*

This issue of London Grip New Poetry features poems by:

*Teoti Jardine *Carol DeVaughn *Michael Lee Johnson *John Snelling *Robert Nisbet

*Louise Warren *Jennie Christian *Ricky Garni *Kate Foley

*Christopher Mulrooney *Ian C Smith *Shanta Acharya

*Jennifer Johnson *Ruth Bidgood *Robert Chandler

Copyright of all poems remains with the contributors

A printer-friendly version of London Grip New Poetry can be obtained at LG new poetry Spring 2014

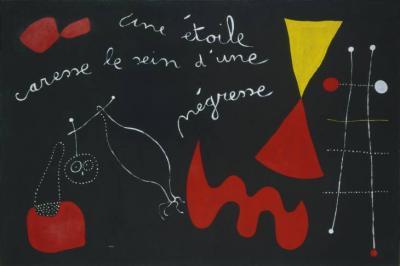

‘Ladder of Escape’ – Joan Miro

‘Ladder of Escape’ – Joan Miro

Please send submissions for the future issues to poetry@londongrip.co.uk, enclosing no more than three poems and including a brief, 2-3 line, biography

Editor’s Introduction

The spring edition of London Grip New Poetry begins with a meditative – almost mystic – response to the present crisis in Syria and ends with some fine atmospheric translations of poems from early twentieth-century Russia. En route from one to the other, the reader will encounter poems which touch on the Cold War period with its protest songs and its actual protests. It is good to be reminded that poetry is able to deal with wider issues of history and politics as well as with currently-felt experiences and personal recollections. Of course, private memories, both poignant and bizarre, do also figure among the poems which follow, as do out-and-out works of fantasy. In compiling this varied selection it has been a pleasure to receive submissions from (and sometimes to converse with) poets in many parts of the world. Some of our authors are making repeat appearances while others are first-timers. It has been particularly encouraging to receive work from poets who are previously unpublished – when one of these new voices displays a strong individuality. It is to be hoped that readers will enjoy reading this issue as much as the editor enjoyed seeing it take shape.

*

Shortly before this introduction was written we heard the sad news of the death of Sebastian Barker. He will be widely remembered for his fine, reflective poetry, which often made skilful use of rhyme and form, and for his perceptive and encouraging editorship of The London Magazine. The many tributes paid since his death show that he will also be much missed as a warm and generous human being. (Helen Donlon’s thoughtful article about Sebastian Barker’s childhood can be found at https://londongrip.co.uk/2012/02/an-arcadian-literary-childhood-in-tilty/)

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

http://mikeb-b.blogspot.com/

Back to poet list… Forward to first poem

***

Teoti Jardine: Syria

The wind remembers

the promise

of the touching.

The resounding

response,

YES.

Waves chanted

upon the shore,

remember.

We had pleaded,

allow us to

become,

we were asked,

will you

remember,

yes we cried,

we will

remember.

Permission given,

the BE

sounded.

The place,

perfectly

prepared.

All the names,

mirrored within

us.

How easily we

succumbed to

ownership.

Tasting beauty,

our longings

aroused,

and found

release in

lordship-ness.

We had chorused

YES, left it

unrequited.

That YES, still resides,

these times our

readying.

Cranes and geese

cast their shadows

on the desert,

where each grain

of sand, knows

it is not other.

.

Teoti Jardine was born in Queenstown New Zealand, of Maori, Irish and Scottish descent. His tribal affiliations are Waitaha, Kati Mamoe, and Kai Tahu. He completed the Hagley Writers Course in 2011, and has poetry published in The Christchurch Press, The Burwood Hospital News Letter, London Grip, Te Panui Runaka, Te Karaka, and Ora Nui. His short stories have been published in Flash Frontier’s International Issues, 2013

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Carol DeVaughn: Rain

If rain could speak

it would tell us the history

of its downpours -

the stories of lives

that stream into ours

how its water rises

in clouds and mists

carrying a memory

of the dead

and the living

like lovers sleeping

in meadow grass;

how it falls

on unknowing houses,

makes harmonies

along roofs and walls,

wakes somnambulant air

from its spell,

sweeps away nightmares,

strives to make spheres

on windowpanes.

It remembers the meadow grass

and the felicity of molecules.

.

Carol DeVaughn, American-born, has been living and working in London since 1970. Retired from full-time teaching, she is now preparing her first full collection. Her poems have appeared in magazines and anthologies and she has won several prizes, including a Bridport in 2012.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Michael Lee Johnson: Rainbow in April

April again,

the wind

falls in love with itself

skipping across asphalt

and concrete bare

with the breaking weather

A rainbow

is half arched,

broken off deep

into the aorta

of the gray sky.

It hangs

as if from

rubber bands

its mixed colors

drawn from God’s

inkwell,

and brushed

by the fingertips

of Michelangelo.

April again,

the wind steps high.

A rainbow

is half arched,

broken off deep

into the aorta

of the gray sky.

It hangs

as if from

rubber bands

its mixed colors

drawn from God’s

inkwell,

and brushed

by the fingertips

of Michelangelo.

April again,

the wind steps high.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Michael Lee Johnson: Red Rocking Chair

A red rocking chair abandoned in a field

of freshly cut clover,

rocks back and forth-

squeaks each time

the wind pushes

at its back,

then,

retreats.

abandoned in a field

of freshly cut clover,

rocks back and forth-

squeaks each time

the wind pushes

at its back,

then,

retreats.

.

.

.

Michael Lee Johnson lived ten years in Canada during the Vietnam era. Today he is a poet, freelance writer, photographer who experiments with poetography (blending poetry with photography), and small business owner in Itasca, Illinois. He has been published in more than 750 small press magazines in 26 countries. He edits 7 poetry sites and is the author of The Lost American: From Exile to Freedom, several chapbooks of poetry, including From Which Place the Morning Rises and Challenge of Night and Day, and Chicago Poems. He also has over 69 poetry videos on YouTube.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

John Snelling: The Shop

It’s the shop you always passed

in childhood;

parents hurrying on

elsewhere.

A window full of promises,

the entrance small,

but you always knew

that inside it went on forever.

You never forgot it

but never could recall

exactly where it was.

Once or twice, as an adult,

you returned

but couldn’t find it.

It’s not there anymore.

Maybe, it never was.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

John Snelling: Journey With No Virgil

Young and uneasy amid wrecked buildings, new towers,

in war-scarred London.

Hearing the talk of bombs.

Learning to fear

The Bomb.

Schooled to appease an angry vengeful God,

trinity of Jornado del Muerto.

Lost at the beginning of life’s way

in a shadowed metal forest.

War grew cold.

‘All hope abandon’ said the sign;

protest and rebellion our response.

We thought our parents stiff misguided fools,

that love was all you need,

that we could fix a shattered world

with slogan and sit-in.

We joined, we followed, waved our banners high

and we sang in the streets as we marched.

Jornado del Muerto: The name of the desert area in which the first atomic bomb test was carried out. The test was codenamed ‘Trinity’. The name of the valley means ‘journey of the dead man’.

.

