Pam Thompson finds some bold and resonant poems in a chapbook by Warsan Shire

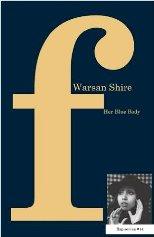

Her Blue Body

Warsan Shire

flipped eye publishing/ flap series

ISBN 978-1-905233-48-9

33pp £7.50

Her Blue Body

Warsan Shire

flipped eye publishing/ flap series

ISBN 978-1-905233-48-9

33pp £7.50

Warsan Shire is a Kenyan-born, Somali writer, poet, editor and teacher. She is London based but has a growing international profile and her work has appeared in a range of anthologies and journals, including the acclaimed Ten: The New Wave (Bloodaxe, 2014). Her début pamphlet, Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth (flipped eye), was published in 2011 and she went on to win the Inaugural Poetry Prize in 2013. The poems in Her Blue Body were written during her tenure as London’s first Young Poet Laureate.

There are 16 poems in the pamphlet, the longest stretching to three pages, the shortest with only four lines. The structure is elegant and arresting: each group of poems is headed by a statement (I’m writing to you from the future to tell you that everything will be okay. I’m sorry you were not truly loved and that it made you cruel. We took such care of tomorrow but died on the way there) which has the appearance of someone’s words, the poet’s perhaps, or those people she talked to during her residency. The statements reverberate throughout our readings of poems which consistently employ metaphor and irony to devastating effect to interrogate – predominantly –female oppression and displacement, mental and physical.

The opening and closing poems ‘ Our Blue Bodies’ and ‘Her Blue Body Full of Light’ are testimonies to friendship and loss. In the first poem we don’t know who it is the poet addresses, but that at once, the nature of the dream suggests a wish to rewind time and to protect and nurture:

I have dreamt of you suspended

in amniotic fluid, your hair fanned out

and alive, long again before the cancer.

There is a suggestion also of being adrift in the space of the mother’s body but also joined via a mutual lifeline:

Undying our movements synchronized,

us, tied together at the navel,

umbilical cord and all its length tugging

at me, far as it might extend.

The closing poem is an metaphorical tour de force, beginning,

Do you believe I have cancer? Yosra asks,

a mug of tea between her hands,

almost laughing, hair cut close to the scalp.

It shifts to a series of comparisons which are both rhapsodic and unexpected, beginning with, I imagine the cancer auditioning/ inside her body … Whoever would have thought of cancer as a potential performance, as a performer who may not get the role. In this poem it performs as light in translucent slivers … needlepoints… fireworks, and is at once burning and cool, water imagery taking us back to the protective space of the womb, deep sea blue inside/ her body, her ribcage an aquarium.

In the final lines light and sound converge and the poem, and the collection, end in transformation and transcendence, her skin glowing and glowing, / lit from the inside.

These are poems that bear witness to horrific events, acts of violence and loss, communicated via personal accounts, effective when distanced and reported as in ‘Photographs of Hooyo’ which proceeds by presenting five snapshots of Hooyoo, followed by a date and place, e.g. 1990, Harlesden, London, including holding negatives up to the sunlight … singing her own Somali/English version of Tracy Chapman’s ‘ Mountains O’things …, culminating with the event that is backdrop to them all which proves that the passing years do not dim painful memories:

Hooyo closing her eyes whenever the reporter says

Mogadishu

on the evening news.

1990-2014,

Harlesden, London.

The understatement is all the more effective. Shire, to great effect, selects and juxtaposes scenes and speech adopting techniques from film. Take ‘Mermaids’. That could be a title of a film but a title, which if taken by itself could not begin to evoke what is evident—quietly, awfully so – from the first lines,

Sometimes it’s tucked into itself,

sewn up

like the lips of a prisoner.

After the procedure, the girl learns

how to walk again, mermaid with new legs …

The scene shifts to the pitiless father,

Daughter is synonymous with traitor …

If your mother survived it, you can.

Cut, cut, cut.

A programme on the television, America’s Next Top Model where the contestants huddle around Amina after her/ confession … to the Mother, it’s not like a heart, you do not die/when they cut it …. The final image, of two girls lying in bed beside each other, holding mirrors/ under the mouths of their skirts,/ comparing wounds, is shocking when we realise that this is not just a picture of normal sexual exploration but that the word wounds reverberates both physically and psychologically.

Female Genital Mutilation (and its consequences) is pervasive; transgressions of the female body, sometimes, startlingly, via testimonies of men:

In the lunchroom, Hussein tells us

what it felt like for him. We’re mesmerised.

Imagine he says, pointing to my mouth,

pushing an entire finger

into the gap

between your front teeth.

The girl beside me shudders …

‘Sara’

In the poem of the same name, Shire relates the conceit of the house to women’s bodies, beginning:

i

Mother says there are locked rooms inside all women; kitchen of lust, bedroom of grief, bathroom

of apathy.

Violation is never far away:

Sometimes, the men—they come with keys,

And sometimes, the men—they come with hammers.

The poem proceeds in a series of ten episodic sections whereby violent undercurrents are displaced via surrealism:

v.

Are you going to eat that? I say to my mother, pointing to my father who

Is lying on the dining table, his mouth stuffed with a red apple.

The poem details the tangles of love and fear that beset a young woman growing up, The bigger my body is, the more locked rooms there are, the more men come with keys. More than that, it enacts a growing separation from the body, the body as house.

ix

Knock knock

Who’s there?

No one

This kind of writing hints at the playwright Warsan Shire might become. A trawl of websites showed that this excellent pamphlet has been barely reviewed, online at least. I hope it has been reviewed in print magazines. These are bold, resonant poems by a significantly talented poet.

