Poetry review – THE TRAPEZE OF YOUR FLESH: Thomas Ovans is impressed by the extensive knowledge behind Charles Rammelkamp’s poetic history of Striptease and Burlesque

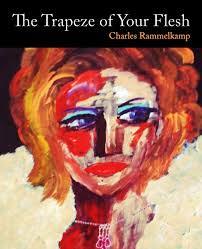

The Trapeze of your Flesh

Charles Rammelkamp

Blaze VOX Books

ISBN: 978-1-60964-465-9

174pp $20

The Trapeze of your Flesh

Charles Rammelkamp

Blaze VOX Books

ISBN: 978-1-60964-465-9

174pp $20

Charles Rammelkamp’s name will be familiar to London Grip readers as a zealous and prolific reviewer of poetry published in the USA. His own poetic gifts may be less well-known in the UK but we are here reversing the usual order of things and putting his latest collection through the London Grip review process.

The Trapeze of your Flesh is essentially a poetic history of what Americans often call Burlesque but which essentially is the art of stripping. Rammelkamp must have done a huge amount of research to compose over 150 pages of narrative poems about notable performers, mainly from the USA but also from Britain and Europe. There are some positive tales of women who survive and flourish in spite of abuse and exploitation in their early lives; but it has to be admitted that there are as many – if not more – stories that end in sadness. Rammelkamp may be keen to find the upbeat or amusing elements in a story but he does not shrink from telling unhappy truths.

At one level this book is a remarkable assemblage of rather obscure facts. Who knew, for instance, that there was a strippers’ protest in Baltimore when adult entertainment venues did not reopen at the same time as other theatres at the end of the Covid lockdown? We learn about that event in the first poem “Tina James Raises Her Voice”. And who knew that there was a “British invasion” almost a hundred years before the Beatles took America by storm? Lucy Thompson and the British Blondes charmed America for six years during the 1860s; but, unlike John Lennon, ‘never claimed / to be more popular than Jesus.’ Their prolonged tour was not exactly trouble-free (as we learn in the second poem in the collection) but nevertheless ‘It was exciting being a star! / All you need? Love.’

Following the example set by the Brits, the first home-grown American stripper Mabel Santley emerged soon afterwards – although the height of daring at this point in theatrical history was lifting ‘my skirt above my knees. Shocking!’

There is something of a fast-forward after this and only a few pages later we have reached 1952 and the appearance of a Burlesque artist as a contestant on What’s My Line. She almost outwits the panel. Thereafter, in poem after poem, Rammelkamp presents us with a huge amount of information about striptease artistes of the last 75 or so years. He quotes their vital statistics – particularly chest measurements as in “The Great 48” – and draws no veil over links with organised crime or with high-ranking politicians including Presidents. One performer, April March, was called the First Lady of Burlesque ‘because I looked so much like Jackie Kennedy’ which might conceivably have led to one or two awkward situations!

As well as dealing with performers’ back-stories Rammelkamp gives us glimpses of how they appeared on stage. He ventriloquises Candy Barr (so-called ‘because I liked Snickers so much’) describing herself

My get-up was a cowgirl costume,

cowboy hat, pasties and scant panties,

a couple of pearl-handled six-shooters

in a hip holster, cowboy boots.

I was hot.

Elsewhere he reports of Betty Rowland that she was

a graceful redhead,

famous for her “German roll,”

an undulating bump and grind;

From time to time Rammelkamp brings himself into the narrative describing his own responses to the lives of his most famous heroines.

To the tune of “Eleanor Rigby,”

my mind idly sang to itself:

Josephine Baker, picks up the rice in a church...

The pandemic still raged, November, 2021,

when I read in the newspaper about

the French honoring the famous dancer

He is particularly diverted by the fact that Baker’s ‘“Danse Sauvage,” wearing a skirt with a string / of artificial bananas, made her an instant star.’ And he completes his borrowing from Eleanor Rigby with

Josephine Baker danced on the stage

wearing a skirt and not very much more…

So there she was, a casket in the Panthéon.

Buried along with her name.

