Peter Ualrig Kennedy recommends an epic and heartbreaking poem, beautifully translated from the Dutch of Guus Luijters

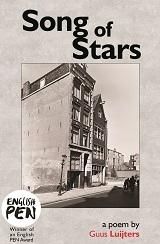

Song of Stars

Guus Luijters; translator Marian de Vooght

Smokestack Books

ISBN 978-1-9998276-7-0

140pp £8.99

Song of Stars

Guus Luijters; translator Marian de Vooght

Smokestack Books

ISBN 978-1-9998276-7-0

140pp £8.99

We deal here with a poem which constitutes an impressive and powerful book by the writer and poet Guus Luijters. It has been magisterially translated into English by Marian de Vooght, who brings Sientje Abram’s story to life for us. The translator is hugely deserving of the English PEN award which the book received in 2018. I think ‘Song of Stars’ should be made compulsory reading in schools throughout the land.

‘Song of Stars (Sterrenlied)’ – referring of course to the Star of David – is presented with the Dutch text on the left hand page, and the English translation opposite. I do not speak Dutch, but I found that by reading visually through the Dutch original I began to recognise words by their concordance with their English counterpart. Such concordance, from their shared roots, is symbolic of our own shared links between the Netherlands and Britain; we are each European. I have also had the privilege of hearing Marian de Vooght give a reading of the poem in both Dutch and English. The translator is exemplary in her reproduction of the line form and the cadence of the original.

The poem consists in a dialogue between the interlocutor – Guus Luijters – and eleven year-old Sientje Abram from a small street in Jewish Amsterdam. This little girl’s life ended in Birkenau; unlike Anne Frank she left no written records, and almost nothing is known about her apart from some details of her house and her family, which Luijters provides in an After-word. But the poet has succeeded in giving her a life by means of this poetic dialogue, and so imparting to Sientje some degree of immortality.

Luijters and his splendid translator de Vooght write a spare,cut back poetry which is alive and vital in its stream of consciousness. It is written in the alternating voices of the interlocutor and the girl, and it moves Sientje ineluctably forward from a quotidian life in her street and in her school towards the final end, evoking the machine of oppression which is powerful and inescapable; the words and chapters march on, they are the slow beat of a pulse, or of a clock marking the seconds and minutes of a life. They are spellbinding. Words spill over from line to line, there is a constant enjambment which leaves us breathless:

Every morning I greet

all things the table

hi table the clock and the

rug I wash myself at the

tap in the kitchen by the

window I name the moon

too hi I say hi moon

And from this quiet daily routine the inexorable words of the poem take us very soon into an atmosphere of foreboding:

It’s always silent in the street

and it seems forever summer

with its white stripes in the sky

like quiet trams taken

to the depot it is

night you hear the grinding

of the switches in the rails

In the poem there are only a few references to Jews and Judaism. The narration is eloquent in its understatement. The little girl does not understand:

My brother says we’re Jews

what Jews are he doesn’t

want to say but they eat

chicken soup and have

Shabbos on Shabbos so we

are Jews what does my

brother mean by that

The family waits in the house:

We sit inside and we

wait my little suitcase

packed I wrote my name

on it and the city

Sientje Abram Amsterdam

I know I’m going on a journey

where to I do not want to know

The simplicity of this writing, and the tumbling lack of punctuation, impart the immediacy of a child’s thoughts. Throughout the progress of the eleven chapters, Sientje’s verses become fewer and fewer compared to the interlocutor’s – her time is shrinking. We know that as the train moves on and as the implacable verses move on and on, the finality of extermination of a child and of a people is just around the corner. The ending stanzas are heartbreaking:

We have left and won’t

come back my father my mother

my brothers and thousands of others

loaded onto a train we have been

deported I didn’t wave goodbye

I didn’t look back

I’ve left and won’t come back

Sientje has left her home for ever, and she has left Guus Luijters, but he has given this one girl her name and her immortality.

