John Lucas takes an in-depth look at books by Michael Cullup and Gary Allen who both make poetry out of tough experiences

.

Matelot by Michael Cullup

Matelot by Michael Cullup

Greenwich Exchange ISBN: 978-1-906075-958,

132 pp £9. 99

.

.

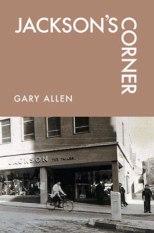

Jackson’s Corner by Gary Allen

Greenwich Exchange ISBN: 978-1-910996-034,

94 pp £9. 99

.

Greenwich Exchange has always had a strong poetry list – David Sutton, John Greening, Marnie Pomeroy, Robert Nye – but its production values now guarantee that it provides some of the best-looking books on the market. Appearances can of course be deceptive, but not in the present instances. The collections of Michael Cullup and Gary Allen under review are both better than good value. They have immediately gripping, well-designed covers, and the subject-matter of both is a long way from conventional without in any sense being tiresomely outre or stylistically inhibiting.

Matelot is by way of being something of a tour-de-force, a long narrative poem about Cullup’s days as a National Serviceman in the Royal Navy. There have of course been a number of memoirs and novels about National Service days, of which David Tipton’s Meal For Malay is probably the best, but as far as I am aware Cullup’s work is a thing unattempted yet in verse or rhyme.

Matelot is by way of being something of a tour-de-force, a long narrative poem about Cullup’s days as a National Serviceman in the Royal Navy. There have of course been a number of memoirs and novels about National Service days, of which David Tipton’s Meal For Malay is probably the best, but as far as I am aware Cullup’s work is a thing unattempted yet in verse or rhyme.

Not that Matelot has Miltonic ambitions. And it is perhaps a little misleading for the blurb to say that the poet-author draws inspiration “from the realistic examples of “Alan Ross, Roy Fuller, Donald Davie and Charles Causley (all of whom had served in the Navy.”) Theirs was after all wartime service, although it has to be said – and Fuller is quick to say it – they saw no action, except from a distance, and Causley, who like Fuller, sailed to foreign parts – Fuller to Africa, Causley to Australia – recorded his findings in what was frankly prentice work. At all events, Farewell Aggie Weston seems to me pretty unmemorable and only worth remarking as the prentice work of someone who would later become a major poet. Ross’s “J.W. 51 B:A Convoy,” on the other hand, about the tedium and, then, horror of war in the Baltic, is one of the defining poems of the war at sea. Although I have written about it at some length in my Second World War Poetry in English, it has been virtually ignored by others, probably because it is a long, semi-continuous narrative.

Two other long poems of war, both major works, have met a similar fate: David Jones’ In Parenthesis and Elegies for the Dead in Cyrenaica, by Hamish Henderson. Quite why narrative poems should so often fall into pools of silence I don’t know, though I could make some guesses, beginning with the reluctance of reviewers to write about more than individual lyric poems –the shorter, the better. Short poems fit on the page. They also produce or are prompted by short attention spans. And they are invariably favoured by those providing the rules for major awards and prizes. “No more than 40 lines.” I hope that Matelot is widely noticed, and perhaps it will help if I note that in his Foreword Cullup remarks that his poem is in some respects almost exotic in its recall of days when seafaring life “was considerably rougher than it is today and compulsory National Service drew on a wider range of character and personality than today’s Royal Navy recruits.” This may raise the odd eyebrow: after all, shipmen from as wide apart in geography and circumstance as Glasgow’s Gorbals and the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth still serve in the Navy, but Cullup is certainly right to say that in the immediate post-war period pub-brawls and street fights among those in uniform were leniently viewed by the public, “many of whom had themselves served in the forces.”

For all that, or perhaps because of it, Matelot is best thought of as a work which is predominantly about “the lower depths”, a term which, (despite Henry Mayhew’s edited transcriptions of life among the nineteenth-century London Poor, Tony Harrison’s best work, and the brilliance of Jon Macgregor’s novel, Even the Dog) has little presence in English life and literature, though it is common enough to writers from other cultures, not merely Gorki, but, to offer a few names at random, the American Nelson Algren, Jean Genet (and’ for that matter, Francois Villon), and the self-taught Greek merchant mariner, Nikos Kavadias. Such depths might suggest lives of inarticulate brutishness, but Cullup, like the writers just named, is excellent at capturing the speech rhythms of those whose talk – and much of Matelot is composed of talk, given both directly and indirectly – is customarily conducted in terse, monosyllabic, half-sentences, often fuelled by the recall of comic, bawdy, roughhouse incidents. “Do you remember” more than one anecdote begins, a formulaic way of kicking open the door into a shared past:

Do you remember Shep's birthday?