John Snelling has been writing poetry since the 1960s. In 1976, he won first prize in the City of Westminster Arts Council’s poetry competition. After this, success in competitions eluded him until, in 2013, he gained a Judge’s Special Commendation in The Poetry Box competition for dark and horror poetry.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Robert Nisbet: A Period Piece

In Martha’s kitchen, steam and the smell of soap.

Hot tea and biscuits. She and Jean

plucking the threads of a small town’s week.

Now there’s a pair of silly sods. Students.

That boy Nesbitt and that Wynne Whatsisname,

in the Grey Hart Café, thumping that boy’s guitar.

These fancy songs, The Times Are Changing,

We Will Overcome, and that Bob Dylan-Thomas.

So Lorna asks them, What are you singing, boys?

and, sarky-like, What is your message?

So that Nesbitt says, We’re singing of brotherhood,

Mrs. Davies, and love and peace. The cheeky beggar.

So Lorna, quick as a flash, says,

Do they have sisters in these brotherhoods?

Or will you boys run the world? Joking, like.

But that flattened them. The two daft lumps.

So, every thread inspected,

looked at for size and grain and story’s truth

and lingered over in the scent of tea,

in the peace of Martha’s kitchen.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Robert Nisbet: Joan and Alice in the Seafront Café

The café’s plain, looks out upon

the dock, the wide blue harbour.

Joan and Alice, in mid-morning cups,

are reminiscing of the present day.

I listen, see the photos passed across.

And this is Bernard by the uni library ….

(On to his room, his hall of residence) …

And this is Bernard’s girl friend …

(Subdued frisson and I fancy

she’ll be mini-skirted well up-thigh.)

The picture spread continues:

the lecture halls, the campus and the Summer Ball …

He’s done well, your Bernard, hasn’t he?

A credit to you, Joanie.

He thinks he might do advertising.

He’ll go far, that boy, go far.

Sleet drizzles on the café’s window,

in from the dock and the big bay,

out to the wide blue distances

where Bernard’s father once

trawled heavy waters to the West and North,

the Irish Sea, the Hebrides, the storms.

Robert Nisbet was for several years an associate lecturer in creative writing at Trinity College, Carmarthen, where he also worked for a while as an adjunct professor for the Central College of Iowa. His short stories appear in Downtrain (Parthian, 2004) and his poems in Merlin’s Lane (Prolebooks, 2011).

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Louise Warren: Alice and the hornet

Insistent as an unloved uncle, drunken,

bumping back and forth from his brightly lit doorway,

that pouch of poison bulging between his whiskered legs.

He makes one last lunge towards her, into the air,

you are so young and beautiful he growls,

I want to wrap myself in your hair.

I want to burrow deeper into those hot dark drifts.

She is on her feet now, feeling him, elderly pupa,

crawling back to infancy.

You are so warm, he croons, my love,

just let me.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Louise Warren: Balconies

One by one we step out into the mild London night,

and lean our arms against the white railings.

The trees are huge now, engulfing the square like barrage balloons.

They creak and sway, billowing their black silks.

There is a tension in the air, someone shouts out,

something like a plea and our hands loosen for a moment,

distracted by the voice, the wind, the strange

black silks straining against their ropes.

Look at us, just scraps holding onto the edge with our fingertips.

Louise Warren won the Cinnamon Press First Collection Prize and her book A Child’s Last Picture Book of the Zoo was published in 2012. She has also been widely published in magazines and anthologies including Agenda, Envoi, Fuselit, Genius Floored Poetry Anthology, The Interpreters House, The New Writer, Orbis, Obsessed with Pipework, Poetry Wales, The Rialto, Seam and Stand. In 2013 her poems were highly commended for both the Ver and Yeovil Poetry Prize.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Jennie Christian: It was labelled ‘Mellow’

An apple is sitting beside me on the sofa.

Its rosy glint catches my eye

as if it’s trying to tell me something.

She told me not to take too much at once, that girl in Amsterdam.

So why did I put all of that sachet into our pesto for lunch?

And where’s S? He was here 10 seconds ago.

The room is the wrong shape.

A buzz creeps around the top of my skull, smelling of bacon.

My watch says 5.40pm. Some years later, it says 5.45pm.

Must get a grip.

Eat something?

An apple would be nice I’ll get one from the kitchen oh no there’s one right here

I’m scared I want my old brain back this one is overflowing

endless thoughts chase each other down endless tunnels

and there’s no way out no way no

Somewhere a dog is barking

She has difficulty understanding the dog who speaks poor English

Everything is Falling into a Crevice of your Mind

the room is now a giant Pumpkin

and i am on the Inside trying to rip myself Out

phone rings my sister can’t understand what she says

please come over, come right now

I want to say but words are jumbled spaghetti stuck in neverendingtangle

can’t remember wheresentencestarted whatsentence nosense nonsense

oh god oh my god help me

Go on the balcony, get some air. That will help. Then just glide off

into the breeze. Up, up, up...

No no no someone will come and take me away must do something anything

I take a bite of apple,

which laughs crunchily. Its words are perfectly clear.

What did I tell you, dopehead?

.

Jennie Christian is based in London. Her poems have appeared (or are due to) in poetry journals and magazines including Agenda Poetry (Rilke issue 2007, online supplement), Orbis Quarterly International Literary Journal (#162 Winter 2012-13), SOUTH (issue 48, October 2013) and Obsessed with Pipework (January 2014); also several anthologies

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ricky Garni: Foods That Are Good For Dry Skin

I look at an avocado, split and sundered

and I don’t think of a hazel vulva.

I think of my banana-colored Volvo,

which exploded in the parking lot–

it frightened the elderly ladies nearby who

were wearing vulvas and already crying.

I look at salmon, and I think: where

is the lemon and ice? Where is the fine

sweater that you once told me to find,

salmon hued, and I explained forthwith

that I had left it in the truck with a man

with a gun named Jedidiah whose

manner was vulgar? It was a flatbed

truck, filled with ice and lemon,

and it was a dream. A dream of

Jedidiah’s, or am I dreaming

of Jedidiah’s dream? Am

I just a dream of Jedidiah?

Who knows?

I look at a sweet potato, and

I think to myself: what is wrong

with this world? Why can’t we

all just get along? And then

I eat a sweet potato.

.

Ricky Garni is a writer and designer living in North Carolina. He is presently completing a collection of tiny(I mean, these are teensy tiny!) poems entitled What’s That About, dutifully banged out on Faye Hunter’s 1971 Smith Corona typewriter in purple cursive typeset, and dedicated with great affection to her memory.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Kate Foley: Money To Burn

This is what you burn for the dead

if you're Chinese. Little packets

of gold foil. They curl up, baby dragons,

stretching in the flame of their lives,

and go out diminuendo, like ash flakes.

In the west we have fireworks, which nobody

connects with dying: cop-drama bangs.

But the sudden rain of sparks,

like golden umbrella spokes opened

in the sky is fresh as rain itself.

As fresh as the pathos of things

that don't know they're discarded,

the lumpy blue of tightfisted mussel shells

now open, the lace's gracile fall

from a dead shoe.

It's a bit like gold Chinese money

poked into the stiff hands of the departed

with guilty love. You can't help

feeling a stab of pleasure that your heart

is live enough to quiver as bank notes

curl in the borrowed life of fire.

.

