his cheek.

He roars and throws me to our bed,

I kick and bite, we roll around,

he holds me down, the sex is great.

(“Bal Blanc”)

But the Bohemian couple seem almost conventional, when in “Babysitting for the Seabrooks” they unpadlock the woman that occultist William Seabrook keeps as a sex-slave and instead of feeding her ‘as you would a dog’, have her dine with them, chaining her up again only at the end of the evening, before the Seabrooks return, when ‘We place a plate of leftovers on the floor.’

The Second World War is covered by just four poems (“Grim Glory” and “Remington Silent” about the Blitz, “Angora” about Dachau and “Lee at War” which includes the photo in Hitler’s bath). More space is given to the “Aftermath”, as one of the poems is titled: Miller’s marriage to Roland Penrose, motherhood and retirement to Farley Farm in Sussex. It could have been a rural idyll, but instead marked her descent into alcoholism. It was perhaps inevitable that going through the war would finally expose the fragility that underlay her tough persona, given her earlier experiences — not only abuse, but seeing her boyfriend drown in a boating accident (“Not a Wave”). Exposure ends with “The Long Man”, in which the Wilmington Giant chalk figure (the one with two staves like a Nordic walker) — visible from Farley Farm, a note tells us, between the spring and autumn equinox — becomes an image of childhood trauma:

A giant figure overlooking my life

it seems he has been there forever,

dominating from a distance,

hidden in the mist,

appearing and disappearing

with the seasons.

It is a mark of Derek Adams’ skill that he has been able to convey so much about Miller’s varied life in such a short space. These are spare, unflashy poems that often depend on repetition for their effect, whether full-on anaphora as in “Mistress of l’image trouvé” or “Aftermath”, or more subtly as in “Intersection” or “Meeting Man Ray”. The effect is that of building up a picture by means of multiple shots, explicitly so in “Picnic”:

Lee picks up her Rolleiflex

releases the shutter:

click — seals the moment

click — Paul kisses Nusch

click — Roland rolls his eyes

click — Man smiles self consciously

click — Ady grins, teeth ironing board wide

against coffee and cream skin

click — beyond the distant trees,

uniform grey shadows gather.

(The significance of the last line is clear from the dateline: Mougins, 1937.) In the end, it’s all about selection — the angle, framing, focus and, yes, exposure.

Nov 27 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Derek Adams

Poetry Review – Exposure. Stephen Claughton reviews a collection by Derek Adams which sharply captures key moments in the life of photographer Lee Miller

Ironically, Lee Miller’s most famous photograph wasn’t one of hers, but instead was taken by David Sherman. It shows her sitting in Hitler’s bath, the Führer’s picture propped on the sill behind and her muddy boots in front on the floor, or as Derek Adams dramatically puts it:

But then, Miller began her career as a model rather than a photographer. Adams’ Exposure — subtitled “Snapshots from the Life of Lee Miller” — tracks the girl from Poughkeepsie from abused child, to cover girl, photographer, war correspondent and alcoholic. Following years of neglect, her photographs were rediscovered only after her death:

as the opening poem, “Farley Farm”, says. She was also a mistress and muse, first living with Man Ray, then married to an Egyptian businessman and finally to Roland Penrose, as well as being one of Picasso’s lovers. Adams has previously written a sequence of poems, unconcerned but not indifferent, about Man Ray and four of the poems from that 2006 pamphlet reappear here.

Miller’s story is told in short, punchy poems from various angles in a variety of voices. It was the pre-digital age, when the camera could still be regarded as an innocent eye: ‘twelve exposures on a roll — / trap the pure moment / then wind on to the next’ (“Rolleiflex”). This is particularly effective in poems about her childhood. ‘Through seven-year-old eyes, / everything is strange in this strange town,’ Adams says of her being taken to New York, while her mother was in hospital. Unfortunately, her innocence exposed her to abuse. The following poem, “Jolly Jack”, begins:

and ends:

No wonder the child is confused: good and bad people both say the same things. In “Afterwards”, it’s revealed that the abuser has given her a sexually-transmitted disease:

Then there is Miller’s own father photographing his young daughter outside in the snow:

Giving his photograph the arty title of “December Morn” is no more convincing an excuse than the same man’s experiments with stereoscopy involving the adult Miller (‘I disrobe and he poses me’):

Rather than be a victim, Miller takes charge of her life, first by pretending to step out into the New York traffic, so that she can be ‘saved’ by Condé Nast (‘chance, possibly, like a young man / snared by a dropped glove’), who then puts her on the cover of his magazine, Vogue, where:

Later, she goes in pursuit of Man Ray (‘I chase after him all over Paris’, ‘I chase after him to Biarritz’). Her move from in front of the camera to behind it was another way of taking control:

Adams is himself a professional photographer and has an interest in the experimental techniques that Miller developed with Man Ray. Unlike her father’s dubious experiments with stereoscopy, their discoveries are accidental. “Sabbatier Effect” and “Solarisation”, both achieved by re-exposure or over-exposure in the darkroom, are surreal effects, though they can hardly be more surreal than Miller’s photographing, in Vogue’s Paris studio, the severed breast from a radical mastectomy, which she has carried in on a covered plate (“Untitled”).

She and Man Ray clearly had a stormy relationship:

But the Bohemian couple seem almost conventional, when in “Babysitting for the Seabrooks” they unpadlock the woman that occultist William Seabrook keeps as a sex-slave and instead of feeding her ‘as you would a dog’, have her dine with them, chaining her up again only at the end of the evening, before the Seabrooks return, when ‘We place a plate of leftovers on the floor.’

The Second World War is covered by just four poems (“Grim Glory” and “Remington Silent” about the Blitz, “Angora” about Dachau and “Lee at War” which includes the photo in Hitler’s bath). More space is given to the “Aftermath”, as one of the poems is titled: Miller’s marriage to Roland Penrose, motherhood and retirement to Farley Farm in Sussex. It could have been a rural idyll, but instead marked her descent into alcoholism. It was perhaps inevitable that going through the war would finally expose the fragility that underlay her tough persona, given her earlier experiences — not only abuse, but seeing her boyfriend drown in a boating accident (“Not a Wave”). Exposure ends with “The Long Man”, in which the Wilmington Giant chalk figure (the one with two staves like a Nordic walker) — visible from Farley Farm, a note tells us, between the spring and autumn equinox — becomes an image of childhood trauma:

It is a mark of Derek Adams’ skill that he has been able to convey so much about Miller’s varied life in such a short space. These are spare, unflashy poems that often depend on repetition for their effect, whether full-on anaphora as in “Mistress of l’image trouvé” or “Aftermath”, or more subtly as in “Intersection” or “Meeting Man Ray”. The effect is that of building up a picture by means of multiple shots, explicitly so in “Picnic”:

(The significance of the last line is clear from the dateline: Mougins, 1937.) In the end, it’s all about selection — the angle, framing, focus and, yes, exposure.