Reading Gail White’s collection makes D A Prince think again about some conventional assessments of ‘light’ verse

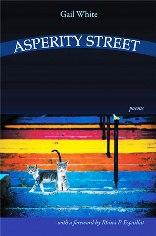

Asperity Street

Gail White

Able Muse Press

ISBN 978-1-927409-54-1

98 pp $18,95

Asperity Street

Gail White

Able Muse Press

ISBN 978-1-927409-54-1

98 pp $18,95

Wit in poetry is a serious business and a collection of poems using wit in a multitude of forms is even more so. Formal poetry is unforgiving and each slip is magnified by the reader’s expectation; any slip becomes an enormity, towering above those poems whose seemingly effortless lines have slotted together in perfection. Is that why relatively few poets choose to work within the challenges of metre and rhyme? A pitch-perfect ear for the natural tilt and fall of quotidian speech patterns isn’t given to everyone. It isn’t for poets who choose a solitary garret or a lofty mountain top; it’s for those who gossip, eavesdrop, mix at all levels in their communities – poets who get out and about, alert to the everlasting oddities and entertainments of the world. To call it ‘light’ verse doesn’t, quite, capture the blend of skills required to create a short, pithy, perfectly-formed snapshot of human experience, though ‘lightness’ is part of the skill – an ability to float unexpected ideas in accessible forms. Gail White takes her ‘light’ verse seriously but wears her achievements lightly, without pretension. This is a cracker of a collection.

Growing; Working; Holding; Leaving. These headings divide the collection into four near-equal parts and guide the reader. This is ‘life’, roughly – as the opening lines indicate.

Childhood is wretched, even if you’re not

abused and have no scars to show in court.

Children are powerless and moneyless

and worst of all, they’re short.

So childhood is ‘The Prison’ (the title of this poem) – a reassuringly realistic reminder of what it was like when grown-ups (‘taller gods’) carried on their lofty discussions above our heads. White (and I) belong to that time when children were small, unconsulted, unheard; we were loved but in a somewhat undemonstrative way. We took it for granted that this was what life was like. It’s refreshing to find this openly acknowledged and the dodgy notion of childhood idyll confronted. But the poem’s final line offers our escape route – ‘At any price, grow tall.’ A single sentence, with a spring into the life-after-childhood world. White is good at final lines a a crisp face-up-to-it ending that throws the poem back into the reader’s space.

Let’s look at some of these endings, for their own sake:

If only you had fur and she had brains. (‘She Compares Her Lover to Her Cat’)

I’ve come to love these strangers now they’re dead. (‘Old Photographs’)

And now my death begins its work. (‘Diagnosis Day’)

Some stories look so strange they might be true. (‘Nativity Scene’)

They are not joke-y, not flip. Clever endings: they don’t close the lid on the poem but linger – and, because White has an ear for the rhythm lying between poems, lead into the next poem. So, for example, the end of ‘Old Photographs’ (above) is followed by ‘Haunted’, the final poem in the Growing section.

My mother was burned, not buried,

as if we were afraid that she

would rise up out of a concrete vault

and trouble her family.

One poems tempers another; we (her readers) are given space to make the connection between the love that ends the previous poem and a mother whose presence could be troublesome. ‘A Rolling Stone Gathers Wisdom’, as the opening poem of Working tells us, in a perfect Housman pastiche –

When I was five-and-thirty

I thought that I was old,

my waist no longer sylph-like

my hair no longer gold.

’Twas useless to console me

or offer me champagne,

for I was five-and-thirty

and death was on my brain.

Housman looks so easy to pastiche but he’s not: the flow of ideas has to be uninterrupted, unforced – as it is here. But where is the wisdom? – in the final lines:

But there’ve been subtle changes

in Nature’s paradigm –

now I am five-and-sixty

and I’ve got lots of time.

In her excellent introduction to this collection, Rhina S. Espaillat calls the final line an ‘almost-placid comment’; it’s the one point on which I disagree with her. For me this is darkly ironic; I can hear a ghostly echo of the pantomime Oh no you haven’t from the reader’s side. It’s two-edged. On one side ‘wisdom’ means not dwelling on death all the time; on the other, we all know we don’t have lots of time. The collection will return to this later, but for now there’s ‘Work’ –

It’s only artists and the very rich

who work for the sheer love of what they do.

Most jobs are rounds of routine boredom which

set up the hoops we all keep jumping through

just for the food and drink that makes us strong

enough to jump through the same hoops again

tomorrow and tomorrow, for as long

as we have health enough.

