John Forth finds that humour is one of the keys to the success of Alberto Torrealba’s tale of a poetic duel (translated by Timothy Adès)

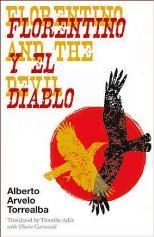

Florentino And The Devil

Alberto Arvelo Torrealba (translated by Timothy Adès)

Shearsman Books, 2014

ISBN 978-1- 848- 613485

116pp £9.95

Florentino And The Devil

Alberto Arvelo Torrealba (translated by Timothy Adès)

Shearsman Books, 2014

ISBN 978-1- 848- 613485

116pp £9.95

From an unsettling place with no shelter or protection (‘El Desamparo’ rendered as trails of misadventure) a man clad all in black rides into view, a man of the road, but of no road. A single bell tolls. We can see that the loose earth at his horse’s footfall / rises up in a dusty cloud and we know it is the height of the dry season. He is pursued over Los Llanos, the plains of Venezuela, by a sinister hoofbeat, a shadow with no face who will challenge him, man against man, to a poetry slam on the world’s black edge. This opponent, who has heard of the famous rider-poet, will turn out to be the Devil, another great singer and poet, here cast as an Amerindian, one of the original inhabitants of Los Llanos.

Ring any more bells? It shouldn’t, unless you are familiar with the opening to El Contapunteo de Florentino y el Diablo, 1300 lines of quick-fire dueling in which the first line of each section repeats the final line of the one preceding to produce a new riddle. Torrealba was a Venezuelan plainsman poet, educator and lawyer who retired from political life in 1955, at the age of fifty, to devote himself to an already substantial literary career. Timothy Adès is a translator of Spanish, French, German and Greek, specialising in rhyme and metre. The rhyme-sound is changed eight times in Spanish – and many more times in Adès’ English version – leaving no doubt of the swingeing virtuosity involved in handling such a form at all, in either language. Each character will make use of the rhyme-change to wrong-foot the other in the contest. With the acknowledged help of Gloria Carnevali, the extensive notes at the end give some sense of a language and a land more redolent of political and social history than we are perhaps accustomed to. It is a fascinating take on the Faustian pact even before the riddling begins.

The Devil’s first five questions, typical of the Llaneros, embrace cock-fighting (or politics); politics; music; riding and the problem of dealing with thirst on the dry plains. In the first scene, Florentino had been mysteriously deprived of water from an obviously real source, and the Devil later wants him to own up to this. The reply is, loosely, that the devil may never drink whereas the mortal man was deprived just the once. The Devil will later warn that pretty speeches won’t do:

Art fades without folk

like the smoke from a train:

it must tread the hot earth,

raising dust for the brain… (508-11)

Otherwise, says the Devil, the poet will lose heart and dry up. Florentino’s reply is an appeal to his own superiority: Who both sings and plays / retains the advantage (550-1). It is soon evident this material is both deep as the lonesome dunes and superficial as birdsong, and there are twenty-two birds still to meet in the final thousand lines, another tradition of Llanero song. The whole will be threaded with moments of startling wisdom woven into a rigid structure, and much of it bears the weight of poetic manifesto. Florentino, prompted by the Devil’s initiative, asserts:

Which songster is better:

the one who deals daily

to barter his labour,

not poking his nose in… (416-19)

After another bout of more-or-less cheap taunting and counter-blast, Florentino will remind him:

What I’ve taught, I have kept,

what I’ve learnt, I’ve forgotten. (754-5)

.

When the poet says he is sustained by his star of eternal faith, the Devil replies: Eternity’s common, like hating and loving (887-8). Poets are known to make nothing happen, of course, and people in bad times want gold or honey rather than doggerel. The singer replies,

These clouds cast no chill

if on two feet one goes,

not reckoning woes,

recounts his goodwill,

and keeps his best tale

for telling to you… (941-46)

To reinforce the idea, Florentino is not even shy of criticizing the Devil’s technique:

Bell-clappers aren’t happy

when ringers hang clowning.

Art, even in heaven,

is all disciplining:

archangels sing flat when

conductor’s gone swanning. (991-96)

The Devil’s final warning of eternal suffering as sunrise approaches, signalling the end of the contest, is answered by Florentino’s invocation of divine powers, principally Our Lady, in various forms and guises, which the Devil calls cheating. He’s not happy. There could easily (well, perhaps not that easily) be a sequel.

