Neil Fulwood compliments Deborah Alma for a collection which rolls up its sleeves and gets down to business

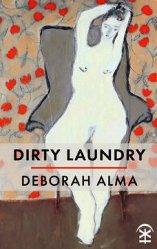

Dirty Laundry

Deborah Alma

Nine Arches Press

ISBN 9-781911-027416

76 pages, £9.99

Dirty Laundry

Deborah Alma

Nine Arches Press

ISBN 9-781911-027416

76 pages, £9.99

There’s a demolition firm based in my home town of Nottingham called Total Reclaims. It’s a name that suggests not just a tearing down, but a taking back. Dirty Laundry does a total reclaims job on a number of things – not least male attitudes, behaviours and perceptions – but uses, instead of wrecking balls and bulldozers, wry humour, earthy experience, incisive language and admirable concision. This is the full text of ‘Playing Scrabble with my new lover’, a piece that comes toward the end of the book:

So stupid, but I hadn’t remembered

that the last time I’d played

was in the old house,

until I found the four stubby pencils

and old scores, settled.

I poured the wine, apologised

for not being much fun,

while he spelt out LOVE;

But his score was only seven

and I said,

You should have kept the V

for another time.

“So stupid”, a rueful self-j’accuse, demands attention from the outset. Small details follow – “the old house”, “four stubby pencils” – that bring the reader up to speed with the narrator’s life, as if she were an acquaintance we’d not seen in a while but know well enough that these throwaway references are all the information we need. Line five fizzes, the double meaning of “old scores, settled” landing with real weight. The second stanza, in just fifteen words, pulls off a taut comparison between the narrator and the ‘new lover’: she’s pragmatic, self-aware; he’s gauche, awkward, trying too hard. Stanza three delivers a bluntly effective pay-off, Alma making two reclaims from male vernacular. Look at “score” – in laddish colloquy, a reference to a sexual conquest – and how Alma follows it with “only” and consolidates it, two lines later, with “another time”. It’s clear that the wannabe Lothario isn’t going to score – not in this poem, anyway. Then look at “V”, a single letter positively loaded with toxic masculinity, from Churchillian V for Victory swagger to its use as a truncation of ‘versus’: a letter redolent of taking sides, squaring off against an antagonist, fighting. Not to mention its calling to mind of Tony Harrison’s book-length poem, itself a pressure cooker of political protest, unionism and the class war.

All told, the letter V is freighted with blokeishness, just as many uses of the word “score” (a debt to be settled aggressively, the acquisition of drugs, going one up against opposing team) are blokey. To witness Alma reclaiming them with such verve is delicious. In ‘Borderline’, the poet is questioned by three male voices – those of a therapist, a terrapin and a terrorist – and emphatically rejects each of them. The terrapin is a surreal but inspired inclusion. Here’s their dialogue:

Do you eat the shells of eggs asked the terrapin?

No! I munch through them,

using red claws and truths,

spitting out the grit from the blood

but when I get to the heart,

though it cannot be broken and is not mine,

I am gentle and leave it alone.

Good! he said.

There’s a lot going on here, but Alma’s rephrasing of Tennyson’s famous line from ‘In Memoriam A.H.H.’ leaps out immediately. The familiarity of “red in tooth and claw” is what Alma banks on to make the homophonic substitution of “truths” for “tooth” work so well. Her reclaiming of Stephen Crane’s ‘In the Desert’ (“It is bitter – bitter … // “But I like it / “Because it is bitter / “And because it is my heart”) is subtler, sneakier and achieved with panache.

Again without explicitly referencing the earlier work, the portrayal in ‘Lift Him Up Out’ of an unemotionally immature man yearning for the kind of fantasy woman who

would lift him up out

of the wreckage of the car crash by his cock

and his pinched nipples, his body arched up

and greedy for her mouth …

struck me as a reclaiming of James Dickey’s technically impressive but quasi-pornographic ‘Falling’ (the one about the air hostess denuded by the slipstream as she falls to her death), but whereas Dickey’s fantasia sprawls out across five pages, Alma’s slap down occupies all of ten lines.

It would be remiss of me, though, to suggest that these reclaimings are the aesthetic raison d’être of the collection. For all that Alma conjures connections (and correctives) to other work, the chief pleasure of Dirty Laundry is to experience the arrival of a feisty, intelligent and defiant voice that is entirely the poet’s own. A voice, moreover, that is unafraid to tackle thorny subjects, sometimes satirically (the sexual hypocrisy of the Catholic Church is rendered as a walk-through of preserved pontifical penises in ‘The Head of the Church in Rome’), sometimes with unflinching directness (‘Chicken’, one of the shortest pieces in the book, is a stark distillation of abusive relationships), and sometimes with such gossamer-light sensitivity that the reader realises that to have taken any other approach would have seen the poem implode under its own weight.

As an example of the latter: Dirty Laundry’s opening poem, ‘Flock’. Dedicated to the memory of Jo Cox, it purposefully avoids any mention of the circumstances of her death or the right-wing radicalisation of her murderer. Alma writes of chickens dying on a farm, the “unexpected heat”, the “hollyhocks and hedge-clippings”, and amidst this agglomeration of detail the observation that

In the news, a woman died

and for days the rain,

so that the roses rotted in the bud …

The red of the rose evoking the red rosette Cox wore as a Labour MP is Alma’s only political reference; the thrust of the poem is its quietness, its communication of loss by means of a via negativa. Leading off the collection with it was a gambit: in many ways, it’s not indicative of Dirty Laundry’s bolshy, ballsy commitment to exist on its own terms. ‘Flock’ is quiet, mournful, suffused with regret. But that’s why the gambit pays off: once the needless death of a woman whose commitment to social betterment has been recorded and reflected on, Dirty Laundry rolls up its sleeves and gets on with the business at hand: taking back language, narrative, scenarios and experiences from the kind of patriarchal blowhards who would doubtless yawp and bluster and cry foul to see themselves reflected in these pages.