It’s a truth stated, and then expanded, with that pleasing reminder of Macbeth in ‘tomorrow and tomorrow’. White’s day-job was teaching literature; it peeps through into her own poems. Emily Dickinson, Byron, Thomas Gray, Shakespeare – all there, with walk-on parts – as well as Housman. Teaching literature includes, of course, introducing students to poetic form – and how better to do that than with an example, as here, where a villanelle is both shown and described in ‘Superfluous Words’ –

The world does not need one more villanelle,

yet teachers still assign the exercise.

Sooner or later someone does it well.

More verses than the damned can read in hell

are written daily; so it’s no surprise

the world does not need one more villanelle.

Reading it with recognition and delight at the supple lines, it’s easy to disregard two lines in the final stanza – ‘What if we fail in trying to excel?/ We’ll all fill coffins of a standard size.’ Almost a throw-away thought – or is it? It’s one of the small way-markers that appear throughout the collection readying the reader for the final section: Leaving. Espaillat has described this well in the introduction, and although at this point she is describing earlier poems it is even more relevant to the final section. She writes: ‘… helps to confirm what I’ve thought for some time now: that the darkest corners of life are often explored most accurately by the so-called “light-verse” poets whose exuberant gift for effortless form teaches them to be nimble with matter as well as manner.’

Leaving opens with ‘Limits of My Knowledge’, a ten-line poem with only one rhyme, and where each couplet ends with a variant on ‘I do not know where things will end.’ The final couplet of this apparently simple poem reads

I’ve seen the way my white cells trend.

I only know that things will end.

Death, interwoven with her own diagnosis of cancer, has a central rôle in the final quarter of the book. Poems in the third person, short-story poems of other lives, surround more personal poems that still hold tight to the wit and observation of the earlier sections. It still crackles. Take ‘Memory Aids’, a prompt-list to disguise possible failures of memory –

These are the things I need to say

to sound as usual on the phone.

The longer I keep my child at bay

the longer my life is still my own.

Independence weaves itself in these poems, too. In ‘Post Diagnosis’ a wife, learning that it is be her (and not him) who will be the surviving partner, allows her face to show ‘an infinite regret’ while – and this is another of those memorable final lines – ‘she plans new uses for his closet space.’ There is no conventional humour in ‘Chemo day’ but the strength of rhyme and metre continues, a way of getting through, of surviving what cancer throws at the poet. Finally, a quiet conclusion, ‘At the Burial of an Abbess’, a graceful withdrawing from the world, written in rhymed triplets so skilfully that the rhyme never intrudes. The final triplets

But what we’ve learned above the ground

is to love silence more than sound,

white more than any colour found.

The work of all our lifetime lets

us look on death with no regrets:

we vanish as the snow forgets.

It might seem an unexpected conclusion to a collection consisting substantially of wit and lightness but this shows White’s control of her poetic skill and her subject: life, in all its aspects. Here is the real wisdom, framed in poetry that remains. The snow might fade; this doesn’t.

This is a collection to read in order, listening to the poems develop their dialogue with each other, and with the reader. White’s ironic and accurate ear is very good company – and this is a very good collection.

Reading Gail White’s collection makes D A Prince think again about some conventional assessments of ‘light’ verse

Wit in poetry is a serious business and a collection of poems using wit in a multitude of forms is even more so. Formal poetry is unforgiving and each slip is magnified by the reader’s expectation; any slip becomes an enormity, towering above those poems whose seemingly effortless lines have slotted together in perfection. Is that why relatively few poets choose to work within the challenges of metre and rhyme? A pitch-perfect ear for the natural tilt and fall of quotidian speech patterns isn’t given to everyone. It isn’t for poets who choose a solitary garret or a lofty mountain top; it’s for those who gossip, eavesdrop, mix at all levels in their communities – poets who get out and about, alert to the everlasting oddities and entertainments of the world. To call it ‘light’ verse doesn’t, quite, capture the blend of skills required to create a short, pithy, perfectly-formed snapshot of human experience, though ‘lightness’ is part of the skill – an ability to float unexpected ideas in accessible forms. Gail White takes her ‘light’ verse seriously but wears her achievements lightly, without pretension. This is a cracker of a collection.

Growing; Working; Holding; Leaving. These headings divide the collection into four near-equal parts and guide the reader. This is ‘life’, roughly – as the opening lines indicate.