If at times the piece reads like one of those comic scenes in Shakespeare where the replies and retorts depend upon word-play we’ve all forgotten, or perhaps never knew, there’s still enough in it to interest anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry. But it also occurred to me that, as with Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, nothing works unless the humour works, and in Florentino it most emphatically does work. You get the feeling straight away of an extraordinary depth and resonance in this complex and down-to-earth poem.

John Forth grew up in Bethnal Green and now lives by the sea in North Somerset. Low Maintenance: New & Selected Poems was published by Rockingham in Spring 2015 (and has recently been reviewed on London Grip).

John Forth finds that humour is one of the keys to the success of Alberto Torrealba’s tale of a poetic duel (translated by Timothy Adès)

From an unsettling place with no shelter or protection (‘El Desamparo’ rendered as trails of misadventure) a man clad all in black rides into view, a man of the road, but of no road. A single bell tolls. We can see that the loose earth at his horse’s footfall / rises up in a dusty cloud and we know it is the height of the dry season. He is pursued over Los Llanos, the plains of Venezuela, by a sinister hoofbeat, a shadow with no face who will challenge him, man against man, to a poetry slam on the world’s black edge. This opponent, who has heard of the famous rider-poet, will turn out to be the Devil, another great singer and poet, here cast as an Amerindian, one of the original inhabitants of Los Llanos.

Ring any more bells? It shouldn’t, unless you are familiar with the opening to El Contapunteo de Florentino y el Diablo, 1300 lines of quick-fire dueling in which the first line of each section repeats the final line of the one preceding to produce a new riddle. Torrealba was a Venezuelan plainsman poet, educator and lawyer who retired from political life in 1955, at the age of fifty, to devote himself to an already substantial literary career. Timothy Adès is a translator of Spanish, French, German and Greek, specialising in rhyme and metre. The rhyme-sound is changed eight times in Spanish – and many more times in Adès’ English version – leaving no doubt of the swingeing virtuosity involved in handling such a form at all, in either language. Each character will make use of the rhyme-change to wrong-foot the other in the contest. With the acknowledged help of Gloria Carnevali, the extensive notes at the end give some sense of a language and a land more redolent of political and social history than we are perhaps accustomed to. It is a fascinating take on the Faustian pact even before the riddling begins.

The Devil’s first five questions, typical of the Llaneros, embrace cock-fighting (or politics); politics; music; riding and the problem of dealing with thirst on the dry plains. In the first scene, Florentino had been mysteriously deprived of water from an obviously real source, and the Devil later wants him to own up to this. The reply is, loosely, that the devil may never drink whereas the mortal man was deprived just the once. The Devil will later warn that pretty speeches won’t do:

Otherwise, says the Devil, the poet will lose heart and dry up. Florentino’s reply is an appeal to his own superiority: Who both sings and plays / retains the advantage (550-1). It is soon evident this material is both deep as the lonesome dunes and superficial as birdsong, and there are twenty-two birds still to meet in the final thousand lines, another tradition of Llanero song. The whole will be threaded with moments of startling wisdom woven into a rigid structure, and much of it bears the weight of poetic manifesto. Florentino, prompted by the Devil’s initiative, asserts:

After another bout of more-or-less cheap taunting and counter-blast, Florentino will remind him:

.When the poet says he is sustained by his star of eternal faith, the Devil replies: Eternity’s common, like hating and loving (887-8). Poets are known to make nothing happen, of course, and people in bad times want gold or honey rather than doggerel. The singer replies,

To reinforce the idea, Florentino is not even shy of criticizing the Devil’s technique:

The Devil’s final warning of eternal suffering as sunrise approaches, signalling the end of the contest, is answered by Florentino’s invocation of divine powers, principally Our Lady, in various forms and guises, which the Devil calls cheating. He’s not happy. There could easily (well, perhaps not that easily) be a sequel.

If at times the piece reads like one of those comic scenes in Shakespeare where the replies and retorts depend upon word-play we’ve all forgotten, or perhaps never knew, there’s still enough in it to interest anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry. But it also occurred to me that, as with Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, nothing works unless the humour works, and in Florentino it most emphatically does work. You get the feeling straight away of an extraordinary depth and resonance in this complex and down-to-earth poem.

John Forth grew up in Bethnal Green and now lives by the sea in North Somerset. Low Maintenance: New & Selected Poems was published by Rockingham in Spring 2015 (and has recently been reviewed on London Grip).

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2015 0 • Tags: books, John Forth, poetry