Poetry review – girls etc: Emma Lee admires Rhian Elizabeth’s ability to relate personal experience in a voice that is both natural and poetic.

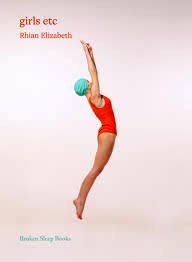

girls etc

Rhian Elizabeth

Broken Sleep Books

ISBN 9781915760623

58pp £9.99

girls etc

Rhian Elizabeth

Broken Sleep Books

ISBN 9781915760623

58pp £9.99

Rhian Elizabeth’s girls etc is a collection of lyrical poems that explore motherhood as a teenager and also hint at intimate partner violence in a lesbian relationship – although the poems are more concerned with the aftermath and getting back on track while being honest about hard truths. The first poem, “september 30, 2005” starts with two images – a newborn testing her lungs for the first time and the mother screaming through labour –and it ends, years later with a single observation

you still have the lungs of a lion,

and we are both still screaming.

The suggestion here is that the now teenaged daughter is still healthy, despite being born to a teenage mother, and that both mother and daughter are communicating, despite ups and downs. It’s when a teenager stops speaking to her only parent that one worries they are in trouble.

In “the daughters of eden” the view switches from mother and daughter to mother and partner, as the poem winders what might have happened if there had been no Adam but two Eves instead,

would either eve have snatched

the forbidden apple from the tree,

given in to temptation?

i would have been too preoccupied with her nakedness

to even notice the serpent.

It’s a refreshing twist on the ‘it must have been the woman’s fault’ narrative the story usually attracts. The last line implies a turning away from heterosexual relationships in favour of a relationship with another woman. Perhaps if Adam had succeeding in being sufficiently attentive to Eve, she wouldn’t have paid attention to the serpent either. However, the relationship turns sour. “girls don’t hurt girls” starts with a consideration of the Bette Davies/Joan Crawford feud where the latter observed,

bette davis lacked the absence of any real

beauty and girls will be girls when

there are boys involved and egos at stake

but this wasn't like that she hurt me

why didn't you tell the police?

i almost did a few times

The Hollywood stars’ feud is almost explained away by a competition over men, the ‘girls will be girls’ a take on the more usual ‘boys will be boys’ argument for tolerating bad behaviour. The narrative is broken by pauses where the narrator is forced to look at her own relationship. The gaps on the page suggest hesitancy. It’s difficult to open up about abuse when the abuser may have urged secrecy. There’s a shame that keeps victims quiet as they fear they will be blamed or suspect it’s their fault. Calling the police isn’t easy in a heterosexual relationship: there’s a fear of not being believed, not knowing what to expect and worry about being blamed or meeting the suggestion that the victim’s behaviour somehow provoked the perpetrator. For a same-sex relationship there are additional concerns: women aren’t generally seen as being perpetrators; and the victim may be blamed for not leaving when there isn’t the usual explanation of fear and the perpetrator having the muscular advantages of a male. At this stage it’s not clear what ‘she hurt me’ means, whether the abuse was psychological, emotional and/or physical. That comes later in “monster” where the monster drops sweets into children’s buckets at Hallowe’en, ‘three days after she broke my nose’ and the children go on to

the neighbour's house, pounding their letterbox,

blissfully unaware that the real monster

was this side of the door.

The narrative switches back to the mother and daughter relationship, with “taylor. fucking. swift”, referring to the hugely popular singer. Here the mother makes the mistake of asking if both she and the singer were drowning, which one would the daughter save?

me or taylor (she could only choose one of us), and i knew

by the awkward silence that followed that it would be me left sinking,

mouth open in a silent screams, while taylor is pulled from the water,

caramel hair falling in perfect, wet curls like an all-american mermaid,

ready to write her next song about heartbreak.

It’s a mistake to ask because mothers are always there, particularly when they are a lone parent. A favourite singer, however, could have just recorded her last album. It’s akin to asking a parent which is their favourite child. You’re not supposed to ask – for good reason.

“if we could just go back i’d push you higher”, returns to a memory. The narrator was sixteen-years-old when she had her baby daughter. Now the daughter is a toddler, big enough to go on a roundabout,

this poem is a memory

19 years old and playing at being a mother

the way you played with your dolls

you deserved so much better, so much better

and now it spins and it spins and it spins

guilt is a roundabout

that won't ever let you get off.

