Roger Caldwell observes that James Norcliffe makes poetry look deceptively easy

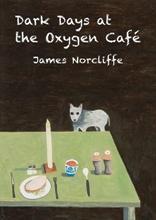

Dark Days at the Oxygen Café

James Norcliffe

Victoria University Press

ISBN 978-1-77656-083-7

80 pp. $25.00

Dark Days at the Oxygen Café

James Norcliffe

Victoria University Press

ISBN 978-1-77656-083-7

80 pp. $25.00

James Norcliffe, the veteran New Zealand poet, deserves to be better-known in this country. His new collection (his ninth) begins with a series of poems labelled ‘Poème Noir’ in homage to the film noir. The opening of ‘Blue’ is in that Gothic mode in which horror metamorphoses into laughter. The rueful narrator confesses: “I should have had my suspicions / when I discovered that she worked / at the National Poisons Centre.” The name Porphyria, and mention of her mass of golden hair, alert us to a poem by Browning in which Porphyria’s lover relates how he comes to strangle her with three strands of that golden hair. In Norcliffe’s poem, however, it is the woman who is the aggressor, and the man who (belatedly) realizes he is in danger. Her hair falls about her shoulders “in such sweet chords and shrouds”. Her eyes are like “fluted phials”. This surely should serve to give warning enough: “How could I be so disposed,” he asks himself finally, “when her lips were half open / and her eyes half closed?” She is not the only woman to be wary of in this group of poems: in ‘Double Indemnity’ Phyllis, likewise with half-open lips, has a crooked finger, and “fastidious nostrils // scenting the death of a husband”. In ‘Uncanny valley’ where “the rocks looked really like rocks” Chloris might be described as only “slightly scary” but she has a problem (or at least, the narrator does) with reality: the solitaire on her finger may be “real” but Chloris’ finger on which it sits is not. (In this short poem no less than three of its lines end with the word “real”.)

Norcliffe is here playing games with appearance and reality. The grand guignol and a sense of the grotesque are never far away. It is hard to say quite how the bald statement that “under a green moon, the visitors / play croquet’ charms with its oddness but that it does so is beyond doubt. Everywhere in Norcliffe’s work there is a narrative urge – we are always in effect being promised a story but that story is at most implied and never quite told.

In the book’s title poem it is language itself that is slippery. It is not clear why the night is said to “creak” or to be “on its very/ last legs” (as the café itself may be) or even less why it should creak “like the battered waiter with / his varicose veins and garlic”. But to the narrator it is the Oxygen Café which fails him – cold where it used to be warm, playing recordings of Seventies music in place of a live pianist, and giving up on linen. Embittered, he protests: “A man shouldn’t have / to live in a world of Kleenex.” Most of all he complains about the lack of gingham. “It’d be on the table,” he remembers from former days, “like a warm cheerful laugh.” Finally he confesses: “God, I loved that stuff.” This nostalgia for gingham has something comical about it – a passion misplaced, one might think – and yet one finds oneself strangely moved by it.

The book’s second section, ‘National Sandfly Day’, also has its misplaced emotions. Why are we called on to commemorate this tiresome pest? The same solemn language we use in respect of soldiers who died in war is here applied to sandflies whose deaths do not usually make us “penitent”. But here, in the title poem of this section, things are otherwise: bare arms and legs are offered up in “atonement for those smudged / millions who have given their lives / for being simply what they were.”

In the remaining three sections of the book – ‘Topiary at the camp’, ‘What do you call your male parent?’, and ‘The White Sea’ – there is no shortage of further surprises, whether these are of the fairy-tale variety (in ‘The big bride’ the problem is simply that the bride has become suddenly and inexplicably too big) or are based on fact (we are referred to the former dictator of Turkmenistan who ordained that the word for bread should be replaced with the name of his deceased mother). Not that he is beyond tampering with the facts if he so wants: in the last poem in the book ‘The Death of Seneca’ the philosopher, commanded to commit suicide by Nero, asks his servants to run a warm bath, to bring him blades, and – somewhat incongruously – pomegranates (which are absent from the famous account of Seneca’s death by Tacitus). There is a certain insouciance in the way Norcliffe re-fashions or re-interprets reality: in ‘Test Flight’ (presumably based on a domestic incident) a child pushes its younger sibling off the roof in a “pillowslip parachute” then gazes on the result. Norcliffe addresses the child:

you must have stood

among the starling feathers

wiser, not necessarily sadder

before you descended the ladder.

Norcliffe’s debts to surrealism – and the tradition of nonsense – are evident in many of these poems. Many of them make one laugh with their wry humour or incongruous juxtapositions. But the thought occurs: How seriously are we meant to take them? And isn’t poetry supposed to be a difficult art? Norcliffe very much eases the readers task. Indeed, I can recall few collections of poetry so compulsively readable as this one is, or so consistently entertaining. With their simple but supple syntax and immediacy of effect these poems draw us into a world where everything seems a little askew – but joyfully so. Nor does he make great claims to philosophical profundity:

I’m a fool but aren’t

we all, wallowing in the sun,

the day, with naught to say

but fol-de-lay, but fol-de-lay?

In a more serious vein ‘By the Arnold’ offers an analogy with fishing: in art you can make the perfect cast and follow through, but it is unclear what (if anything) you will catch: whatever it is, he tells us, “it can only be lost”. Norcliffe is not exactly an opaque writer but he is allusive, and the result is often less translucent than his stripped-down language would suggest. True, he supplies us with notes, but they are sparse, and don’t tell us all we might wish to know. For example, he informs us that omphalomancy is a method of divination by the navel, but doesn’t explain quite how it works. But maybe we don’t need to know. There are always going to be holes in our understanding. Norcliffe offers us something better. French critics once spoke of jouissance in respect of literature. Norcliffe, supreme entertainer that he is, returns us with a vengeance to the pleasures of the text.