He had so much Pusser's rum

it was coming out of his ears.

His part of ship:

Coxswain of the captain's motorboat.

Not my fuckin' favourite.

The short, end-stopped lines are intrinsic to the laconic, half-droll, half-wondering tale of Shep and how on his birthday he became so drunk that he destroyed a boat, “called the Skipper a cunt./ I’ll never fuckin’ forget it,” and ended up in “Portsmouth Naval Prison/with only fifteen months to go./ It doesn’t make fuckin’ sense //…. Reminds me of when Taffy Lewis/hit Captain Royce on Divisions./But that’s another story.”

Most of the anecdotes are like this: they have about them a rather desperate, even innocent, braggadocio, a would-be swagger that can’t disguise the fact that the speaker is more victim than aggressor.

They call it 'sea-time.'

'You got to get your fuckin' sea-time in.

Who wants a fuckin' shore-base, anyway?

Give me a Med, or fuckin' Far Easter, Lofts.

Them Chinese parties fuck like rattle-snakes.

(“Lofts” is the nick-name Cullup is given by his fellow mariners.) As a result, Matelot humanises and makes sympathetic men whose lives are not often allowed into our poetry, unless, that is, it’s by way of making make them a cause. Blessedly free of such condescension, Cullup’s poem is a welcome reminder that, in Louis MacNeice’s words, “world is various and more of it than we know.”

*

Much the same might be said of Gary Allen’s new collection. Here, the focus is on the lives and hard times of working-class Northern Irish people. Fifty years ago, Tony Connor’s first two collections, With Love Somehow and Lodgers, with their witty, tough-minded accounts of working-class life in the north of England, opened up territory that was soon to be occupied by Preston’s Jim Burns and then, to my mind, primus inter pares of all such poets, the Bootle-bom Matt Simpson. “The finest poet of the back-to-backs” Simpson was called by Jeff Nuttall, misleadingly, I think, because Simpson’s subject-matter was by no means confined to the terraced streets of his home city, still less to the glum documentariness that Nuttall’s words imply. W.S. Graham, no easy touch when it came to doling out praise, was far more perceptive when he spoke of Simpson’s being “a special, individual voice speaking from an interesting place … a good hardness coming out of family values and physical working objects … a real special poet.”

Much the same might be said of Gary Allen’s new collection. Here, the focus is on the lives and hard times of working-class Northern Irish people. Fifty years ago, Tony Connor’s first two collections, With Love Somehow and Lodgers, with their witty, tough-minded accounts of working-class life in the north of England, opened up territory that was soon to be occupied by Preston’s Jim Burns and then, to my mind, primus inter pares of all such poets, the Bootle-bom Matt Simpson. “The finest poet of the back-to-backs” Simpson was called by Jeff Nuttall, misleadingly, I think, because Simpson’s subject-matter was by no means confined to the terraced streets of his home city, still less to the glum documentariness that Nuttall’s words imply. W.S. Graham, no easy touch when it came to doling out praise, was far more perceptive when he spoke of Simpson’s being “a special, individual voice speaking from an interesting place … a good hardness coming out of family values and physical working objects … a real special poet.”

Allen’s poems have a similar hardness. And yet. And yet. The insistence on unremitting harshness, inhospitable weather, the sheer rottenness of the lives he writes about, is itself so unremitting as often to feel like one of those misery memoirs which not long ago were all the rage. “Flat Fish” opens:

When I think of those days again –

Blue moons like sailing ships in the sky

The sooty chimneys and the black signature cracks of roof aerials –

It is only to feel again the intense cold:

everything blitzes my mind with its coldness

the backs of the houses where the weak sunlight never reached

but the icy wind could find

the holes in jumpers, school trousers,

socks and soles, that were still washed and hung on the hoarfrost wire-lines ...