Kate Foley‘s 5th full collection One Window North was published by Shoestring Press in 2012. She lives, writes and leads workshops between Amsterdam and Suffolk.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Christopher Mulrooney: grotto

you can’t miss the thing at all

there’s the street it goes right by

and there the town square you pass along

and suddenly there’s the place

look here you plump you down

I say are you mad quite folly-cast

took sick blind as any shrieking bat

well take out your money here and now

when the morning stars sang they emptied their filth into this place

now have you seen my will in the matter

there is them as wants it shall not have it

you and I have a lot of ground to cover

is it really as hard as all that

come have you squinted or lollygagged

instead of using your wits have you tried

well then here’s your tea and slop be content

go ahead and take a look now it won’t harm you

that’s it with you taking a look we’ll have you settled

and all this place now very soon

a place for everything and everything in its place

you do not bargain very well my friend

if you do not have me well do you have nothing

you know very well what you have and bear it

there’s an end laid on you have you know your just deserts

do not mistake this for a place of anomaly

you know it for what it is a grotto nothing more

many more like it every day so do your work

be glad and health and fitness attend you labouring

what is this a garden where the gardener

yes that’s a story for another day

what I shall say for this while is

have a care remember our first meeting

that is all that’s enough and if our journeys end

they meet as meet we now and thus complete

the peril and the passing time in joy as well

as wishing for abandon and reflection there

so there a record of these beginnings and endings

with the great arc in the middle they teach at school

state your purpose and leave your name at the door

you’ll have reached the institution in some degree

Christopher Mulrooney has written poems in The Hour of Lead, Black & BLUE, The Cannon’s Mouth, The Seventh Quarry, SAND Journal, Red Branch Journal, The Germ, Auchumpkee Creek Review, Epigraph Magazine, West Wind Review, Pomona Valley Review, TAB: The Journal of Poetry & Poetics, Or, pacific REVIEW, and The Criterion.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ian C Smith: Abattoir Road

These several cherished rooms I call my own

in which I read, think, watch the sun

emerge through gently rising river fog,

the tired dusty chair, the reading glasses

that mark my place in second-hand books,

form the mute rhythm of serene days.

A slew of years all over me, I think of a life

far from how I always meant to live.

Winter, smells of steel and cooking fat.

A boy caught a train without a ticket,

thin sleeves rolled to disguise frayed elbows.

He would haul dirty laundry in a bag

to his sister, already blindly fugitive

from meanness into another lifetime trap.

Sometimes he took long walks from a rented room,

his only option after family meltdown.

I interrogate scars on my inked skin,

this palimpsest of hungry, dangerous times

on lean streets where he dwelt,

petrol fumes overlaid by cigarette smoke,

grey windows masking violence and sorrow.

Though it took so long to journey from

that rude room, no fit place for a child,

a cathedral choir of ideas now supersedes rage.

.

Ian C Smith’s work has appeared in Axon:Creative Explorations,The Best Australian Poetry, London Grip, Poetry Salzburg Review, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, The Weekend Australian & Westerly. His latest book is Here Where I Work from Ginninderra Press (Adelaide). He lives in the Gippsland Lakes area of Victoria, Australia.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Shanta Acharya: Ladder of Escape

For Joan Miro

A time for retreat

to a world imagined

perhaps a river made iridescent

by the passage of a swan

a time to rise above

the incompleteness

of life, understand emptiness

invisibility, liberation

discover magic ladders

wander in rapture, peace

towards the rainbow

guided by phosphorescent

tracks of tortoises

leaving behind individuality

plunging into anonymity

a star caressing the breast of happiness

casting off cobwebs of prejudices

prisons built by us, our past selves…

celebrating creation

a negation of negations

drawing with smoke on air

free, magical things

connecting earth to sky

becoming a tree with ears, eyes

a drop of dew falling from

the wing of a bird

in answer to a prayer

prophetic, a ladder of escape.

.

Shanta Acharya was born and educated in India before studying at Oxford and Harvard. The author of nine books, her latest poetry collection is Dreams That Spell the Light (Arc Publications, UK; 2010). Her poems, articles and reviews have appeared in major publications including Poetry Review, London Magazine, and The Spectator. She is the founder director of Poetry in the House, Lauderdale House in London, where she has been hosting monthly poetry readings since 1996. She was elected to the Board of Trustees of the Poetry Society, UK, in 2011. www.shantaacharya.com

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Jennifer Johnson: Holiday

My heart sinks into the sand

they’ve just returned from.

Their relentless prattle

gets me: hassle, slums,

hopeless food, no English.

The beach, it seems,

was disappointing,

full of hawkers and thieves.

It looked lovely, they said,

when the agent showed them

photos in early March.

So, they were sold

a truly utopian beach,

virgin golden sand

free from the dark ash

of history or politics,

without the corrugated iron

too many lives rust under

or the desperation for notes

from the purses of strangers

who want photos of paradise

and what’s needed for a tan.

Jennifer Johnson. has had poems published in several magazines including Acumen, The Frogmore Papers, The Interpreter’s House, Obsessed with Pipework, Orbis, Poetry Salzburg Review, The SHOp, South and Stand and a pamphlet published by Hearing Eye (Footprints on Africa and Beyond, Hearing Eye, 2006).

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ruth Bidgood: Undefined

Probably this photograph

is of the woman, though

she is so small, so far,

she could be incidental.

From the road above

a grassy slope, she seems

to be looking down at him.

His lens is turned towards her,

but doesn’t zoom in

to lessen the distance between them.

That may be the subject –

distance: the small figure

below sombre crags

above the long steep drop

to the river.

No certainty

of any interchange;

maybe a look? Maybe.

Only the lens,

making its moment’s précis,

has definition.

The hinted story has none.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ruth Bidgood: Wrong Turn

I should not have been there,

shall not be there again,

shall not forget.

The lane

meandered through a thin wood,

went on too long, brought conviction

only of trespass.

Suddenly

the trees sat back, lane

became drive, pillared bridge

led to gravelled forecourt.

Long, low, redly creepered

in September sun,

the house glowed.

No sound except a river’s

understated calm-weather song.

From the bridge, deep shadow.

A mill down there, huge wheel

motionless, seeming not disused

but resting from use,

workaday, but in that dimness

not without mystery. I realised

it was the Wye that flowed

as millstream here, queen

playing handmaid.

Looking back

at the house before leaving,

unexpectedly I felt kinship

between its life and mine, both

being contradictory, unclear.

It lived on two levels, plunged

from sun to shade; was hard in stone,

in water, shifting, mutable.

It had a kind of certainty, yet endured

tremors of hauntedness.

This place

had been intruded on, and yet had taken

me, chance-come questioner,

into its unknown story; destined

to stay in mine, had made an entry,

unwilled, uninvited, welcome.

.

Ruth Bidgood lives in Mid-Wales.. She has published 13 books of poems, and one prose book about the Abergwesyn area of old North Breconshire, which was her home for many years. She also contributes research articles to county journals In Powys and Carmarthenshire.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Robert Chandler: Translations of poems by Alexander Alexandrovich Blok

She came in out of the frost

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok 6 February 1908, tr. Robert Chandler

She came in out of the frost

her cheeks glowing,

and filled my whole room

with the scent of fresh air

and perfume

and resonant chatter

that did away with my last chance

of getting anywhere with my work.

