John Forth welcomes Robert Walton’s second collection – even if it comes a long time after the first

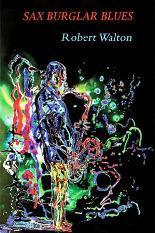

Sax Burglar Blues

Robert Walton

Seren Books (2017)

ISBN 9 7871781 724088

64pp £9.99

Sax Burglar Blues

Robert Walton

Seren Books (2017)

ISBN 9 7871781 724088

64pp £9.99

You have to love the Anglo-Welsh parallel world of Waltonia, with its insect-man carrying a double bass through crowded streets, its mournful victim of saxophone theft, its myths made into family and its family myths, an armed man insisting he pay more for a book – and Geoff, who dreams of owning a Maserati. All of these people are brought to life in persuasive detail, but Walton can also take risks with conceits – one, a meditation on ‘Greenland’, begins with five unusual couplets on a view from the air and ends:

It's a head on the shoulders of the globe, the ocean

swirling round it, a gown that should lend it grace.

It's a head at rest on a pillow and I'm willing my mother's

eyes to open. I'm looking for a flicker of green.

[‘Greenland’]

A comic outcome of such trickery can be found in ‘A Bus Named Dusty’ – complete with remembered mannerisms and songs which conspire to make it more than, but finally only, a bus. There follow a number of poems that recall the young musician, Walton, dreaming of a cruelly thwarted career. In ‘Sax Burglar Blues’ the speaker unashamedly romanticises his stolen sax:

As he crept through the darkness to ease

you from the stand where you sat

like a swan in the reeds – could he hear

your stabs and riffs, fierce

and rhythmic as wings beating the waters,

rising into the groove of the air?

In ‘Three Out of Four Original Members’ the one who gave up the business, or was left behind, recalls with bitterness and great good humour the life lost:

To look at me then and now you'd never think

I cut that twelve-bar riff in a single take.

Many of the poems tread the fine line between sentiment and cynicism without falling off – and the results are often funny – such as when four very different points of view are taken of, and by, a canary named Joey. His speech in the final poem, ‘Joey for President’, is a million miles from a roosting hawk yet strangely prescient:

Mr President, sir, they say –

checking the windows are sealed –

come out and see the world.

Cut a deal on millet

harvests. Raid the supplies

of canary grass. Splatter

your droppings far and wide.

There’s a swashbuckling tribute to the Welsh poet, John Tripp, and an entirely different memorial to Seamus Heaney which presents an imagined encounter between the poet and a boy trying to write answers about him in an exam, observed by an uncomfortable schoolmaster:

(He'd) given up on his five hundred words analysis

of imagery in Digging and The Early Purges to busy

himself instead with drawing a pair of devil's horns

and lascivious goatee-beard on your photograph...

[‘Invigilation’]

In what is clearly an affectionate address to Heaney, the final effect is typical of many of Walton’s poems in which the reader is left slightly wrong-footed, suspended almost, between the bizarre and the genuine. Something similar occurs in ‘Knocking Up a Garden Planter’ which offers a detailed account of the lengths to which a non-carpenter will go in order to ensure his flawed masterpiece will stand up when filled with earth. If the woodwork is bodged, the comedy is not, and that is the real strength of the poem, though for me it’s almost spoiled by a dreamlike happy ending.

The genesis of all this is presumably to be found in a couple of terrific classroom poems featuring Mrs.Jones, who might have given the young Walton his early love of verse – one in particular where the class performs a piece about Twm the highwayman and which ends with the lines:

Those winter

afternoons, when she stood at the front of the room,

wiry-haired, fierce-eyed, her words

were red kites playing the thermals over the Teifi.

[‘Twm Sion Cati’]

There is a handful of poems to Grandparents – tributes full of understated family warmth – and a sad recollection of his Dad’s passion for Cardiff City which the young Bob never quite shared or even understood. Some of the same devotion is diverted towards natural scenes and causes, and

‘Observation Post’ reports on an otter-watch scheme with rapt attention:

Our night-vision technology monitors the advance

of sleek snouts, eyes, ears rippling the surface.

We lose them when they arch their backs and dive.

The book spans most of a life, since Walton’s first poems appeared in the 1970s and this is his second collection, suggesting that Seren have bagged a cut-price ‘Selected’. Written by the early, middle and later Walton selves, it is lively and invigorating stuff.

Dec 13 2017

John Forth welcomes Robert Walton’s second collection – even if it comes a long time after the first

You have to love the Anglo-Welsh parallel world of Waltonia, with its insect-man carrying a double bass through crowded streets, its mournful victim of saxophone theft, its myths made into family and its family myths, an armed man insisting he pay more for a book – and Geoff, who dreams of owning a Maserati. All of these people are brought to life in persuasive detail, but Walton can also take risks with conceits – one, a meditation on ‘Greenland’, begins with five unusual couplets on a view from the air and ends:

It's a head on the shoulders of the globe, the ocean swirling round it, a gown that should lend it grace. It's a head at rest on a pillow and I'm willing my mother's eyes to open. I'm looking for a flicker of green. [‘Greenland’]A comic outcome of such trickery can be found in ‘A Bus Named Dusty’ – complete with remembered mannerisms and songs which conspire to make it more than, but finally only, a bus. There follow a number of poems that recall the young musician, Walton, dreaming of a cruelly thwarted career. In ‘Sax Burglar Blues’ the speaker unashamedly romanticises his stolen sax:

In ‘Three Out of Four Original Members’ the one who gave up the business, or was left behind, recalls with bitterness and great good humour the life lost:

Many of the poems tread the fine line between sentiment and cynicism without falling off – and the results are often funny – such as when four very different points of view are taken of, and by, a canary named Joey. His speech in the final poem, ‘Joey for President’, is a million miles from a roosting hawk yet strangely prescient:

There’s a swashbuckling tribute to the Welsh poet, John Tripp, and an entirely different memorial to Seamus Heaney which presents an imagined encounter between the poet and a boy trying to write answers about him in an exam, observed by an uncomfortable schoolmaster:

(He'd) given up on his five hundred words analysis of imagery in Digging and The Early Purges to busy himself instead with drawing a pair of devil's horns and lascivious goatee-beard on your photograph... [‘Invigilation’]In what is clearly an affectionate address to Heaney, the final effect is typical of many of Walton’s poems in which the reader is left slightly wrong-footed, suspended almost, between the bizarre and the genuine. Something similar occurs in ‘Knocking Up a Garden Planter’ which offers a detailed account of the lengths to which a non-carpenter will go in order to ensure his flawed masterpiece will stand up when filled with earth. If the woodwork is bodged, the comedy is not, and that is the real strength of the poem, though for me it’s almost spoiled by a dreamlike happy ending.

The genesis of all this is presumably to be found in a couple of terrific classroom poems featuring Mrs.Jones, who might have given the young Walton his early love of verse – one in particular where the class performs a piece about Twm the highwayman and which ends with the lines:

Those winter afternoons, when she stood at the front of the room, wiry-haired, fierce-eyed, her words were red kites playing the thermals over the Teifi. [‘Twm Sion Cati’]There is a handful of poems to Grandparents – tributes full of understated family warmth – and a sad recollection of his Dad’s passion for Cardiff City which the young Bob never quite shared or even understood. Some of the same devotion is diverted towards natural scenes and causes, and

‘Observation Post’ reports on an otter-watch scheme with rapt attention:

The book spans most of a life, since Walton’s first poems appeared in the 1970s and this is his second collection, suggesting that Seren have bagged a cut-price ‘Selected’. Written by the early, middle and later Walton selves, it is lively and invigorating stuff.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, John Forth, poetry