“You tell that to the young nowadays,” as the old grumbler in the Monty Python sketch says, “and they’ll not believe you.” No wonder, either. “Blitzes”? Blitz, according to the O.E.D. means “attack, damage, or destroy.” What has been damaged here is credibility, brought about by an overkill of dull adjectives: “intense cold” “weak sunlight” “icy wind.” The blue moons presumably signal unattainable freedom, in place of which the protagonist has to endure a quasi-prison fodder of “uncooked food that congealed to an unpalatable/goo of bread and rice” and, for good measure,

the crack across the lips

and teeth with a wooden baton from the older boy

next door because you were the wrong religion

because he was bored and hungry like you

because his father was on the dole

like yours too...

“Milton could say ‘God damn you to hell,”‘ William Empson told Christopher Ricks, “and make it sing.” However awful the subject matter, he meant, a poet’s responsibility is to his/her craft. There are occasions in Jackson’s Corner when Allen seems to be shovelling out words as a way of enforcing his insistence on the awfulness of it all. But hold hard, I want to cry. Isn’t it all, or anyway some of it, simply factitious. You mean the sunlight was always weak, there was never a mild wind? And cold is enough, already. You don’t need to tell us it was intense. And if Allen replies, but that’s how I remember it, then I want to counter with Lawrence’s remark that tragedy is a great kick at misery. Or, to put it more brutally, stop being so bloody sorry for yourself.

Still, these caveats need to be balanced by praise for the better poems in the collection, some of which are very good indeed. For all his over-determined contempt for, loathing of, or simply belly-aching at, the universe, Allen at his best achieves a spare, taut recording of lost or unachieved lives that doesn’t sink to glumness, but which, odd though it may seem, has about it a saving, even cherishable, humaneness. Hence, the poem “Husks,” which begins “The hardest thing I ever had to do/Was throwing out my mother’s belongings,/ Which wasn’t very much.” At first I wondered whether Allen hadn’t made a grammatical slip, here: doesn’t he mean to say that his mother’s belongings were few? But on reflection I think he’s saying that it wasn’t asking much of him to throw out belongings which revealed her inadequate life – including bras “bought in the local/mass-produced store, plain cotton/with broken clasps and the wire showing.”

Allen is always at his best when directing attention away from himself or at least treating himself with a certain ironic distance. The excellent poem, “California Dreaming,” opens with Allen seemingly in recoil from his subject. “What an ugly man, backstreet scavenger/feet cut with broken glass and stones/from kicking in his own front door”. We’re down among the dead men, but down doesn’t mean out. The poem comes to rest with the man, having survived “five heart attacks” (no, I’ve no idea how Allen knows that) still feeling “California moving through his bowels” and who, battered as he may be, “keeps singing his existence to the rain.” That’s lovely, the iambic pulse that enters the final line registering a subdued, but genuinely defiant exultance.

Something similar happens with the title poem. “Jackson’s Corner” begins: “Somewhere, the sun still shines into Jackson’s Corner/and all the dead are alive again/even those I hated, I now love for having been –” From there, a vista opens out onto memories, personal, familial, social, in a manner saved from soft-focus nostalgia by the allure of its almost musical cadences, the way names and historical moments fall into line:

I am only the body borrowed and passed down

by these ancestors who left no trace,

who buried their children with tradition,

conquerors of the neat grass verges

Thiepval, Milltown, Arlington

and all the great deserts of the world.

The “great deserts” is, I take it, both a sardonic recognition that, as Ozymandias unwittingly demonstrated, all civilisations come to dust, and a more specific testament to the spread of Ulster soldiers in wars across the world. And so to the poem’s ending:

we thought we owned it all

the long afternoon, empty of cars and people

the startled reflections of mannequins caught in the window glass.

To register the full effect of this last, haunting line, you need to see the front-cover image: a photograph of shop window above which you can read JACKSON The Tailor, in front of it a mackintoshed man on a bike signalling to turn right, while the shop’s sunlit side-street wall picks out some dark-suited men lounging at ease. The photograph, like the poem, seems to contain a secret narrative, though whereas the visual image gives us a moment in time, the poem provides a history. The picture says “here we are in all our random oddness.” The poem says, “this is why and how we came to be here. This matters.” It does, too.

John Lucas takes an in-depth look at books by Michael Cullup and Gary Allen who both make poetry out of tough experiences

.

Greenwich Exchange ISBN: 978-1-906075-958,

132 pp £9. 99

.

.