Most loving parents go through patches of guilt at not being good enough. Yet good enough is all children need, since they have to navigate a far from ideal world, a navigation made easier by knowing you have at least one loving parent in support.

Rhian Elizabeth brings a sense of vulnerability and honesty to these poems. The narrator is a poet who admits mistakes, meets people with a warmth and welcome, and is open to experience which brings wisdom. The girls are OK. The poems’ tone of a chat with a good friend feels casual but is underlined by a sense of rhythm, particularly of natural speech, to achieve that effect. They are rather like a roundabout that works smoothly and doesn’t call attention to the mechanics underneath the ride.

Apr 24 2024

London Grip Poetry Review – Rhian Elizabeth

Poetry review – girls etc: Emma Lee admires Rhian Elizabeth’s ability to relate personal experience in a voice that is both natural and poetic.

Rhian Elizabeth’s girls etc is a collection of lyrical poems that explore motherhood as a teenager and also hint at intimate partner violence in a lesbian relationship – although the poems are more concerned with the aftermath and getting back on track while being honest about hard truths. The first poem, “september 30, 2005” starts with two images – a newborn testing her lungs for the first time and the mother screaming through labour –and it ends, years later with a single observation

The suggestion here is that the now teenaged daughter is still healthy, despite being born to a teenage mother, and that both mother and daughter are communicating, despite ups and downs. It’s when a teenager stops speaking to her only parent that one worries they are in trouble.

In “the daughters of eden” the view switches from mother and daughter to mother and partner, as the poem winders what might have happened if there had been no Adam but two Eves instead,

It’s a refreshing twist on the ‘it must have been the woman’s fault’ narrative the story usually attracts. The last line implies a turning away from heterosexual relationships in favour of a relationship with another woman. Perhaps if Adam had succeeding in being sufficiently attentive to Eve, she wouldn’t have paid attention to the serpent either. However, the relationship turns sour. “girls don’t hurt girls” starts with a consideration of the Bette Davies/Joan Crawford feud where the latter observed,

The Hollywood stars’ feud is almost explained away by a competition over men, the ‘girls will be girls’ a take on the more usual ‘boys will be boys’ argument for tolerating bad behaviour. The narrative is broken by pauses where the narrator is forced to look at her own relationship. The gaps on the page suggest hesitancy. It’s difficult to open up about abuse when the abuser may have urged secrecy. There’s a shame that keeps victims quiet as they fear they will be blamed or suspect it’s their fault. Calling the police isn’t easy in a heterosexual relationship: there’s a fear of not being believed, not knowing what to expect and worry about being blamed or meeting the suggestion that the victim’s behaviour somehow provoked the perpetrator. For a same-sex relationship there are additional concerns: women aren’t generally seen as being perpetrators; and the victim may be blamed for not leaving when there isn’t the usual explanation of fear and the perpetrator having the muscular advantages of a male. At this stage it’s not clear what ‘she hurt me’ means, whether the abuse was psychological, emotional and/or physical. That comes later in “monster” where the monster drops sweets into children’s buckets at Hallowe’en, ‘three days after she broke my nose’ and the children go on to

The narrative switches back to the mother and daughter relationship, with “taylor. fucking. swift”, referring to the hugely popular singer. Here the mother makes the mistake of asking if both she and the singer were drowning, which one would the daughter save?

It’s a mistake to ask because mothers are always there, particularly when they are a lone parent. A favourite singer, however, could have just recorded her last album. It’s akin to asking a parent which is their favourite child. You’re not supposed to ask – for good reason.

“if we could just go back i’d push you higher”, returns to a memory. The narrator was sixteen-years-old when she had her baby daughter. Now the daughter is a toddler, big enough to go on a roundabout,

this poem is a memory 19 years old and playing at being a mother the way you played with your dolls you deserved so much better, so much better and now it spins and it spins and it spins guilt is a roundabout that won't ever let you get off.Most loving parents go through patches of guilt at not being good enough. Yet good enough is all children need, since they have to navigate a far from ideal world, a navigation made easier by knowing you have at least one loving parent in support.

Rhian Elizabeth brings a sense of vulnerability and honesty to these poems. The narrator is a poet who admits mistakes, meets people with a warmth and welcome, and is open to experience which brings wisdom. The girls are OK. The poems’ tone of a chat with a good friend feels casual but is underlined by a sense of rhythm, particularly of natural speech, to achieve that effect. They are rather like a roundabout that works smoothly and doesn’t call attention to the mechanics underneath the ride.