Mat Riches discovers there is something magical about Mike Barlow’s latest pamphlet

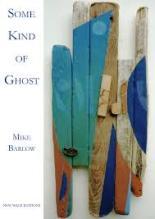

Some Kind of Ghost

Mike Barlow

New Walk Editions

ISBN 978-1-9998026-5-3

28pp £5

Some Kind of Ghost

Mike Barlow

New Walk Editions

ISBN 978-1-9998026-5-3

28pp £5

At first glance, Some Kind of Ghost is just that: a series of ghost stories about dying relationships, and missing people. In particular it features dead fathers, both biological and their imagined replacements, for example in the excellently titled, “I explain to my long dead father how poetry is less authentic than dreaming” or “The man who was not my father”.

However, while this collection is indeed filled with ghosts, it’s largely a collection of displacement and separation. In the second poem, we see a quite literal act of separation come into play in “The Stump Cross System” where the poem has us spelunking deep underground, ‘Down in the lower levels, / way beneath the show cave…’ These are the first two lines of the poem and the first line rather marvelously mimics the act of descent with its use of a dactyl and two trochees, like going down steps.

Taking a step back, we can see that the displacement activity is there from the start in the form of nervous hands in “The Secret Life of Hands” and its talk of ‘jiggling keys’, ‘fingering loose change’, ‘paradiddle(s) on the table top’ and a ‘self-manicure / during a pep-talk from the boss’. The hands of the protagonist are separated from their body, ‘Someone else, it seems, is pulling their strings’. That ‘it seems’ is yet another displacement, or a sleight of hand to distract us from the real issue at play here – the nervousness of the central character.

And, in what I hope is a deliberate act of symmetry, this sleight of hand and use of hands is echoed in the final poem, “Plums” where we’re told

Believe me, it only takes a sound, the workhorse

rhythm of diesel, say, bringing to mind

an old Fordson in a years-ago yard and before I know it

I’m up the garden path…

It’s this ‘Believe me…’ that’s crucial. It feels innocuous at first, but later in the poem as we reach the conclusion, we’re told that a relative of the central character knows them to be in the business of making things up.

She’d always ignore me when she knew

I was making things up but this time she turns,

hands me a bowl of glistening Victorias to stone.

When the poet writes ‘She’d always ignore me when she knew / I was making things up…’ it sends the reader scurrying straight back to the start of the poem (possibly even the start of the book) and that ‘Believe me’. Is this a shaggy dog story, do we believe the writer? Should we believe anything that has gone before? Should we believe the whole book? Is this the author cutting themselves off further?

This poem also completes the circle by bringing us back to the first person, after a long section where the acts of separation and displacement are amplified by a switch to the third person, following early poems that are written largely in the first. And it’s this switch that allows us to look at the world from the other side of the mirror.

In the first section, the mirror is largely being held up to the narrator’s face. In this second half, it’s held up to the world, for example in “The House on the Border”, the penultimate poem, with its evocation of a place long abandoned by many types of folks all living on the periphery of society: ‘farmers, rustler, smugglers, squatters’. The poem also asks those of us in the present to

…spare (us) a thought

for the chased off – having to live new lives somewhere

borderless, nothing to let us know which side we’re on.

We see more examples of the borderless and the separated, particularly in “The Leper’s Door”,

From the shelf inside the door, we’ll pick up whatever you offer –

food, old clothes, messages from family – then slip away,

wraithes, imagine the sacraments tang on our tongue

It’s the messages from family that feel most poignant here, although it’s also worth noting the bonus ghost in the form of the sacrament on their tongues.

Mike Barlow and New Walk Editions have crafted a pamphlet containing poems that absolutely ‘have a deceptive ease and informality’ about them as the back-cover blurb tells us. It’s this ‘deceptive’ in the blurb that rings the truest to my mind. I’m more than happy to have followed the flight of Barlow’s hands while he conjures magic in front of my very eyes. It’s not the ghosts we need to be afraid of here, it’s the living.

Feb 16 2019

London Grip Poetry Review – Mike Barlow

Mat Riches discovers there is something magical about Mike Barlow’s latest pamphlet

At first glance, Some Kind of Ghost is just that: a series of ghost stories about dying relationships, and missing people. In particular it features dead fathers, both biological and their imagined replacements, for example in the excellently titled, “I explain to my long dead father how poetry is less authentic than dreaming” or “The man who was not my father”.

However, while this collection is indeed filled with ghosts, it’s largely a collection of displacement and separation. In the second poem, we see a quite literal act of separation come into play in “The Stump Cross System” where the poem has us spelunking deep underground, ‘Down in the lower levels, / way beneath the show cave…’ These are the first two lines of the poem and the first line rather marvelously mimics the act of descent with its use of a dactyl and two trochees, like going down steps.

Taking a step back, we can see that the displacement activity is there from the start in the form of nervous hands in “The Secret Life of Hands” and its talk of ‘jiggling keys’, ‘fingering loose change’, ‘paradiddle(s) on the table top’ and a ‘self-manicure / during a pep-talk from the boss’. The hands of the protagonist are separated from their body, ‘Someone else, it seems, is pulling their strings’. That ‘it seems’ is yet another displacement, or a sleight of hand to distract us from the real issue at play here – the nervousness of the central character.

And, in what I hope is a deliberate act of symmetry, this sleight of hand and use of hands is echoed in the final poem, “Plums” where we’re told

It’s this ‘Believe me…’ that’s crucial. It feels innocuous at first, but later in the poem as we reach the conclusion, we’re told that a relative of the central character knows them to be in the business of making things up.

When the poet writes ‘She’d always ignore me when she knew / I was making things up…’ it sends the reader scurrying straight back to the start of the poem (possibly even the start of the book) and that ‘Believe me’. Is this a shaggy dog story, do we believe the writer? Should we believe anything that has gone before? Should we believe the whole book? Is this the author cutting themselves off further?

This poem also completes the circle by bringing us back to the first person, after a long section where the acts of separation and displacement are amplified by a switch to the third person, following early poems that are written largely in the first. And it’s this switch that allows us to look at the world from the other side of the mirror.

In the first section, the mirror is largely being held up to the narrator’s face. In this second half, it’s held up to the world, for example in “The House on the Border”, the penultimate poem, with its evocation of a place long abandoned by many types of folks all living on the periphery of society: ‘farmers, rustler, smugglers, squatters’. The poem also asks those of us in the present to

We see more examples of the borderless and the separated, particularly in “The Leper’s Door”,

It’s the messages from family that feel most poignant here, although it’s also worth noting the bonus ghost in the form of the sacrament on their tongues.

Mike Barlow and New Walk Editions have crafted a pamphlet containing poems that absolutely ‘have a deceptive ease and informality’ about them as the back-cover blurb tells us. It’s this ‘deceptive’ in the blurb that rings the truest to my mind. I’m more than happy to have followed the flight of Barlow’s hands while he conjures magic in front of my very eyes. It’s not the ghosts we need to be afraid of here, it’s the living.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2019 0 • Tags: books, Mat Riches, poetry