Roderick Burns is taken aback by the diversity of a short story collection from Nigel Jarrett

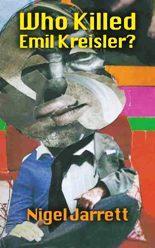

Who Killed Emil Kreisler?

Who Killed Emil Kreisler?

Nigel Jarrett

Cultured Llama Publishing

ISBN: 9-780956-892119

Price: £12.00

Who Killed Emil Kreisler? is a book of contradictions: twenty stories that range widely across the globe and time, but find their best expression in the small moments of unremarkable British lives; individual pieces that set up grand themes over many pages, but peter out and ultimately disappoint, and others tucked away quietly that accomplish everything it is possible to do in a story, effortlessly, in a couple of pages; moments of exquisite subtlety that occur in otherwise unmemorable passages of prose. It is not that any of the book isn’t well-written, line by line or page by page, nor is it simply uneven. Emil Kreisler seems to delight in undermining its own momentum, in presenting the reader with pockets of brilliance and stodginess packed together like the rich and poor quarters of a mysterious city. It is at once a fascinating and frustrating experience.

Take the variety of the stories. Within the first half dozen or so, we move from a Swedish zoo to a remote school in war-torn Republic of Congo, to Berlin, Los Angeles, New England and London; and from a curdled love story to a meditation on the stickiness of family, a stylised cold war squib, a somewhat flat story of cultural integration and a delightful object-biography tracing the fall of a ceremonial helmet. This pattern continues throughout the book – the pieces are almost wilfully diverse, taking in a raft of countries and cultures, capitals, landscapes and cityscapes, and a gallery of occupations, from dressers to fading movie stars to circus performers, obscure musicians, architectural salvage experts and collectors of rare Japanese erotic prints. In a volume of less than 200 pages, this degree of variety is a little bewildering.

It comes as a relief, therefore, when a story such as ‘Wish You were Here’ anchors itself in the bland reality of contemporary Britain, calming things down and offering a superb, compact tale of mystery with a dash of homegrown Paul Auster and a lovely, lingering feel for character and situation. Moving on in place and time from his Jewish neighbour Helsa, the narrator receives a series of odd, antiquated postcards from around the country. They are unexplained, continue over the years after her death, and ultimately seem inexplicable (possibly being sent by her waspish brother) but serve to highlight the transient nature of relationships and our grip on the world. There is nothing flashy or clever about the postcard device. It is not a conceit, but nor is it thrown in simply for flavour or without purpose. Along with the plangent title, it brings out the solid achievement of the story perfectly:

. “The latest picture … was of Land’s End, but before it became a busy tourist attraction. The photographer must

. have stationed himself on the rocks in front of the lighthouse and waited for one of the place’s memorable

. sunsets. Helios obliged. But, like the others, it was a turn-of-century sepia print, lightly-coloured, the card

. slightly rubbed at the edges – and again the wavy, spectral start of a written message, abandoned before it had

. got under way.”

This seems to me a superb image, in both detail and implication, for the human condition, embedded in a six-page story unfolding in the background. By contrast, the marquee stories – ‘Rhapsodie’ (32 pages), ‘A Weissman Girl’ (12) – occupy great chunks of the book, and are in themselves well-developed, but build over many pages to disappointing ends, petering out or claiming bold, universal conclusions (“the family, that ‘dear octopus’ from whose tentacles we never quite escape”) that they have failed to earn.

The frustration for the reader comes from breezing through the more compact stories, feeling their quality, and coming across passages of great virtuosity and inventiveness:

. “Sometimes, when I was sitting with him, my attention would wander and I would compare his atrophied state

. to a soluble aspirin fizzing to nothing in a glass of water” (‘Beauty’)

. “It was a typical Tuesday afternoon in the Doyle household above Bridget’s maisonette. Or would have been if

. thoughts of sundry lasses with flat chests and names like Monaghan and Doherty had not been making the old

. boy’s eggshell eyes dance like a pair of sunlit Kerry elves” (‘My Galway Rose’)

. “A Polaroid picture arrived one day in a envelope, It showed Emmanuel and his ‘Front’ colleagues with rifles

. and other weapons that seemed too heavy for them to lift. Each was garlanded with leather loops of bullets”

. (‘The Brazzaville Express’).

However, cheek by jowl with these vivid pieces will be a story (‘Mandalay’ comes to mind, or ‘Miss Mercedes Gleitze’) which takes great trouble to establish characters in diverse settings who don’t do very much at all: a Caribbean immigrant partially integrating into British society in the first, a loose circle of friends inadvertently causing the dismissal of a maid from her job serving the Welsh mine-owning elite in the second.

Perhaps, borrowing the notion of a variegated city, the reader should not expect to wander through neighbourhoods consistent with each other in tone and character; the author may intend the book to be experienced as the random hodgepodge of London or New York, with a great deal of variety but little predictability. But sorry to say, for this reader, the frustration outweighs the fascination, in the end.