Straightaway

she dropped a hefty art journal

onto the floor

and at once

there was no room any more

in my large room.

All this

was somewhat annoying,

if not absurd.

Next, she wanted Macbeth

read aloud to her.

Barely had I reached

the earth’s bubbles

which never fail to entrance me

when I took in that she,

no less entranced,

was staring out of the window.

A large tabby cat

was creeping along the edge of the roof

towards some amorous pigeons.

What angered me most

was that it should be pigeons,

not she and I,

who were necking,

and that the days of Paolo and Francesca

were long gone.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

When you stand in my path

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok 6 February, 1908, tr. Robert Chandler

When you stand in my path,

so alive, so beautiful,

yet so tormented;

when you talk only of what is sad,

when your thoughts are of death,

when you love no one

and feel such contempt for your own beauty –

am I likely to harm you?

No… I’m no lover of violence,

and I don’t cheat and am not proud,

though I do know many things

and have thought too much ever since childhood

and am too preoccupied with myself.

I am, after all, a composer of poems,

someone who calls everything by its name

and spirits away the scent from the living flower.

For all your talk of what is sad,

for all your thoughts of beginnings and endings,

I still take the liberty

of remembering

that you are only fifteen.

Which is why I wish

you to fall in love with an ordinary man

who loves the earth and the sky

more than rhymed

or unrhymed

talk of the earth and the sky.

Truly, I will be glad for you,

since only someone in love

has the right to be called human.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

from ‘Dances of Death’

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok 10 October 1912, tr. Robert Chandler

Night, lantern, side-street, drug store,

a mindless, pallid light.

Live on for twenty years or more –

it’ll be the same; there’s no way out.

Try being reborn – start life anew.

All’s still as boring and banal.

Lantern, side-street, drug store, a few

shivering ripples on a canal.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

from ‘The Twelve’

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok January 1918, tr. Robert Chandler

From street to street with sovereign stride…

– Who’s there? Don’t try to hide!

But it’s only the wind playing

with the red banner ahead.

Cold, cold, cold drifts of snow.

– Who’s there? No hiding now!

But it’s only a starving hound

limping along behind.

Get lost, you mangy cur –

or we’ll tickle you with our bayonets.

This is the last of you, old world –

soon we’ll smash you to bits.

The mongrel wolf is baring his fangs –

it’s hard to scare him away.

He’s drooping his tail, the bastard waif…

– Hey, you there, show your face!

Who can be waving our red banner?

Wherever I look – it’s dark as pitch!

Who is it flitting from corner to corner

always out of our reach?

– Doesn’t matter, we’ll flush you out.

Better give yourself up straightaway!

Quick, comrade – you won’t get away

when we start to shoot!

Crack-crack-crack! And the only answer

is echoes, echoes, echoes.

Only the whirlwind’s long laughter

criss-crossing the snows.

Crack-crack-crack!

Crack-crack-crack!

From street to street with sovereign stride,

a hungry cur behind them…

While bearing a blood-stained banner,

blizzard-invisible,

bullet-untouchable,

tenderly treading through snow-swirls,

hung with threads of snow-pearls,

crowned with snow-flake roses –

who,

who else

but Jesus Christ?

Robert Chandler’s translations from Russian include Vasily Grossman’s Everything Flows and Life and Fate and many works by Andrey Platonov. He has compiled two anthologies for Penguin Classics, of Russian short stories and Russian magic tales; a third anthology – of Russian poetry – will be coming out this November. He is also the author of a “Brief Life” of Alexander Pushkin.

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok (1880-1921) was born in Saint Petersburg; his father was a professor of law in Warsaw, his mother a literary translator, and his maternal grandfather the rector of Saint Petersburg University. His parents separated soon after his birth and he spent much of his childhood at Shakhmatovo, his maternal grandfather’s estate near Moscow. There he discovered the religious philosopher Vladimir Solovyov and the poetry of Tyutchev and Fet, both still surprisingly little known. Shakhmatovo would remain for Blok the image of a lost paradise.

In 1903 Blok married Lyubov Mendeleyeva, the daughter of Dmitry Mendeleyev, the chemist who created the Periodic Table of the elements. It was to Lyubov that he dedicated his poem-cycle, Verses About the Beautiful Lady (1904). For well over a year, however, the marriage remained unconsummated. Eventually, Lyubov seduced him, but this did not resolve his difficulties; he appears to have believed that sex was humiliating to women. He and Lyubov remained together, but their marriage was largely asexual; both had affairs with others.

The idealism of Blok’s first book yielded to a recognition of the tension between this idealism and reality – and the ‘Beautiful Lady’ yielded her place to the more louche figure of the ‘Stranger’.

The greatest of Blok’s later poems are meditations on Russia’s destiny. ‘The Twelve’ (1918), is an ambiguous welcome to the October Revolution. In staccato rhythms and colloquial language, the poem evokes a winter blizzard in revolutionary Petrograd; twelve Red Guards marching through the streets seem like Christ’s Twelve Apostles. Many of Blok’s fellow-writers hated this poem for its apparent acceptance of the Revolution; Bunin, for example, dismissed it as ‘a jumble of cheap verses… completely trashy, clumsy and vulgar beyond measure.’ Bolsheviks, on the other hand, disliked the poem for its mysticism. One of the few positive responses was Leon Trotsky’s: ‘To be sure, Blok is not one of ours, but he reached towards us… “The Twelve” is the most significant work of our epoch.’

Blok’s biographer Avril Pyman writes, ‘Blok had spent two months prior to his composition of ‘The Twelve’ walking the streets, and the snatches of conversation written into the poem, the almost cinematic, angled glimpses of hurrying figures slipping and sliding over or behind drifts or standing rooted in indecision as the storm rages around them work as in a brilliantly cut documentary film. […] The different rhythms are unified by the wind, stilled only in the last line.’

During his last five years Blok’s chronic depression deepened. For nearly two years between 1916 and 1918 he wrote nothing. After writing ‘The Twelve’ and one other poem in less than two days and noting, ‘A great roaring sound within and around me. Today, I am a genius,’ he fell back into a still longer silence. To the poet Korney Chukovsky he said, ‘All sounds have stopped. Can’t you hear that there are no longer any sounds?’ During the last three years of his life, Blok wrote only one poem, ‘To Pushkin House’ – an invocation of Pushkin’s joy and ‘secret freedom’ – and several prose articles.

Boris Pasternak tells how, towards the end of Blok’s life, Mayakovsky once suggested they go together to defend Blok at a public event where he was likely to be criticized: ‘By the time we got (there). . . Blok had been told a pile of monstrous things and they had not been ashamed to tell him that he had outlived his time and was inwardly dead – a fact with which he calmly agreed.’

In spring 1921 Blok did indeed fall ill, with asthma and heart problems. His doctors wanted him to receive medical treatment abroad, but he was not allowed to leave the country, in spite of Maxim Gorky’s pleas. Blok died on 7 August 1921.