.

Pam Thompson is a poet, reviewer and university lecturer based in Leicester. Her publications include Show Date and Time (Smith-Doorstop, 2006) and The Japan Quiz, (Redbeck Press, 2009). She was the 2015 winner of the Magma Poetry Competition’s Judge’s Prize. Pam is one of the organisers of Word!, a spoken-word, open-mic night at The Y Theatre in Leicester.

Pam Thompson finds some bold and resonant poems in a chapbook by Warsan Shire

Warsan Shire is a Kenyan-born, Somali writer, poet, editor and teacher. She is London based but has a growing international profile and her work has appeared in a range of anthologies and journals, including the acclaimed Ten: The New Wave (Bloodaxe, 2014). Her début pamphlet, Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth (flipped eye), was published in 2011 and she went on to win the Inaugural Poetry Prize in 2013. The poems in Her Blue Body were written during her tenure as London’s first Young Poet Laureate.

There are 16 poems in the pamphlet, the longest stretching to three pages, the shortest with only four lines. The structure is elegant and arresting: each group of poems is headed by a statement (I’m writing to you from the future to tell you that everything will be okay. I’m sorry you were not truly loved and that it made you cruel. We took such care of tomorrow but died on the way there) which has the appearance of someone’s words, the poet’s perhaps, or those people she talked to during her residency. The statements reverberate throughout our readings of poems which consistently employ metaphor and irony to devastating effect to interrogate – predominantly –female oppression and displacement, mental and physical.

The opening and closing poems ‘ Our Blue Bodies’ and ‘Her Blue Body Full of Light’ are testimonies to friendship and loss. In the first poem we don’t know who it is the poet addresses, but that at once, the nature of the dream suggests a wish to rewind time and to protect and nurture:

I have dreamt of you suspended in amniotic fluid, your hair fanned out and alive, long again before the cancer.There is a suggestion also of being adrift in the space of the mother’s body but also joined via a mutual lifeline:

Undying our movements synchronized, us, tied together at the navel, umbilical cord and all its length tugging at me, far as it might extend.The closing poem is an metaphorical tour de force, beginning,

Do you believe I have cancer? Yosra asks, a mug of tea between her hands, almost laughing, hair cut close to the scalp.It shifts to a series of comparisons which are both rhapsodic and unexpected, beginning with, I imagine the cancer auditioning/ inside her body … Whoever would have thought of cancer as a potential performance, as a performer who may not get the role. In this poem it performs as light in translucent slivers … needlepoints… fireworks, and is at once burning and cool, water imagery taking us back to the protective space of the womb, deep sea blue inside/ her body, her ribcage an aquarium.

In the final lines light and sound converge and the poem, and the collection, end in transformation and transcendence, her skin glowing and glowing, / lit from the inside.

These are poems that bear witness to horrific events, acts of violence and loss, communicated via personal accounts, effective when distanced and reported as in ‘Photographs of Hooyo’ which proceeds by presenting five snapshots of Hooyoo, followed by a date and place, e.g. 1990, Harlesden, London, including holding negatives up to the sunlight … singing her own Somali/English version of Tracy Chapman’s ‘ Mountains O’things …, culminating with the event that is backdrop to them all which proves that the passing years do not dim painful memories:

Hooyo closing her eyes whenever the reporter says Mogadishu on the evening news. 1990-2014, Harlesden, London.The understatement is all the more effective. Shire, to great effect, selects and juxtaposes scenes and speech adopting techniques from film. Take ‘Mermaids’. That could be a title of a film but a title, which if taken by itself could not begin to evoke what is evident—quietly, awfully so – from the first lines,

Sometimes it’s tucked into itself, sewn up like the lips of a prisoner. After the procedure, the girl learns how to walk again, mermaid with new legs …The scene shifts to the pitiless father,

Daughter is synonymous with traitor … If your mother survived it, you can. Cut, cut, cut.A programme on the television, America’s Next Top Model where the contestants huddle around Amina after her/ confession … to the Mother, it’s not like a heart, you do not die/when they cut it …. The final image, of two girls lying in bed beside each other, holding mirrors/ under the mouths of their skirts,/ comparing wounds, is shocking when we realise that this is not just a picture of normal sexual exploration but that the word wounds reverberates both physically and psychologically.

Female Genital Mutilation (and its consequences) is pervasive; transgressions of the female body, sometimes, startlingly, via testimonies of men:

In the lunchroom, Hussein tells us what it felt like for him. We’re mesmerised. Imagine he says, pointing to my mouth, pushing an entire finger into the gap between your front teeth. The girl beside me shudders … ‘Sara’In the poem of the same name, Shire relates the conceit of the house to women’s bodies, beginning:

Violation is never far away:

The poem proceeds in a series of ten episodic sections whereby violent undercurrents are displaced via surrealism:

The poem details the tangles of love and fear that beset a young woman growing up, The bigger my body is, the more locked rooms there are, the more men come with keys. More than that, it enacts a growing separation from the body, the body as house.

This kind of writing hints at the playwright Warsan Shire might become. A trawl of websites showed that this excellent pamphlet has been barely reviewed, online at least. I hope it has been reviewed in print magazines. These are bold, resonant poems by a significantly talented poet.

.

Pam Thompson is a poet, reviewer and university lecturer based in Leicester. Her publications include Show Date and Time (Smith-Doorstop, 2006) and The Japan Quiz, (Redbeck Press, 2009). She was the 2015 winner of the Magma Poetry Competition’s Judge’s Prize. Pam is one of the organisers of Word!, a spoken-word, open-mic night at The Y Theatre in Leicester.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2016 0 • Tags: books, poetry