Roderick Burns is taken aback by the diversity of a short story collection from Nigel Jarrett

Nigel Jarrett

Cultured Llama Publishing

ISBN: 9-780956-892119

Price: £12.00

Who Killed Emil Kreisler? is a book of contradictions: twenty stories that range widely across the globe and time, but find their best expression in the small moments of unremarkable British lives; individual pieces that set up grand themes over many pages, but peter out and ultimately disappoint, and others tucked away quietly that accomplish everything it is possible to do in a story, effortlessly, in a couple of pages; moments of exquisite subtlety that occur in otherwise unmemorable passages of prose. It is not that any of the book isn’t well-written, line by line or page by page, nor is it simply uneven. Emil Kreisler seems to delight in undermining its own momentum, in presenting the reader with pockets of brilliance and stodginess packed together like the rich and poor quarters of a mysterious city. It is at once a fascinating and frustrating experience.

Take the variety of the stories. Within the first half dozen or so, we move from a Swedish zoo to a remote school in war-torn Republic of Congo, to Berlin, Los Angeles, New England and London; and from a curdled love story to a meditation on the stickiness of family, a stylised cold war squib, a somewhat flat story of cultural integration and a delightful object-biography tracing the fall of a ceremonial helmet. This pattern continues throughout the book – the pieces are almost wilfully diverse, taking in a raft of countries and cultures, capitals, landscapes and cityscapes, and a gallery of occupations, from dressers to fading movie stars to circus performers, obscure musicians, architectural salvage experts and collectors of rare Japanese erotic prints. In a volume of less than 200 pages, this degree of variety is a little bewildering.

It comes as a relief, therefore, when a story such as ‘Wish You were Here’ anchors itself in the bland reality of contemporary Britain, calming things down and offering a superb, compact tale of mystery with a dash of homegrown Paul Auster and a lovely, lingering feel for character and situation. Moving on in place and time from his Jewish neighbour Helsa, the narrator receives a series of odd, antiquated postcards from around the country. They are unexplained, continue over the years after her death, and ultimately seem inexplicable (possibly being sent by her waspish brother) but serve to highlight the transient nature of relationships and our grip on the world. There is nothing flashy or clever about the postcard device. It is not a conceit, but nor is it thrown in simply for flavour or without purpose. Along with the plangent title, it brings out the solid achievement of the story perfectly:

. “The latest picture … was of Land’s End, but before it became a busy tourist attraction. The photographer must

. have stationed himself on the rocks in front of the lighthouse and waited for one of the place’s memorable

. sunsets. Helios obliged. But, like the others, it was a turn-of-century sepia print, lightly-coloured, the card

. slightly rubbed at the edges – and again the wavy, spectral start of a written message, abandoned before it had

. got under way.”

This seems to me a superb image, in both detail and implication, for the human condition, embedded in a six-page story unfolding in the background. By contrast, the marquee stories – ‘Rhapsodie’ (32 pages), ‘A Weissman Girl’ (12) – occupy great chunks of the book, and are in themselves well-developed, but build over many pages to disappointing ends, petering out or claiming bold, universal conclusions (“the family, that ‘dear octopus’ from whose tentacles we never quite escape”) that they have failed to earn.

The frustration for the reader comes from breezing through the more compact stories, feeling their quality, and coming across passages of great virtuosity and inventiveness:

. “Sometimes, when I was sitting with him, my attention would wander and I would compare his atrophied state

. to a soluble aspirin fizzing to nothing in a glass of water” (‘Beauty’)

. “It was a typical Tuesday afternoon in the Doyle household above Bridget’s maisonette. Or would have been if

. thoughts of sundry lasses with flat chests and names like Monaghan and Doherty had not been making the old

. boy’s eggshell eyes dance like a pair of sunlit Kerry elves” (‘My Galway Rose’)

. “A Polaroid picture arrived one day in a envelope, It showed Emmanuel and his ‘Front’ colleagues with rifles

. and other weapons that seemed too heavy for them to lift. Each was garlanded with leather loops of bullets”

. (‘The Brazzaville Express’).

However, cheek by jowl with these vivid pieces will be a story (‘Mandalay’ comes to mind, or ‘Miss Mercedes Gleitze’) which takes great trouble to establish characters in diverse settings who don’t do very much at all: a Caribbean immigrant partially integrating into British society in the first, a loose circle of friends inadvertently causing the dismissal of a maid from her job serving the Welsh mine-owning elite in the second.

Perhaps, borrowing the notion of a variegated city, the reader should not expect to wander through neighbourhoods consistent with each other in tone and character; the author may intend the book to be experienced as the random hodgepodge of London or New York, with a great deal of variety but little predictability. But sorry to say, for this reader, the frustration outweighs the fascination, in the end.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, Roderick Burns