Blok was the best known figure of his time and is still considered one of Russia’s greatest poets, but there have always been doubting voices. D.S. Mirsky writes, ‘But great though he is, he is also most certainly an unhealthy and morbid poet, the greatest and most typical of a generation whose best sons were stricken with despair and incapable of overcoming their pessimism except by losing themselves in a dangerous and ambiguous mysticism or by intoxicating themselves in a passionate whirlwind.’ Only four years earlier, Mirsky had said that if he had to choose between ‘The Twelve’ and all the rest of Russian literature put together, he would hesitate.’ Few poems have had such power to polarize opinion – let alone the opinions of a single person.

Akhmatova referred to Blok as ‘the tragic tenor of the epoch.’ She also wrote, ‘I don’t really need Blok any more, but when you begin to read it, Blok’s poetry is as compelling as music.’ He himself, in ‘To the Muse’, had once written:

And I knew a destructive pleasure

in trampling what’s sacred and good,

a delirium exceeding all measure –

this absinthe that poisons my blood!

.

Back to poet list…

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Feb 27 2014

London Grip New Poetry Spring 2014

*

This issue of London Grip New Poetry features poems by:

*Teoti Jardine *Carol DeVaughn *Michael Lee Johnson *John Snelling *Robert Nisbet

*Louise Warren *Jennie Christian *Ricky Garni *Kate Foley

*Christopher Mulrooney *Ian C Smith *Shanta Acharya

*Jennifer Johnson *Ruth Bidgood *Robert Chandler

Copyright of all poems remains with the contributors

A printer-friendly version of London Grip New Poetry can be obtained at LG new poetry Spring 2014

Please send submissions for the future issues to poetry@londongrip.co.uk, enclosing no more than three poems and including a brief, 2-3 line, biography

Editor’s Introduction

The spring edition of London Grip New Poetry begins with a meditative – almost mystic – response to the present crisis in Syria and ends with some fine atmospheric translations of poems from early twentieth-century Russia. En route from one to the other, the reader will encounter poems which touch on the Cold War period with its protest songs and its actual protests. It is good to be reminded that poetry is able to deal with wider issues of history and politics as well as with currently-felt experiences and personal recollections. Of course, private memories, both poignant and bizarre, do also figure among the poems which follow, as do out-and-out works of fantasy. In compiling this varied selection it has been a pleasure to receive submissions from (and sometimes to converse with) poets in many parts of the world. Some of our authors are making repeat appearances while others are first-timers. It has been particularly encouraging to receive work from poets who are previously unpublished – when one of these new voices displays a strong individuality. It is to be hoped that readers will enjoy reading this issue as much as the editor enjoyed seeing it take shape.

*

Shortly before this introduction was written we heard the sad news of the death of Sebastian Barker. He will be widely remembered for his fine, reflective poetry, which often made skilful use of rhyme and form, and for his perceptive and encouraging editorship of The London Magazine. The many tributes paid since his death show that he will also be much missed as a warm and generous human being. (Helen Donlon’s thoughtful article about Sebastian Barker’s childhood can be found at https://londongrip.co.uk/2012/02/an-arcadian-literary-childhood-in-tilty/)

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs

http://mikeb-b.blogspot.com/

Back to poet list… Forward to first poem

***

Teoti Jardine: Syria

The wind remembers the promise of the touching. The resounding response, YES. Waves chanted upon the shore, remember. We had pleaded, allow us to become, we were asked, will you remember, yes we cried, we will remember. Permission given, the BE sounded. The place, perfectly prepared. All the names, mirrored within us. How easily we succumbed to ownership. Tasting beauty, our longings aroused, and found release in lordship-ness. We had chorused YES, left it unrequited. That YES, still resides, these times our readying. Cranes and geese cast their shadows on the desert, where each grain of sand, knows it is not other..

Teoti Jardine was born in Queenstown New Zealand, of Maori, Irish and Scottish descent. His tribal affiliations are Waitaha, Kati Mamoe, and Kai Tahu. He completed the Hagley Writers Course in 2011, and has poetry published in The Christchurch Press, The Burwood Hospital News Letter, London Grip, Te Panui Runaka, Te Karaka, and Ora Nui. His short stories have been published in Flash Frontier’s International Issues, 2013

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Carol DeVaughn: Rain

If rain could speak it would tell us the history of its downpours - the stories of lives that stream into ours how its water rises in clouds and mists carrying a memory of the dead and the living like lovers sleeping in meadow grass; how it falls on unknowing houses, makes harmonies along roofs and walls, wakes somnambulant air from its spell, sweeps away nightmares, strives to make spheres on windowpanes. It remembers the meadow grass and the felicity of molecules..

Carol DeVaughn, American-born, has been living and working in London since 1970. Retired from full-time teaching, she is now preparing her first full collection. Her poems have appeared in magazines and anthologies and she has won several prizes, including a Bridport in 2012.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Michael Lee Johnson: Rainbow in April

April again, the wind falls in love with itself skipping across asphalt and concrete bare with the breaking weather A rainbow

is half arched,

broken off deep

into the aorta

of the gray sky.

It hangs

as if from

rubber bands

its mixed colors

drawn from God’s

inkwell,

and brushed

by the fingertips

of Michelangelo.

April again,

the wind steps high.

A rainbow

is half arched,

broken off deep

into the aorta

of the gray sky.

It hangs

as if from

rubber bands

its mixed colors

drawn from God’s

inkwell,

and brushed

by the fingertips

of Michelangelo.

April again,

the wind steps high..

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Michael Lee Johnson: Red Rocking Chair

A red rocking chair abandoned in a field

of freshly cut clover,

rocks back and forth-

squeaks each time

the wind pushes

at its back,

then,

retreats.

abandoned in a field

of freshly cut clover,

rocks back and forth-

squeaks each time

the wind pushes

at its back,

then,

retreats..

.

.

Michael Lee Johnson lived ten years in Canada during the Vietnam era. Today he is a poet, freelance writer, photographer who experiments with poetography (blending poetry with photography), and small business owner in Itasca, Illinois. He has been published in more than 750 small press magazines in 26 countries. He edits 7 poetry sites and is the author of The Lost American: From Exile to Freedom, several chapbooks of poetry, including From Which Place the Morning Rises and Challenge of Night and Day, and Chicago Poems. He also has over 69 poetry videos on YouTube.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

John Snelling: The Shop

It’s the shop you always passed in childhood; parents hurrying on elsewhere. A window full of promises, the entrance small, but you always knew that inside it went on forever. You never forgot it but never could recall exactly where it was. Once or twice, as an adult, you returned but couldn’t find it. It’s not there anymore. Maybe, it never was..

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

John Snelling: Journey With No Virgil

Young and uneasy amid wrecked buildings, new towers, in war-scarred London. Hearing the talk of bombs. Learning to fear The Bomb. Schooled to appease an angry vengeful God, trinity of Jornado del Muerto. Lost at the beginning of life’s way in a shadowed metal forest. War grew cold. ‘All hope abandon’ said the sign; protest and rebellion our response. We thought our parents stiff misguided fools, that love was all you need, that we could fix a shattered world with slogan and sit-in. We joined, we followed, waved our banners high and we sang in the streets as we marched.Jornado del Muerto: The name of the desert area in which the first atomic bomb test was carried out. The test was codenamed ‘Trinity’. The name of the valley means ‘journey of the dead man’.

.