The poem at that point is not quite complete: there comes the prosaicness of “A tourist does Birkenau” but “in the wind that rages / across the frozen plain / he hears the names of the dead / the names of the children / from Rapenburger Street who / just like Sientje were murdered” and there follow ten – yes ten – pages of the names of those 331 children from Rapenburger Street. The very last line of all comes with its chilling finality:

all of them murdered

I recommend to you this moving story, this epic poem, beautifully translated by Marian de Vooght. The postscript to the poem is the Afterword in which Guus Luijters describes Sientje and her family, and the train with its “930 involuntary passengers” on the journey which ended in the gas chambers of Birkenau. Luijters underlines for us the Nazi bureaucracy which kept notes and lists of names and occupations – the banality of evil (Hannah Arendt). On the last page of the book Luijters writes “That is all that I found out about Sientje Abram.”

One child. One street. One town. One country. One people.

Apr 30 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Guus Luijters

Peter Ualrig Kennedy recommends an epic and heartbreaking poem, beautifully translated from the Dutch of Guus Luijters

We deal here with a poem which constitutes an impressive and powerful book by the writer and poet Guus Luijters. It has been magisterially translated into English by Marian de Vooght, who brings Sientje Abram’s story to life for us. The translator is hugely deserving of the English PEN award which the book received in 2018. I think ‘Song of Stars’ should be made compulsory reading in schools throughout the land.

‘Song of Stars (Sterrenlied)’ – referring of course to the Star of David – is presented with the Dutch text on the left hand page, and the English translation opposite. I do not speak Dutch, but I found that by reading visually through the Dutch original I began to recognise words by their concordance with their English counterpart. Such concordance, from their shared roots, is symbolic of our own shared links between the Netherlands and Britain; we are each European. I have also had the privilege of hearing Marian de Vooght give a reading of the poem in both Dutch and English. The translator is exemplary in her reproduction of the line form and the cadence of the original.

The poem consists in a dialogue between the interlocutor – Guus Luijters – and eleven year-old Sientje Abram from a small street in Jewish Amsterdam. This little girl’s life ended in Birkenau; unlike Anne Frank she left no written records, and almost nothing is known about her apart from some details of her house and her family, which Luijters provides in an After-word. But the poet has succeeded in giving her a life by means of this poetic dialogue, and so imparting to Sientje some degree of immortality.

Luijters and his splendid translator de Vooght write a spare,cut back poetry which is alive and vital in its stream of consciousness. It is written in the alternating voices of the interlocutor and the girl, and it moves Sientje ineluctably forward from a quotidian life in her street and in her school towards the final end, evoking the machine of oppression which is powerful and inescapable; the words and chapters march on, they are the slow beat of a pulse, or of a clock marking the seconds and minutes of a life. They are spellbinding. Words spill over from line to line, there is a constant enjambment which leaves us breathless:

And from this quiet daily routine the inexorable words of the poem take us very soon into an atmosphere of foreboding:

In the poem there are only a few references to Jews and Judaism. The narration is eloquent in its understatement. The little girl does not understand:

The family waits in the house:

The simplicity of this writing, and the tumbling lack of punctuation, impart the immediacy of a child’s thoughts. Throughout the progress of the eleven chapters, Sientje’s verses become fewer and fewer compared to the interlocutor’s – her time is shrinking. We know that as the train moves on and as the implacable verses move on and on, the finality of extermination of a child and of a people is just around the corner. The ending stanzas are heartbreaking:

Sientje has left her home for ever, and she has left Guus Luijters, but he has given this one girl her name and her immortality.

The poem at that point is not quite complete: there comes the prosaicness of “A tourist does Birkenau” but “in the wind that rages / across the frozen plain / he hears the names of the dead / the names of the children / from Rapenburger Street who / just like Sientje were murdered” and there follow ten – yes ten – pages of the names of those 331 children from Rapenburger Street. The very last line of all comes with its chilling finality:

I recommend to you this moving story, this epic poem, beautifully translated by Marian de Vooght. The postscript to the poem is the Afterword in which Guus Luijters describes Sientje and her family, and the train with its “930 involuntary passengers” on the journey which ended in the gas chambers of Birkenau. Luijters underlines for us the Nazi bureaucracy which kept notes and lists of names and occupations – the banality of evil (Hannah Arendt). On the last page of the book Luijters writes “That is all that I found out about Sientje Abram.”

One child. One street. One town. One country. One people.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, Peter Ualrig Kennedy, poetry