Everyone came…

Of course Rammelkamp is not the first (or only) poet to be interested in dancing girls. The collection’s title comes from a poem by Hart Crane. And in “One Night on Second Avenue” Mae Dix is portrayed as hoping that Crane had her in mind when he wrote his phrase Outspoken buttocks in pink beads. It might not be expected however that dancing girls would vice versa be interested in literary matters. So who knew that the famous Gypsy Rose Lee wrote a successful mystery novel called The G-String Murders? Or who knew that the (admittedly less well-known) Vicki “The Back” Dougan claimed as her biggest achievement

I once wrote a poem to Bill Clinton

in his support during the Lewinsky scandal.

The president wrote back, thanking me!

In a book outlining the lives of around a hundred artistes all in the same line of work it is inevitable that there are some repetitions among their experiences. But there are some real surprises too:

My signature act? “The Exploding Couch”:

I’d stretch out on a couch on stage,

then smoke drifted out from between my legs,

like I was getting really worked up,

burning with lust, and then streamers like flames

started blowing, as if the couch had caught fire.

[“The Hottest Blaze in Baltimore”]

Or how about

One dance I called “Half and Half,” half my body

dressed as a groom, the other a bride,

each side undressing the other,

[“Venom”]

In later sections of the book more attention is given to European equivalents of burlesque and we get some language lessons. For instance ‘Cooch comes from the German word kuchen, /meaning pie or cake; /refers to a woman’s vagina’. Or ‘Hochequeue is a French word meaning “to shake a tail” – /“hoochie coochie” comes from that.’ Or ‘The word “burlesque” comes from burlesco, / derived from the Italian burla – / a joke, ridicule, mockery.’

London Grip readers may wonder if any of the poems feature British glamour girls. There are indeed a few. “The Most Photographed Nude in America” is about June Wilkinson who ‘grew up in Eastbourne/ … / where they hold that Wimbledon warm-up tournament’. Rammelkamp can remember ‘drooling over her pictures.’ But much more famous – because she stayed in the UK and became quite a serious actress – is “The Siren of Swindon” Diana Dors. There is now a bronze statue of Diana in her home town and Rammelkamp imagines an aging resident visiting it and saying ‘I still stagger over some Sundays with my walking frame, / just to remember what it was like to be young.’

That rather sentimental note of nostalgia runs through quite a few of the poems. But with a nice sense of symmetry the collection ends as it began on the harder-edged theme of industrial action. “Strippers Unite” celebrates unionisation and strike action in several theatres and clubs over demands for basic employment rights and protections. ‘If Starbucks and Apple can do it, / so can strippers!’ is a suitably boisterous cry with which to finish.

This diverting book is essentially a collection of poem-anecdotes. The content is so much larger-than-life that the poetry doesn’t need to draw attention to itself but rather does the important job of shaping and even calming the crazier episodes. In most cases the poems tell individual stories (although a few characters do occur more than once) so there is little in the way of narrative development; but this makes the book an ideal one for dipping into at random to be pleasurably amused, sometimes moved and occasionally shocked by the goings-on so graphically described.

Apr 21 2024

London Grip Poetry Review – Charles Rammelkamp

Poetry review – THE TRAPEZE OF YOUR FLESH: Thomas Ovans is impressed by the extensive knowledge behind Charles Rammelkamp’s poetic history of Striptease and Burlesque

Charles Rammelkamp’s name will be familiar to London Grip readers as a zealous and prolific reviewer of poetry published in the USA. His own poetic gifts may be less well-known in the UK but we are here reversing the usual order of things and putting his latest collection through the London Grip review process.

The Trapeze of your Flesh is essentially a poetic history of what Americans often call Burlesque but which essentially is the art of stripping. Rammelkamp must have done a huge amount of research to compose over 150 pages of narrative poems about notable performers, mainly from the USA but also from Britain and Europe. There are some positive tales of women who survive and flourish in spite of abuse and exploitation in their early lives; but it has to be admitted that there are as many – if not more – stories that end in sadness. Rammelkamp may be keen to find the upbeat or amusing elements in a story but he does not shrink from telling unhappy truths.

At one level this book is a remarkable assemblage of rather obscure facts. Who knew, for instance, that there was a strippers’ protest in Baltimore when adult entertainment venues did not reopen at the same time as other theatres at the end of the Covid lockdown? We learn about that event in the first poem “Tina James Raises Her Voice”. And who knew that there was a “British invasion” almost a hundred years before the Beatles took America by storm? Lucy Thompson and the British Blondes charmed America for six years during the 1860s; but, unlike John Lennon, ‘never claimed / to be more popular than Jesus.’ Their prolonged tour was not exactly trouble-free (as we learn in the second poem in the collection) but nevertheless ‘It was exciting being a star! / All you need? Love.’