So childhood is ‘The Prison’ (the title of this poem) – a reassuringly realistic reminder of what it was like when grown-ups (‘taller gods’) carried on their lofty discussions above our heads. White (and I) belong to that time when children were small, unconsulted, unheard; we were loved but in a somewhat undemonstrative way. We took it for granted that this was what life was like. It’s refreshing to find this openly acknowledged and the dodgy notion of childhood idyll confronted. But the poem’s final line offers our escape route – ‘At any price, grow tall.’ A single sentence, with a spring into the life-after-childhood world. White is good at final lines a a crisp face-up-to-it ending that throws the poem back into the reader’s space.

They are not joke-y, not flip. Clever endings: they don’t close the lid on the poem but linger – and, because White has an ear for the rhythm lying between poems, lead into the next poem. So, for example, the end of ‘Old Photographs’ (above) is followed by ‘Haunted’, the final poem in the Growing section.

One poems tempers another; we (her readers) are given space to make the connection between the love that ends the previous poem and a mother whose presence could be troublesome. ‘A Rolling Stone Gathers Wisdom’, as the opening poem of Working tells us, in a perfect Housman pastiche –

Housman looks so easy to pastiche but he’s not: the flow of ideas has to be uninterrupted, unforced – as it is here. But where is the wisdom? – in the final lines:

In her excellent introduction to this collection, Rhina S. Espaillat calls the final line an ‘almost-placid comment’; it’s the one point on which I disagree with her. For me this is darkly ironic; I can hear a ghostly echo of the pantomime Oh no you haven’t from the reader’s side. It’s two-edged. On one side ‘wisdom’ means not dwelling on death all the time; on the other, we all know we don’t have lots of time. The collection will return to this later, but for now there’s ‘Work’ –

It’s a truth stated, and then expanded, with that pleasing reminder of Macbeth in ‘tomorrow and tomorrow’. White’s day-job was teaching literature; it peeps through into her own poems. Emily Dickinson, Byron, Thomas Gray, Shakespeare – all there, with walk-on parts – as well as Housman. Teaching literature includes, of course, introducing students to poetic form – and how better to do that than with an example, as here, where a villanelle is both shown and described in ‘Superfluous Words’ –

Reading it with recognition and delight at the supple lines, it’s easy to disregard two lines in the final stanza – ‘What if we fail in trying to excel?/ We’ll all fill coffins of a standard size.’ Almost a throw-away thought – or is it? It’s one of the small way-markers that appear throughout the collection readying the reader for the final section: Leaving. Espaillat has described this well in the introduction, and although at this point she is describing earlier poems it is even more relevant to the final section. She writes: ‘… helps to confirm what I’ve thought for some time now: that the darkest corners of life are often explored most accurately by the so-called “light-verse” poets whose exuberant gift for effortless form teaches them to be nimble with matter as well as manner.’

Leaving opens with ‘Limits of My Knowledge’, a ten-line poem with only one rhyme, and where each couplet ends with a variant on ‘I do not know where things will end.’ The final couplet of this apparently simple poem reads

Death, interwoven with her own diagnosis of cancer, has a central rôle in the final quarter of the book. Poems in the third person, short-story poems of other lives, surround more personal poems that still hold tight to the wit and observation of the earlier sections. It still crackles. Take ‘Memory Aids’, a prompt-list to disguise possible failures of memory –

Independence weaves itself in these poems, too. In ‘Post Diagnosis’ a wife, learning that it is be her (and not him) who will be the surviving partner, allows her face to show ‘an infinite regret’ while – and this is another of those memorable final lines – ‘she plans new uses for his closet space.’ There is no conventional humour in ‘Chemo day’ but the strength of rhyme and metre continues, a way of getting through, of surviving what cancer throws at the poet. Finally, a quiet conclusion, ‘At the Burial of an Abbess’, a graceful withdrawing from the world, written in rhymed triplets so skilfully that the rhyme never intrudes. The final triplets

It might seem an unexpected conclusion to a collection consisting substantially of wit and lightness but this shows White’s control of her poetic skill and her subject: life, in all its aspects. Here is the real wisdom, framed in poetry that remains. The snow might fade; this doesn’t.

This is a collection to read in order, listening to the poems develop their dialogue with each other, and with the reader. White’s ironic and accurate ear is very good company – and this is a very good collection.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2017 0 • Tags: books, D A Prince, poetry