John Snelling has been writing poetry since the 1960s. In 1976, he won first prize in the City of Westminster Arts Council’s poetry competition. After this, success in competitions eluded him until, in 2013, he gained a Judge’s Special Commendation in The Poetry Box competition for dark and horror poetry.

.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Robert Nisbet: A Period Piece

In Martha’s kitchen, steam and the smell of soap. Hot tea and biscuits. She and Jean plucking the threads of a small town’s week. Now there’s a pair of silly sods. Students. That boy Nesbitt and that Wynne Whatsisname, in the Grey Hart Café, thumping that boy’s guitar. These fancy songs, The Times Are Changing, We Will Overcome, and that Bob Dylan-Thomas. So Lorna asks them, What are you singing, boys? and, sarky-like, What is your message? So that Nesbitt says, We’re singing of brotherhood, Mrs. Davies, and love and peace. The cheeky beggar. So Lorna, quick as a flash, says, Do they have sisters in these brotherhoods? Or will you boys run the world? Joking, like. But that flattened them. The two daft lumps. So, every thread inspected, looked at for size and grain and story’s truth and lingered over in the scent of tea, in the peace of Martha’s kitchen..

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Robert Nisbet: Joan and Alice in the Seafront Café

The café’s plain, looks out upon the dock, the wide blue harbour. Joan and Alice, in mid-morning cups, are reminiscing of the present day. I listen, see the photos passed across. And this is Bernard by the uni library …. (On to his room, his hall of residence) … And this is Bernard’s girl friend … (Subdued frisson and I fancy she’ll be mini-skirted well up-thigh.) The picture spread continues: the lecture halls, the campus and the Summer Ball … He’s done well, your Bernard, hasn’t he? A credit to you, Joanie. He thinks he might do advertising. He’ll go far, that boy, go far. Sleet drizzles on the café’s window, in from the dock and the big bay, out to the wide blue distances where Bernard’s father once trawled heavy waters to the West and North, the Irish Sea, the Hebrides, the storms.Robert Nisbet was for several years an associate lecturer in creative writing at Trinity College, Carmarthen, where he also worked for a while as an adjunct professor for the Central College of Iowa. His short stories appear in Downtrain (Parthian, 2004) and his poems in Merlin’s Lane (Prolebooks, 2011).

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Louise Warren: Alice and the hornet

Insistent as an unloved uncle, drunken, bumping back and forth from his brightly lit doorway, that pouch of poison bulging between his whiskered legs. He makes one last lunge towards her, into the air, you are so young and beautiful he growls, I want to wrap myself in your hair. I want to burrow deeper into those hot dark drifts. She is on her feet now, feeling him, elderly pupa, crawling back to infancy. You are so warm, he croons, my love, just let me..

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Louise Warren: Balconies

One by one we step out into the mild London night, and lean our arms against the white railings. The trees are huge now, engulfing the square like barrage balloons. They creak and sway, billowing their black silks. There is a tension in the air, someone shouts out, something like a plea and our hands loosen for a moment, distracted by the voice, the wind, the strange black silks straining against their ropes. Look at us, just scraps holding onto the edge with our fingertips.Louise Warren won the Cinnamon Press First Collection Prize and her book A Child’s Last Picture Book of the Zoo was published in 2012. She has also been widely published in magazines and anthologies including Agenda, Envoi, Fuselit, Genius Floored Poetry Anthology, The Interpreters House, The New Writer, Orbis, Obsessed with Pipework, Poetry Wales, The Rialto, Seam and Stand. In 2013 her poems were highly commended for both the Ver and Yeovil Poetry Prize.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Jennie Christian: It was labelled ‘Mellow’

An apple is sitting beside me on the sofa. Its rosy glint catches my eye as if it’s trying to tell me something. She told me not to take too much at once, that girl in Amsterdam. So why did I put all of that sachet into our pesto for lunch? And where’s S? He was here 10 seconds ago. The room is the wrong shape. A buzz creeps around the top of my skull, smelling of bacon. My watch says 5.40pm. Some years later, it says 5.45pm. Must get a grip. Eat something? An apple would be nice I’ll get one from the kitchen oh no there’s one right here I’m scared I want my old brain back this one is overflowing endless thoughts chase each other down endless tunnels and there’s no way out no way no Somewhere a dog is barking She has difficulty understanding the dog who speaks poor English Everything is Falling into a Crevice of your Mind the room is now a giant Pumpkin and i am on the Inside trying to rip myself Out phone rings my sister can’t understand what she says please come over, come right now I want to say but words are jumbled spaghetti stuck in neverendingtangle can’t remember wheresentencestarted whatsentence nosense nonsense oh god oh my god help me Go on the balcony, get some air. That will help. Then just glide off into the breeze. Up, up, up... No no no someone will come and take me away must do something anything I take a bite of apple, which laughs crunchily. Its words are perfectly clear. What did I tell you, dopehead?.

Jennie Christian is based in London. Her poems have appeared (or are due to) in poetry journals and magazines including Agenda Poetry (Rilke issue 2007, online supplement), Orbis Quarterly International Literary Journal (#162 Winter 2012-13), SOUTH (issue 48, October 2013) and Obsessed with Pipework (January 2014); also several anthologies

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ricky Garni: Foods That Are Good For Dry Skin

I look at an avocado, split and sundered and I don’t think of a hazel vulva. I think of my banana-colored Volvo, which exploded in the parking lot– it frightened the elderly ladies nearby who were wearing vulvas and already crying. I look at salmon, and I think: where is the lemon and ice? Where is the fine sweater that you once told me to find, salmon hued, and I explained forthwith that I had left it in the truck with a man with a gun named Jedidiah whose manner was vulgar? It was a flatbed truck, filled with ice and lemon, and it was a dream. A dream of Jedidiah’s, or am I dreaming of Jedidiah’s dream? Am I just a dream of Jedidiah? Who knows? I look at a sweet potato, and I think to myself: what is wrong with this world? Why can’t we all just get along? And then I eat a sweet potato..

Ricky Garni is a writer and designer living in North Carolina. He is presently completing a collection of tiny(I mean, these are teensy tiny!) poems entitled What’s That About, dutifully banged out on Faye Hunter’s 1971 Smith Corona typewriter in purple cursive typeset, and dedicated with great affection to her memory.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Kate Foley: Money To Burn

This is what you burn for the dead if you're Chinese. Little packets of gold foil. They curl up, baby dragons, stretching in the flame of their lives, and go out diminuendo, like ash flakes. In the west we have fireworks, which nobody connects with dying: cop-drama bangs. But the sudden rain of sparks, like golden umbrella spokes opened in the sky is fresh as rain itself. As fresh as the pathos of things that don't know they're discarded, the lumpy blue of tightfisted mussel shells now open, the lace's gracile fall from a dead shoe. It's a bit like gold Chinese money poked into the stiff hands of the departed with guilty love. You can't help feeling a stab of pleasure that your heart is live enough to quiver as bank notes curl in the borrowed life of fire..