Following the example set by the Brits, the first home-grown American stripper Mabel Santley emerged soon afterwards – although the height of daring at this point in theatrical history was lifting ‘my skirt above my knees. Shocking!’

There is something of a fast-forward after this and only a few pages later we have reached 1952 and the appearance of a Burlesque artist as a contestant on What’s My Line. She almost outwits the panel. Thereafter, in poem after poem, Rammelkamp presents us with a huge amount of information about striptease artistes of the last 75 or so years. He quotes their vital statistics – particularly chest measurements as in “The Great 48” – and draws no veil over links with organised crime or with high-ranking politicians including Presidents. One performer, April March, was called the First Lady of Burlesque ‘because I looked so much like Jackie Kennedy’ which might conceivably have led to one or two awkward situations!

As well as dealing with performers’ back-stories Rammelkamp gives us glimpses of how they appeared on stage. He ventriloquises Candy Barr (so-called ‘because I liked Snickers so much’) describing herself

Elsewhere he reports of Betty Rowland that she was

From time to time Rammelkamp brings himself into the narrative describing his own responses to the lives of his most famous heroines.

He is particularly diverted by the fact that Baker’s ‘“Danse Sauvage,” wearing a skirt with a string / of artificial bananas, made her an instant star.’ And he completes his borrowing from Eleanor Rigby with

Of course Rammelkamp is not the first (or only) poet to be interested in dancing girls. The collection’s title comes from a poem by Hart Crane. And in “One Night on Second Avenue” Mae Dix is portrayed as hoping that Crane had her in mind when he wrote his phrase Outspoken buttocks in pink beads. It might not be expected however that dancing girls would vice versa be interested in literary matters. So who knew that the famous Gypsy Rose Lee wrote a successful mystery novel called The G-String Murders? Or who knew that the (admittedly less well-known) Vicki “The Back” Dougan claimed as her biggest achievement

In a book outlining the lives of around a hundred artistes all in the same line of work it is inevitable that there are some repetitions among their experiences. But there are some real surprises too:

My signature act? “The Exploding Couch”: I’d stretch out on a couch on stage, then smoke drifted out from between my legs, like I was getting really worked up, burning with lust, and then streamers like flames started blowing, as if the couch had caught fire. [“The Hottest Blaze in Baltimore”]Or how about

One dance I called “Half and Half,” half my body dressed as a groom, the other a bride, each side undressing the other, [“Venom”]In later sections of the book more attention is given to European equivalents of burlesque and we get some language lessons. For instance ‘Cooch comes from the German word kuchen, /meaning pie or cake; /refers to a woman’s vagina’. Or ‘Hochequeue is a French word meaning “to shake a tail” – /“hoochie coochie” comes from that.’ Or ‘The word “burlesque” comes from burlesco, / derived from the Italian burla – / a joke, ridicule, mockery.’

London Grip readers may wonder if any of the poems feature British glamour girls. There are indeed a few. “The Most Photographed Nude in America” is about June Wilkinson who ‘grew up in Eastbourne/ … / where they hold that Wimbledon warm-up tournament’. Rammelkamp can remember ‘drooling over her pictures.’ But much more famous – because she stayed in the UK and became quite a serious actress – is “The Siren of Swindon” Diana Dors. There is now a bronze statue of Diana in her home town and Rammelkamp imagines an aging resident visiting it and saying ‘I still stagger over some Sundays with my walking frame, / just to remember what it was like to be young.’

That rather sentimental note of nostalgia runs through quite a few of the poems. But with a nice sense of symmetry the collection ends as it began on the harder-edged theme of industrial action. “Strippers Unite” celebrates unionisation and strike action in several theatres and clubs over demands for basic employment rights and protections. ‘If Starbucks and Apple can do it, / so can strippers!’ is a suitably boisterous cry with which to finish.

This diverting book is essentially a collection of poem-anecdotes. The content is so much larger-than-life that the poetry doesn’t need to draw attention to itself but rather does the important job of shaping and even calming the crazier episodes. In most cases the poems tell individual stories (although a few characters do occur more than once) so there is little in the way of narrative development; but this makes the book an ideal one for dipping into at random to be pleasurably amused, sometimes moved and occasionally shocked by the goings-on so graphically described.