Roger Caldwell observes that James Norcliffe makes poetry look deceptively easy

James Norcliffe, the veteran New Zealand poet, deserves to be better-known in this country. His new collection (his ninth) begins with a series of poems labelled ‘Poème Noir’ in homage to the film noir. The opening of ‘Blue’ is in that Gothic mode in which horror metamorphoses into laughter. The rueful narrator confesses: “I should have had my suspicions / when I discovered that she worked / at the National Poisons Centre.” The name Porphyria, and mention of her mass of golden hair, alert us to a poem by Browning in which Porphyria’s lover relates how he comes to strangle her with three strands of that golden hair. In Norcliffe’s poem, however, it is the woman who is the aggressor, and the man who (belatedly) realizes he is in danger. Her hair falls about her shoulders “in such sweet chords and shrouds”. Her eyes are like “fluted phials”. This surely should serve to give warning enough: “How could I be so disposed,” he asks himself finally, “when her lips were half open / and her eyes half closed?” She is not the only woman to be wary of in this group of poems: in ‘Double Indemnity’ Phyllis, likewise with half-open lips, has a crooked finger, and “fastidious nostrils // scenting the death of a husband”. In ‘Uncanny valley’ where “the rocks looked really like rocks” Chloris might be described as only “slightly scary” but she has a problem (or at least, the narrator does) with reality: the solitaire on her finger may be “real” but Chloris’ finger on which it sits is not. (In this short poem no less than three of its lines end with the word “real”.)

Norcliffe is here playing games with appearance and reality. The grand guignol and a sense of the grotesque are never far away. It is hard to say quite how the bald statement that “under a green moon, the visitors / play croquet’ charms with its oddness but that it does so is beyond doubt. Everywhere in Norcliffe’s work there is a narrative urge – we are always in effect being promised a story but that story is at most implied and never quite told.

In the book’s title poem it is language itself that is slippery. It is not clear why the night is said to “creak” or to be “on its very/ last legs” (as the café itself may be) or even less why it should creak “like the battered waiter with / his varicose veins and garlic”. But to the narrator it is the Oxygen Café which fails him – cold where it used to be warm, playing recordings of Seventies music in place of a live pianist, and giving up on linen. Embittered, he protests: “A man shouldn’t have / to live in a world of Kleenex.” Most of all he complains about the lack of gingham. “It’d be on the table,” he remembers from former days, “like a warm cheerful laugh.” Finally he confesses: “God, I loved that stuff.” This nostalgia for gingham has something comical about it – a passion misplaced, one might think – and yet one finds oneself strangely moved by it.

The book’s second section, ‘National Sandfly Day’, also has its misplaced emotions. Why are we called on to commemorate this tiresome pest? The same solemn language we use in respect of soldiers who died in war is here applied to sandflies whose deaths do not usually make us “penitent”. But here, in the title poem of this section, things are otherwise: bare arms and legs are offered up in “atonement for those smudged / millions who have given their lives / for being simply what they were.”

In the remaining three sections of the book – ‘Topiary at the camp’, ‘What do you call your male parent?’, and ‘The White Sea’ – there is no shortage of further surprises, whether these are of the fairy-tale variety (in ‘The big bride’ the problem is simply that the bride has become suddenly and inexplicably too big) or are based on fact (we are referred to the former dictator of Turkmenistan who ordained that the word for bread should be replaced with the name of his deceased mother). Not that he is beyond tampering with the facts if he so wants: in the last poem in the book ‘The Death of Seneca’ the philosopher, commanded to commit suicide by Nero, asks his servants to run a warm bath, to bring him blades, and – somewhat incongruously – pomegranates (which are absent from the famous account of Seneca’s death by Tacitus). There is a certain insouciance in the way Norcliffe re-fashions or re-interprets reality: in ‘Test Flight’ (presumably based on a domestic incident) a child pushes its younger sibling off the roof in a “pillowslip parachute” then gazes on the result. Norcliffe addresses the child:

Norcliffe’s debts to surrealism – and the tradition of nonsense – are evident in many of these poems. Many of them make one laugh with their wry humour or incongruous juxtapositions. But the thought occurs: How seriously are we meant to take them? And isn’t poetry supposed to be a difficult art? Norcliffe very much eases the readers task. Indeed, I can recall few collections of poetry so compulsively readable as this one is, or so consistently entertaining. With their simple but supple syntax and immediacy of effect these poems draw us into a world where everything seems a little askew – but joyfully so. Nor does he make great claims to philosophical profundity:

I’m a fool but aren’t we all, wallowing in the sun, the day, with naught to say but fol-de-lay, but fol-de-lay?In a more serious vein ‘By the Arnold’ offers an analogy with fishing: in art you can make the perfect cast and follow through, but it is unclear what (if anything) you will catch: whatever it is, he tells us, “it can only be lost”. Norcliffe is not exactly an opaque writer but he is allusive, and the result is often less translucent than his stripped-down language would suggest. True, he supplies us with notes, but they are sparse, and don’t tell us all we might wish to know. For example, he informs us that omphalomancy is a method of divination by the navel, but doesn’t explain quite how it works. But maybe we don’t need to know. There are always going to be holes in our understanding. Norcliffe offers us something better. French critics once spoke of jouissance in respect of literature. Norcliffe, supreme entertainer that he is, returns us with a vengeance to the pleasures of the text.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2016 0 • Tags: books, poetry, Roger Caldwell