Kate Foley‘s 5th full collection One Window North was published by Shoestring Press in 2012. She lives, writes and leads workshops between Amsterdam and Suffolk.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Christopher Mulrooney: grotto

you can’t miss the thing at all there’s the street it goes right by and there the town square you pass along and suddenly there’s the place look here you plump you down I say are you mad quite folly-cast took sick blind as any shrieking bat well take out your money here and now when the morning stars sang they emptied their filth into this place now have you seen my will in the matter there is them as wants it shall not have it you and I have a lot of ground to cover is it really as hard as all that come have you squinted or lollygagged instead of using your wits have you tried well then here’s your tea and slop be content go ahead and take a look now it won’t harm you that’s it with you taking a look we’ll have you settled and all this place now very soon a place for everything and everything in its place you do not bargain very well my friend if you do not have me well do you have nothing you know very well what you have and bear it there’s an end laid on you have you know your just deserts do not mistake this for a place of anomaly you know it for what it is a grotto nothing more many more like it every day so do your work be glad and health and fitness attend you labouring what is this a garden where the gardener yes that’s a story for another day what I shall say for this while is have a care remember our first meeting that is all that’s enough and if our journeys end they meet as meet we now and thus complete the peril and the passing time in joy as well as wishing for abandon and reflection there so there a record of these beginnings and endings with the great arc in the middle they teach at school state your purpose and leave your name at the door you’ll have reached the institution in some degreeChristopher Mulrooney has written poems in The Hour of Lead, Black & BLUE, The Cannon’s Mouth, The Seventh Quarry, SAND Journal, Red Branch Journal, The Germ, Auchumpkee Creek Review, Epigraph Magazine, West Wind Review, Pomona Valley Review, TAB: The Journal of Poetry & Poetics, Or, pacific REVIEW, and The Criterion.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ian C Smith: Abattoir Road

These several cherished rooms I call my own in which I read, think, watch the sun emerge through gently rising river fog, the tired dusty chair, the reading glasses that mark my place in second-hand books, form the mute rhythm of serene days. A slew of years all over me, I think of a life far from how I always meant to live. Winter, smells of steel and cooking fat. A boy caught a train without a ticket, thin sleeves rolled to disguise frayed elbows. He would haul dirty laundry in a bag to his sister, already blindly fugitive from meanness into another lifetime trap. Sometimes he took long walks from a rented room, his only option after family meltdown. I interrogate scars on my inked skin, this palimpsest of hungry, dangerous times on lean streets where he dwelt, petrol fumes overlaid by cigarette smoke, grey windows masking violence and sorrow. Though it took so long to journey from that rude room, no fit place for a child, a cathedral choir of ideas now supersedes rage..

Ian C Smith’s work has appeared in Axon:Creative Explorations,The Best Australian Poetry, London Grip, Poetry Salzburg Review, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, The Weekend Australian & Westerly. His latest book is Here Where I Work from Ginninderra Press (Adelaide). He lives in the Gippsland Lakes area of Victoria, Australia.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Shanta Acharya: Ladder of Escape

For Joan Miro

A time for retreat to a world imagined perhaps a river made iridescent by the passage of a swan a time to rise above the incompleteness of life, understand emptiness invisibility, liberation discover magic ladders wander in rapture, peace towards the rainbow guided by phosphorescent tracks of tortoises leaving behind individuality plunging into anonymity a star caressing the breast of happiness casting off cobwebs of prejudices prisons built by us, our past selves… celebrating creation a negation of negations drawing with smoke on air free, magical things connecting earth to sky becoming a tree with ears, eyes a drop of dew falling from the wing of a bird in answer to a prayer prophetic, a ladder of escape..

Shanta Acharya was born and educated in India before studying at Oxford and Harvard. The author of nine books, her latest poetry collection is Dreams That Spell the Light (Arc Publications, UK; 2010). Her poems, articles and reviews have appeared in major publications including Poetry Review, London Magazine, and The Spectator. She is the founder director of Poetry in the House, Lauderdale House in London, where she has been hosting monthly poetry readings since 1996. She was elected to the Board of Trustees of the Poetry Society, UK, in 2011. www.shantaacharya.com

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Jennifer Johnson: Holiday

My heart sinks into the sand they’ve just returned from. Their relentless prattle gets me: hassle, slums, hopeless food, no English. The beach, it seems, was disappointing, full of hawkers and thieves. It looked lovely, they said, when the agent showed them photos in early March. So, they were sold a truly utopian beach, virgin golden sand free from the dark ash of history or politics, without the corrugated iron too many lives rust under or the desperation for notes from the purses of strangers who want photos of paradise and what’s needed for a tan.Jennifer Johnson. has had poems published in several magazines including Acumen, The Frogmore Papers, The Interpreter’s House, Obsessed with Pipework, Orbis, Poetry Salzburg Review, The SHOp, South and Stand and a pamphlet published by Hearing Eye (Footprints on Africa and Beyond, Hearing Eye, 2006).

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ruth Bidgood: Undefined

Probably this photograph is of the woman, though she is so small, so far, she could be incidental. From the road above a grassy slope, she seems to be looking down at him. His lens is turned towards her, but doesn’t zoom in to lessen the distance between them. That may be the subject – distance: the small figure below sombre crags above the long steep drop to the river. No certainty of any interchange; maybe a look? Maybe. Only the lens, making its moment’s précis, has definition. The hinted story has none..

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Ruth Bidgood: Wrong Turn

I should not have been there, shall not be there again, shall not forget. The lane meandered through a thin wood, went on too long, brought conviction only of trespass. Suddenly the trees sat back, lane became drive, pillared bridge led to gravelled forecourt. Long, low, redly creepered in September sun, the house glowed. No sound except a river’s understated calm-weather song. From the bridge, deep shadow. A mill down there, huge wheel motionless, seeming not disused but resting from use, workaday, but in that dimness not without mystery. I realised it was the Wye that flowed as millstream here, queen playing handmaid. Looking back at the house before leaving, unexpectedly I felt kinship between its life and mine, both being contradictory, unclear. It lived on two levels, plunged from sun to shade; was hard in stone, in water, shifting, mutable. It had a kind of certainty, yet endured tremors of hauntedness. This place had been intruded on, and yet had taken me, chance-come questioner, into its unknown story; destined to stay in mine, had made an entry, unwilled, uninvited, welcome..

Ruth Bidgood lives in Mid-Wales.. She has published 13 books of poems, and one prose book about the Abergwesyn area of old North Breconshire, which was her home for many years. She also contributes research articles to county journals In Powys and Carmarthenshire.

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

Robert Chandler: Translations of poems by Alexander Alexandrovich Blok

She came in out of the frost

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok 6 February 1908, tr. Robert Chandler

She came in out of the frost her cheeks glowing, and filled my whole room with the scent of fresh air and perfume and resonant chatter that did away with my last chance of getting anywhere with my work. Straightaway she dropped a hefty art journal onto the floor and at once there was no room any more in my large room. All this was somewhat annoying, if not absurd. Next, she wanted Macbeth read aloud to her. Barely had I reached the earth’s bubbles which never fail to entrance me when I took in that she, no less entranced, was staring out of the window. A large tabby cat was creeping along the edge of the roof towards some amorous pigeons. What angered me most was that it should be pigeons, not she and I, who were necking, and that the days of Paolo and Francesca were long gone..