Jackson’s Corner by Gary Allen

Greenwich Exchange ISBN: 978-1-910996-034,

94 pp £9. 99

.

Greenwich Exchange has always had a strong poetry list – David Sutton, John Greening, Marnie Pomeroy, Robert Nye – but its production values now guarantee that it provides some of the best-looking books on the market. Appearances can of course be deceptive, but not in the present instances. The collections of Michael Cullup and Gary Allen under review are both better than good value. They have immediately gripping, well-designed covers, and the subject-matter of both is a long way from conventional without in any sense being tiresomely outre or stylistically inhibiting.

Not that Matelot has Miltonic ambitions. And it is perhaps a little misleading for the blurb to say that the poet-author draws inspiration “from the realistic examples of “Alan Ross, Roy Fuller, Donald Davie and Charles Causley (all of whom had served in the Navy.”) Theirs was after all wartime service, although it has to be said – and Fuller is quick to say it – they saw no action, except from a distance, and Causley, who like Fuller, sailed to foreign parts – Fuller to Africa, Causley to Australia – recorded his findings in what was frankly prentice work. At all events, Farewell Aggie Weston seems to me pretty unmemorable and only worth remarking as the prentice work of someone who would later become a major poet. Ross’s “J.W. 51 B:A Convoy,” on the other hand, about the tedium and, then, horror of war in the Baltic, is one of the defining poems of the war at sea. Although I have written about it at some length in my Second World War Poetry in English, it has been virtually ignored by others, probably because it is a long, semi-continuous narrative.

Two other long poems of war, both major works, have met a similar fate: David Jones’ In Parenthesis and Elegies for the Dead in Cyrenaica, by Hamish Henderson. Quite why narrative poems should so often fall into pools of silence I don’t know, though I could make some guesses, beginning with the reluctance of reviewers to write about more than individual lyric poems –the shorter, the better. Short poems fit on the page. They also produce or are prompted by short attention spans. And they are invariably favoured by those providing the rules for major awards and prizes. “No more than 40 lines.” I hope that Matelot is widely noticed, and perhaps it will help if I note that in his Foreword Cullup remarks that his poem is in some respects almost exotic in its recall of days when seafaring life “was considerably rougher than it is today and compulsory National Service drew on a wider range of character and personality than today’s Royal Navy recruits.” This may raise the odd eyebrow: after all, shipmen from as wide apart in geography and circumstance as Glasgow’s Gorbals and the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth still serve in the Navy, but Cullup is certainly right to say that in the immediate post-war period pub-brawls and street fights among those in uniform were leniently viewed by the public, “many of whom had themselves served in the forces.”

For all that, or perhaps because of it, Matelot is best thought of as a work which is predominantly about “the lower depths”, a term which, (despite Henry Mayhew’s edited transcriptions of life among the nineteenth-century London Poor, Tony Harrison’s best work, and the brilliance of Jon Macgregor’s novel, Even the Dog) has little presence in English life and literature, though it is common enough to writers from other cultures, not merely Gorki, but, to offer a few names at random, the American Nelson Algren, Jean Genet (and’ for that matter, Francois Villon), and the self-taught Greek merchant mariner, Nikos Kavadias. Such depths might suggest lives of inarticulate brutishness, but Cullup, like the writers just named, is excellent at capturing the speech rhythms of those whose talk – and much of Matelot is composed of talk, given both directly and indirectly – is customarily conducted in terse, monosyllabic, half-sentences, often fuelled by the recall of comic, bawdy, roughhouse incidents. “Do you remember” more than one anecdote begins, a formulaic way of kicking open the door into a shared past:

The short, end-stopped lines are intrinsic to the laconic, half-droll, half-wondering tale of Shep and how on his birthday he became so drunk that he destroyed a boat, “called the Skipper a cunt./ I’ll never fuckin’ forget it,” and ended up in “Portsmouth Naval Prison/with only fifteen months to go./ It doesn’t make fuckin’ sense //…. Reminds me of when Taffy Lewis/hit Captain Royce on Divisions./But that’s another story.”

Most of the anecdotes are like this: they have about them a rather desperate, even innocent, braggadocio, a would-be swagger that can’t disguise the fact that the speaker is more victim than aggressor.

