Pamela Johnson takes an in-depth look at a significant selection of poetry from Martina Evans

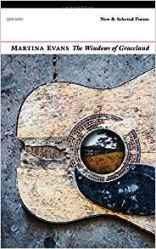

The Windows of Graceland: New & Selected Poems Martina Evans Carcanet ISBN 978-1784102760 136pp £12.99

The Windows of Graceland brings together generous selections from Evans’s four previous collections, plus nine new poems. First and foremost it’s a good read. As characters and settings recur, the effect is not unlike settling into a collection of short stories. This is not surprising since Evans has published almost as much fiction as poetry. In the title poem of her third collection, Facing The Public, these lines sound the keynote of her poetics:

And yet, she could chalk up a picture in a handful of words conjure a person in a mouthful of speech; she took off her customers to a captivating T, captivating us all in the kitchen, drawing a bigger audience than she bargained for.

Here, the speaker’s mother is caught impersonating a customer when the man himself is standing quietly at the back of the shop. If this is Evans’s mother then she has her mother’s gifts, transferred from shop counter to page and stage.

At live readings Martina Evans gives a compelling performance. Like her mother, she can hold the floor. She manages, too, to render a performance-on-the-page with her storyteller’s talent for scoring a character’s voice in such a way that we ‘hear’ it as we read. The mother again:

. She never grumbled, because No one likes a grumbler, . I never grumble but the pain I have in my two knees this night . there isn’t a person alive who wouldn’t stand for it.

The mother’s voice is threaded through all the collections, as is Burnfort, County Cork, the place of Evans’s childhood. She returns to the town and to the family business – shop, petrol pumps, pub – to evoke vivid events both personal and political.

The poetry of speech patterns and idioms is also used effectively to call up darker moments of Irish history. In ‘The Boy From Durras,’ everyday phrases resonate, revealing how a troubled past, the Black & Tans looking for information in a small community, is not forgotten (even after seventy years) but neither is it spoken of. The reader is drawn into a confidence, ‘I’ll tell you something now on the quiet.’ Throughout the poem, a refrain, ‘you’ll get no one round here to talk about it.’ It ends with, ‘And don’t forget that you never heard this from me.’

While Evans wouldn’t deny her drawing upon autobiography, there isn’t the sense of a life transcribed; rather she dramatises key moments of family relationships and cultural/political events. She has spoken elsewhere of fictional elements in her poems; the speaker might not always be the poet. Her talent is to blend the cadence of a voice, with flights of fancy to reach for an emotional truth. This frees the poems from any sense of the relentless confessional of, say, Sharon Olds. Instead, there is playfulness with serious intent. Evans is a poet who looks out at the world and sees it from many angles.

Her first collection, published in 1998, All Alcoholics Are Charmers, largely explores a childhood in Ireland. She gets right inside the child’s point of view, as in ‘The Black Priest:’

It was hard to pretend our normal indifference with his big legs doubled up in the nun’s chair. Someone next to me whispered that his knees were like rockets.

The nun is, ‘an arrangement/of dark folds of cloth/in the corner, quivering.’

Here, Evans works with a short line and verse breaks. Over the collections, and in particular with the monologues or re-tellings of history, she works with a fine-tuned lineation in a block of text, where cadence and handling of syntax produces the poem.

Over the twenty years of her publishing the storytelling is a constant; but later work sees bolder explorations of Irish history and also, on a lighter note, her contemporary life in Dalston, London, herself now a mother.

We get a first glimpse of that area of London in her second collection, Can Dentists Be Trusted? in the poem, ‘On Living in An Area of Manifest Greyness and Misery’ – it has to be said, Evans has an eye for a good title – this being a quote from Peter Ackroyd’s book on London. She plays with Ackroyd’s notion of London as ‘a vast ocean in which survival is not certain.’ There is a sense of the poet shipwrecked.

. I sleep high on the bird’s nest. . Trucks and lorries shake the house . and make the bricks tremble, . roaring tidal waves rock the bed

Based on the selection presented here, the second collection seems to be the weakest, but there is ambition in the long poem, ‘The Rabach.’ In order fully to appreciate this narrative I had to Google the story of 19thC murderer of the title. On a second read, it was then easier to appreciate the compression of her storytelling, which perhaps needed a longer line or even a ballad form. What remains vivid in the poem is the stark beauty of the remote glen, ‘two hours walk/from the road,’ set against the terror of the murders.