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

When you stand in my path

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok 6 February, 1908, tr. Robert Chandler

When you stand in my path, so alive, so beautiful, yet so tormented; when you talk only of what is sad, when your thoughts are of death, when you love no one and feel such contempt for your own beauty – am I likely to harm you? No… I’m no lover of violence, and I don’t cheat and am not proud, though I do know many things and have thought too much ever since childhood and am too preoccupied with myself. I am, after all, a composer of poems, someone who calls everything by its name and spirits away the scent from the living flower. For all your talk of what is sad, for all your thoughts of beginnings and endings, I still take the liberty of remembering that you are only fifteen. Which is why I wish you to fall in love with an ordinary man who loves the earth and the sky more than rhymed or unrhymed talk of the earth and the sky. Truly, I will be glad for you, since only someone in love has the right to be called human..

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

from ‘Dances of Death’

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok 10 October 1912, tr. Robert Chandler

Night, lantern, side-street, drug store, a mindless, pallid light. Live on for twenty years or more – it’ll be the same; there’s no way out. Try being reborn – start life anew. All’s still as boring and banal. Lantern, side-street, drug store, a few shivering ripples on a canal..

Back to poet list… Forward to next poem

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

***

from ‘The Twelve’

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok January 1918, tr. Robert Chandler

From street to street with sovereign stride… – Who’s there? Don’t try to hide! But it’s only the wind playing with the red banner ahead. Cold, cold, cold drifts of snow. – Who’s there? No hiding now! But it’s only a starving hound limping along behind. Get lost, you mangy cur – or we’ll tickle you with our bayonets. This is the last of you, old world – soon we’ll smash you to bits. The mongrel wolf is baring his fangs – it’s hard to scare him away. He’s drooping his tail, the bastard waif… – Hey, you there, show your face! Who can be waving our red banner? Wherever I look – it’s dark as pitch! Who is it flitting from corner to corner always out of our reach? – Doesn’t matter, we’ll flush you out. Better give yourself up straightaway! Quick, comrade – you won’t get away when we start to shoot! Crack-crack-crack! And the only answer is echoes, echoes, echoes. Only the whirlwind’s long laughter criss-crossing the snows. Crack-crack-crack! Crack-crack-crack! From street to street with sovereign stride, a hungry cur behind them… While bearing a blood-stained banner, blizzard-invisible, bullet-untouchable, tenderly treading through snow-swirls, hung with threads of snow-pearls, crowned with snow-flake roses – who, who else but Jesus Christ?Robert Chandler’s translations from Russian include Vasily Grossman’s Everything Flows and Life and Fate and many works by Andrey Platonov. He has compiled two anthologies for Penguin Classics, of Russian short stories and Russian magic tales; a third anthology – of Russian poetry – will be coming out this November. He is also the author of a “Brief Life” of Alexander Pushkin.

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok (1880-1921) was born in Saint Petersburg; his father was a professor of law in Warsaw, his mother a literary translator, and his maternal grandfather the rector of Saint Petersburg University. His parents separated soon after his birth and he spent much of his childhood at Shakhmatovo, his maternal grandfather’s estate near Moscow. There he discovered the religious philosopher Vladimir Solovyov and the poetry of Tyutchev and Fet, both still surprisingly little known. Shakhmatovo would remain for Blok the image of a lost paradise.

In 1903 Blok married Lyubov Mendeleyeva, the daughter of Dmitry Mendeleyev, the chemist who created the Periodic Table of the elements. It was to Lyubov that he dedicated his poem-cycle, Verses About the Beautiful Lady (1904). For well over a year, however, the marriage remained unconsummated. Eventually, Lyubov seduced him, but this did not resolve his difficulties; he appears to have believed that sex was humiliating to women. He and Lyubov remained together, but their marriage was largely asexual; both had affairs with others.

The idealism of Blok’s first book yielded to a recognition of the tension between this idealism and reality – and the ‘Beautiful Lady’ yielded her place to the more louche figure of the ‘Stranger’.

The greatest of Blok’s later poems are meditations on Russia’s destiny. ‘The Twelve’ (1918), is an ambiguous welcome to the October Revolution. In staccato rhythms and colloquial language, the poem evokes a winter blizzard in revolutionary Petrograd; twelve Red Guards marching through the streets seem like Christ’s Twelve Apostles. Many of Blok’s fellow-writers hated this poem for its apparent acceptance of the Revolution; Bunin, for example, dismissed it as ‘a jumble of cheap verses… completely trashy, clumsy and vulgar beyond measure.’ Bolsheviks, on the other hand, disliked the poem for its mysticism. One of the few positive responses was Leon Trotsky’s: ‘To be sure, Blok is not one of ours, but he reached towards us… “The Twelve” is the most significant work of our epoch.’

Blok’s biographer Avril Pyman writes, ‘Blok had spent two months prior to his composition of ‘The Twelve’ walking the streets, and the snatches of conversation written into the poem, the almost cinematic, angled glimpses of hurrying figures slipping and sliding over or behind drifts or standing rooted in indecision as the storm rages around them work as in a brilliantly cut documentary film. […] The different rhythms are unified by the wind, stilled only in the last line.’

During his last five years Blok’s chronic depression deepened. For nearly two years between 1916 and 1918 he wrote nothing. After writing ‘The Twelve’ and one other poem in less than two days and noting, ‘A great roaring sound within and around me. Today, I am a genius,’ he fell back into a still longer silence. To the poet Korney Chukovsky he said, ‘All sounds have stopped. Can’t you hear that there are no longer any sounds?’ During the last three years of his life, Blok wrote only one poem, ‘To Pushkin House’ – an invocation of Pushkin’s joy and ‘secret freedom’ – and several prose articles.

Boris Pasternak tells how, towards the end of Blok’s life, Mayakovsky once suggested they go together to defend Blok at a public event where he was likely to be criticized: ‘By the time we got (there). . . Blok had been told a pile of monstrous things and they had not been ashamed to tell him that he had outlived his time and was inwardly dead – a fact with which he calmly agreed.’

In spring 1921 Blok did indeed fall ill, with asthma and heart problems. His doctors wanted him to receive medical treatment abroad, but he was not allowed to leave the country, in spite of Maxim Gorky’s pleas. Blok died on 7 August 1921.

Blok was the best known figure of his time and is still considered one of Russia’s greatest poets, but there have always been doubting voices. D.S. Mirsky writes, ‘But great though he is, he is also most certainly an unhealthy and morbid poet, the greatest and most typical of a generation whose best sons were stricken with despair and incapable of overcoming their pessimism except by losing themselves in a dangerous and ambiguous mysticism or by intoxicating themselves in a passionate whirlwind.’ Only four years earlier, Mirsky had said that if he had to choose between ‘The Twelve’ and all the rest of Russian literature put together, he would hesitate.’ Few poems have had such power to polarize opinion – let alone the opinions of a single person.

Akhmatova referred to Blok as ‘the tragic tenor of the epoch.’ She also wrote, ‘I don’t really need Blok any more, but when you begin to read it, Blok’s poetry is as compelling as music.’ He himself, in ‘To the Muse’, had once written:

And I knew a destructive pleasure

in trampling what’s sacred and good,

a delirium exceeding all measure –

this absinthe that poisons my blood!

.

Back to poet list…

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.