(“Lofts” is the nick-name Cullup is given by his fellow mariners.) As a result, Matelot humanises and makes sympathetic men whose lives are not often allowed into our poetry, unless, that is, it’s by way of making make them a cause. Blessedly free of such condescension, Cullup’s poem is a welcome reminder that, in Louis MacNeice’s words, “world is various and more of it than we know.”

*

Allen’s poems have a similar hardness. And yet. And yet. The insistence on unremitting harshness, inhospitable weather, the sheer rottenness of the lives he writes about, is itself so unremitting as often to feel like one of those misery memoirs which not long ago were all the rage. “Flat Fish” opens:

“You tell that to the young nowadays,” as the old grumbler in the Monty Python sketch says, “and they’ll not believe you.” No wonder, either. “Blitzes”? Blitz, according to the O.E.D. means “attack, damage, or destroy.” What has been damaged here is credibility, brought about by an overkill of dull adjectives: “intense cold” “weak sunlight” “icy wind.” The blue moons presumably signal unattainable freedom, in place of which the protagonist has to endure a quasi-prison fodder of “uncooked food that congealed to an unpalatable/goo of bread and rice” and, for good measure,

“Milton could say ‘God damn you to hell,”‘ William Empson told Christopher Ricks, “and make it sing.” However awful the subject matter, he meant, a poet’s responsibility is to his/her craft. There are occasions in Jackson’s Corner when Allen seems to be shovelling out words as a way of enforcing his insistence on the awfulness of it all. But hold hard, I want to cry. Isn’t it all, or anyway some of it, simply factitious. You mean the sunlight was always weak, there was never a mild wind? And cold is enough, already. You don’t need to tell us it was intense. And if Allen replies, but that’s how I remember it, then I want to counter with Lawrence’s remark that tragedy is a great kick at misery. Or, to put it more brutally, stop being so bloody sorry for yourself.

Still, these caveats need to be balanced by praise for the better poems in the collection, some of which are very good indeed. For all his over-determined contempt for, loathing of, or simply belly-aching at, the universe, Allen at his best achieves a spare, taut recording of lost or unachieved lives that doesn’t sink to glumness, but which, odd though it may seem, has about it a saving, even cherishable, humaneness. Hence, the poem “Husks,” which begins “The hardest thing I ever had to do/Was throwing out my mother’s belongings,/ Which wasn’t very much.” At first I wondered whether Allen hadn’t made a grammatical slip, here: doesn’t he mean to say that his mother’s belongings were few? But on reflection I think he’s saying that it wasn’t asking much of him to throw out belongings which revealed her inadequate life – including bras “bought in the local/mass-produced store, plain cotton/with broken clasps and the wire showing.”

Allen is always at his best when directing attention away from himself or at least treating himself with a certain ironic distance. The excellent poem, “California Dreaming,” opens with Allen seemingly in recoil from his subject. “What an ugly man, backstreet scavenger/feet cut with broken glass and stones/from kicking in his own front door”. We’re down among the dead men, but down doesn’t mean out. The poem comes to rest with the man, having survived “five heart attacks” (no, I’ve no idea how Allen knows that) still feeling “California moving through his bowels” and who, battered as he may be, “keeps singing his existence to the rain.” That’s lovely, the iambic pulse that enters the final line registering a subdued, but genuinely defiant exultance.

Something similar happens with the title poem. “Jackson’s Corner” begins: “Somewhere, the sun still shines into Jackson’s Corner/and all the dead are alive again/even those I hated, I now love for having been –” From there, a vista opens out onto memories, personal, familial, social, in a manner saved from soft-focus nostalgia by the allure of its almost musical cadences, the way names and historical moments fall into line:

The “great deserts” is, I take it, both a sardonic recognition that, as Ozymandias unwittingly demonstrated, all civilisations come to dust, and a more specific testament to the spread of Ulster soldiers in wars across the world. And so to the poem’s ending:

To register the full effect of this last, haunting line, you need to see the front-cover image: a photograph of shop window above which you can read JACKSON The Tailor, in front of it a mackintoshed man on a bike signalling to turn right, while the shop’s sunlit side-street wall picks out some dark-suited men lounging at ease. The photograph, like the poem, seems to contain a secret narrative, though whereas the visual image gives us a moment in time, the poem provides a history. The picture says “here we are in all our random oddness.” The poem says, “this is why and how we came to be here. This matters.” It does, too.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, society, year 2016 0 • Tags: books, John Lucas, poetry, society