Nov 26 2018

London Grip Poetry Review – Deborah Alma

Neil Fulwood compliments Deborah Alma for a collection which rolls up its sleeves and gets down to business

There’s a demolition firm based in my home town of Nottingham called Total Reclaims. It’s a name that suggests not just a tearing down, but a taking back. Dirty Laundry does a total reclaims job on a number of things – not least male attitudes, behaviours and perceptions – but uses, instead of wrecking balls and bulldozers, wry humour, earthy experience, incisive language and admirable concision. This is the full text of ‘Playing Scrabble with my new lover’, a piece that comes toward the end of the book:

“So stupid”, a rueful self-j’accuse, demands attention from the outset. Small details follow – “the old house”, “four stubby pencils” – that bring the reader up to speed with the narrator’s life, as if she were an acquaintance we’d not seen in a while but know well enough that these throwaway references are all the information we need. Line five fizzes, the double meaning of “old scores, settled” landing with real weight. The second stanza, in just fifteen words, pulls off a taut comparison between the narrator and the ‘new lover’: she’s pragmatic, self-aware; he’s gauche, awkward, trying too hard. Stanza three delivers a bluntly effective pay-off, Alma making two reclaims from male vernacular. Look at “score” – in laddish colloquy, a reference to a sexual conquest – and how Alma follows it with “only” and consolidates it, two lines later, with “another time”. It’s clear that the wannabe Lothario isn’t going to score – not in this poem, anyway. Then look at “V”, a single letter positively loaded with toxic masculinity, from Churchillian V for Victory swagger to its use as a truncation of ‘versus’: a letter redolent of taking sides, squaring off against an antagonist, fighting. Not to mention its calling to mind of Tony Harrison’s book-length poem, itself a pressure cooker of political protest, unionism and the class war.

All told, the letter V is freighted with blokeishness, just as many uses of the word “score” (a debt to be settled aggressively, the acquisition of drugs, going one up against opposing team) are blokey. To witness Alma reclaiming them with such verve is delicious. In ‘Borderline’, the poet is questioned by three male voices – those of a therapist, a terrapin and a terrorist – and emphatically rejects each of them. The terrapin is a surreal but inspired inclusion. Here’s their dialogue:

There’s a lot going on here, but Alma’s rephrasing of Tennyson’s famous line from ‘In Memoriam A.H.H.’ leaps out immediately. The familiarity of “red in tooth and claw” is what Alma banks on to make the homophonic substitution of “truths” for “tooth” work so well. Her reclaiming of Stephen Crane’s ‘In the Desert’ (“It is bitter – bitter … // “But I like it / “Because it is bitter / “And because it is my heart”) is subtler, sneakier and achieved with panache.

Again without explicitly referencing the earlier work, the portrayal in ‘Lift Him Up Out’ of an unemotionally immature man yearning for the kind of fantasy woman who

struck me as a reclaiming of James Dickey’s technically impressive but quasi-pornographic ‘Falling’ (the one about the air hostess denuded by the slipstream as she falls to her death), but whereas Dickey’s fantasia sprawls out across five pages, Alma’s slap down occupies all of ten lines.

It would be remiss of me, though, to suggest that these reclaimings are the aesthetic raison d’être of the collection. For all that Alma conjures connections (and correctives) to other work, the chief pleasure of Dirty Laundry is to experience the arrival of a feisty, intelligent and defiant voice that is entirely the poet’s own. A voice, moreover, that is unafraid to tackle thorny subjects, sometimes satirically (the sexual hypocrisy of the Catholic Church is rendered as a walk-through of preserved pontifical penises in ‘The Head of the Church in Rome’), sometimes with unflinching directness (‘Chicken’, one of the shortest pieces in the book, is a stark distillation of abusive relationships), and sometimes with such gossamer-light sensitivity that the reader realises that to have taken any other approach would have seen the poem implode under its own weight.

As an example of the latter: Dirty Laundry’s opening poem, ‘Flock’. Dedicated to the memory of Jo Cox, it purposefully avoids any mention of the circumstances of her death or the right-wing radicalisation of her murderer. Alma writes of chickens dying on a farm, the “unexpected heat”, the “hollyhocks and hedge-clippings”, and amidst this agglomeration of detail the observation that

The red of the rose evoking the red rosette Cox wore as a Labour MP is Alma’s only political reference; the thrust of the poem is its quietness, its communication of loss by means of a via negativa. Leading off the collection with it was a gambit: in many ways, it’s not indicative of Dirty Laundry’s bolshy, ballsy commitment to exist on its own terms. ‘Flock’ is quiet, mournful, suffused with regret. But that’s why the gambit pays off: once the needless death of a woman whose commitment to social betterment has been recorded and reflected on, Dirty Laundry rolls up its sleeves and gets on with the business at hand: taking back language, narrative, scenarios and experiences from the kind of patriarchal blowhards who would doubtless yawp and bluster and cry foul to see themselves reflected in these pages.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2018 0 • Tags: books, Neil Fulwood, poetry