The Rabach hid the body under the hearth stone, leaned out in the early morning, to smoke a pipe. Gatekeepers and painted ladies skimmed the bog, grasshoppers gritted among the purple loosestrife spotted orchids and fever few.

It’s in her next collection, Facing The Public, where poems that retell significant moments of Irish history are done with great confidence. ‘Mallow Burns, 28th September, 1920’ is a tour de force. In a single sentence, that travels over 36 long lines, Evans dramatises an event in which the IRA storm an English barracks in Co. Cork to raid it for weapons. They choose a moment when all the soldiers, bar one guard, are out riding. In reprisal the town of Mallow is burned down, women raped, businesses wrecked. Masterful, here, is the handling of point of view. Evans begins in the viewpoint of the one guard, who is killed as he resists the raid, focussing on what he can hear. Turning to the consequences of the raid, barely pausing for breath, she pivots away from the dead guard with ‘and he won’t hear …’ as she powers through:

… screams, the creamery on fire, three hundred jobs gone, Town Hall flaming, houses alight, holy pictures bayoneted and one pregnant woman hiding beside the stones in the graveyard is too cold by the time the sun rises to ever get up again.

Impressive is the control of indignation at the perceived injustice, there’s a kind of exhilaration in being able to summon it up vividly in a controlled flow of words.

There is a generous heart in wanting to retell such stories, and often a consideration of other viewpoints, as in the title poem of her fourth collection, Burnfort, Las Vagas.

As the men come down from the mountain and fill their vans with petrol – a violet cloud with a tantalizing smell and someone says Burnfort is like New York to those mountainy men the way it is all built up with a school and a church and a post office and us city slickers running the pub, shop and petrol pumps … only now I think it was more like Vegas, all those signs, the games of forty-five and my Elvis tape playing

Elvis – his singing and his dying – features frequently, which perhaps accounts for the title of the book, but Burnfort itself might be seen as a place of grace.

Of the London poems, ‘I want to be like Frank O’Hara’ is another tour de force, a playful homage to the man and his lunch poems.

but I’ve never leaned unhurriedly on a club doorway listening to Billie Holiday. Most of my time in this city I’ve been a mother and I know I’ve spent too much time in Sainsbury’s Dalston branch even if it does have its own inimitable vibe and a huge range of root vegetables.

Throughout, we sense Evans is a voracious reader, a real bookworm. It’s there in the intertextuality of the Frank O’Hara poem and in her frequent use of an epigraph, as if writing a poem is an extension of her reading. There are several poems which celebrate the powerful effects of reading, such as, ‘The Mobile Library’ in her first collection and ‘The Green Storybook,’ which ends this volume.

If I have one quibble, it’s that, occasionally, she loses the music. The writing is always strong, it never disappoints, as she creates the texture of life and conjures up characters in a few words, such as ‘… Mrs Callaghan’s/boyfriend who wore a cowboy hat/and cradled a big brandy on his beige thigh…’ However good the writing is it always poetry? That may seem like hair-splitting but, for example the first of the new poems, ‘Fine Gael Form a Coalition Government with Labour, March 1973,’ I couldn’t quite see why this was lineated. It’s a fascinating piece of writing but I’d have happily read this as a piece of prose.

There’s quietness with other poems among the new, the best of which – ‘Watch’, ‘Everything Including This Room Is a Future Ruin’ and ‘The Irish Airman Parachutes to Earth’ – are meditations on time.

Unlike the mortified mother in Facing The Public, Evans faces her subjects and her public, looks them in the eye, speaks boldly and enticingly. This generous book is one to savour and re-read.

.

Pamela Johnson is a novelist & poet. Her third novel, Taking In Water, (Blue Door Press, 2016, https://bluedoorpress.co.uk/) was supported by an Arts Council Writers’ Award. Her poems appear in anthologies. She teaches fiction on the MA in Creative & Life Writing, Goldsmiths. Her blog, Words Unlimited, publishes interviews with writers, including poets http://wordsunlimited.typepad.com/words_unlimited/

13/06/2017 @ 08:45

Thanks for an excellent and perceptive review… and thank you London Grip. But, I did get a shiver reading it. Fake news might be sexier than the disappearing muddle called truth but do we have to accept it? Especially now. Ok, a bit over the top, we’re not exactly talking news here, and most poets are creative with their history. Anyway, my favourite Martina Evans collection is her first, The Inniscarra Bar and Cycle Rest, not mentioned in her Selected. It’s there on the web on the Carcanet author page.