Joan Michelson picks her way through a few flower poems by Peter Phillips

[We can talk. ‘The Garden of Live Flowers’, (Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll, 1871)]

At the Poetry Book Fair in September 2016 I found a Hearing Eye card pamphlet containing four of Peter Phillips’ Flower Poems (from his on-going collection, Saying It With Flowers) illustrated with linocuts by Emily Johns. Phillips also has a poem entitled ‘A Bunch of Flowers’ in Acumen 86 (September 2016).

At the Poetry Book Fair in September 2016 I found a Hearing Eye card pamphlet containing four of Peter Phillips’ Flower Poems (from his on-going collection, Saying It With Flowers) illustrated with linocuts by Emily Johns. Phillips also has a poem entitled ‘A Bunch of Flowers’ in Acumen 86 (September 2016).

Reading these poems against the backdrop of Lewis Carroll and of the Pulitzer Prize 1993 collection, The Wild Iris by the American poet Louise Gluck, gives us a triple-take on the flower as voice for the human. Moreover, in their flower clusters, both Phillips and Gluck have ‘Snowdrop’ speakers. Without wanting to venture any distance into the tricky territory of Gluck’s metaphysics, ethics, and use of imagery, I found it helpful to approach his poem ‘Snowdrops’ from a look at hers.

Gluck’s ‘Snowdrops’ poem opens with despair, while Phillips has the flowers looking sad. Her snowdrop does not expect to survive because earth is suppressing it. Phillips’ snowdrops endure despite whole swathes being wiped out during the desecration of the sacred places that attracted them. After lying beneath wasted ground – some of them for many years – the small white bell flowers push up into the light. Gluck’s snowdrop ‘opens again’. Phillips’ snowdrops live on and his poem continues beyond renewal. Here the two poet-voices differ in ways that invite a separate essay. Gluck’s poem, like many in The Wild Iris, repositions us in the natural world. Phillips picks up the theme he has introduced earlier, extending the consequences of political upheaval, represented by the sacking and plundering of the monasteries of Walsingham and Framlingham. The snowdrops, though innocent, are part of it. They fall under the feet of the horsemen, under the bodies of the dead and lie in earth soaked with blood. Even in this earth, they regenerate, but this is not the only point made. They are victims because they are there and also they are witness-survivors, or the future generations of the survivors of the massacre. They live with their own trauma and say little about it. The relevance to our time hardly need be stated.

The two ‘Snowdrops’ poems end as follows:

crying yes risk joy

in the raw wind of the new world.

[Gluck]

They hadn’t come for us but it was a bloodbath,

we were part of it. No, talking doesn’t help.

[Phillips]

Phillips’ poem makes an imaginative connection with flowers; its tendrils reach out, the touch consistently light and minimal, into history. Each of the poems in the Hearing Eye pamphlet takes the name of a flower for its title: besides ‘Snowdrops’ we find ‘Ukraine Sunflower’. ‘Knotweed’ and ‘Tulips’.

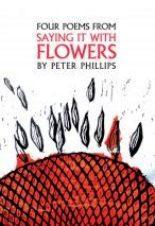

The tulips are black and the march of their black boots is the touchstone image recreated by Emily Johns to introduce the poems. The pamphlet opens to a front-page spread of black tulip figures in march formation. In her VW leaf-leg design, they call up the emblem of the Volkswagen Beetle, Hitler’s car ‘for the people’. A bright translucent blood-red smear runs across the collective lower body as if held in place by a row of invisible hands, and in this we might see a Party banner. The material, like a fine-weave cotton or muslin-silk, from which banners are made, thins out and falls away as it trails towards the back. Like a political banner which carries a slogan, a message is printed on it. FLOWERS stands out in large capital letters, surrounded by the pamphlet title and author’s name. The banner could represent the Communist one, with hammer and sickle missing, or a National Socialist one with swastika missing, or the unadorned sign of the 18th century French Revolutionaries.

Emily John’s linocut illustration is as powerful and expansive as the texts that follow. From ‘Snowdrops’ to ‘Tulips’, interrupted by the aggressive ‘Knotweed’ that tangles us in the present, we advance, from the 16th century dissolution of the monasteries (or perhaps the Norman Conquest) to wars that are recognisably modern. The legacy of horsemen and bloodbaths gives way to marching black boots, trucks, and scattered airplane parts. But no bombs, drones, or missile button for the finger to press down, as in an image of grand-scale destruction that ends Primo Levi’s poem, ‘The Girl-Child of Pompeii’. While Levi takes us from Pompeii and natural disaster to the Nazi invasion and Hiroshima, Phillips takes us from the Norman Conquests to the Ukraine. In this, the second poem of the quartet, the flower, exceptionally, is given a geographical location. In ‘Ukraine Sunflower’ the butchery is relentless and the howling of dogs which are ‘something like wolves; so maybe Alsatians’ is a ceaseless chorus. It is resolved only at the end when the dogs are shot. Within this howling attack we stand in a debris-scorched field where the dead lie with their pockets emptied and pieces of a plane scattered round them. There is no exit and no salvation. Nor is there a reference to the peace found in the opening poem ‘Snowdrops’ and its opening stanza. Before the Norman Conquest, the holy ground of the shrine at Walsingham held ‘never-ending peace,/only the sounds of bells, the chantings and sheep’.

The unwelcome flower, ‘Knotweed’ – the speaker in the third poem – differs from the others. Allegorical, prophetic, Brechtian, knotweed is an authority with ‘roots deeper than you can dig.’ Also, it is up to date, informed by reports and images on YouTube. Embodying the hidden dangers of our world, from the Fukuskima Daiichi nuclear disaster to the New Terrorists, the Artic melt, and the invisible reach of the internet with its latest outrage of Smart meters, he warns us not to dream of winning. ‘You won’t find us but we are everywhere waiting.’

The final poem ‘Tulips’ is the most economical and the most explosive, although with the exception of ‘stomping’ and ‘grasped’, the verbs could not be quieter. We have the state-of-being verb ‘was’, then ‘looked’ ‘started’ ‘standing’ and ‘staring’. The speaker is not a flower but a child-survivor who has witnessed the approach of the tulips. The flowers are black. Iron crosses glitter on their tunics. And their marching black boots stomp. The poem leaves us with a childhood memory of flight. His mother grasped his hand. Then she turned to his father and said, ‘Come, we’re leaving today.’

In the Acumen poem, ‘A Bunch of Flowers’ – as in virtually all the flower-named poems in Gluck’s The Wild Iris, save for the title – the only references to flowers are indirect. In Phillips’ poem, the addressee is a ‘Mr White’, with whom we might associate any of 48 species of flowers called ‘Whites’. The name ‘White’ is colourless and stands for the ordinary citizen. The human Bob White shares his name with a common New World bird, rather than a flower. And we have a ‘bunch’, rather then a carefully arranged ‘bouquet’, representing a team of medical staff to take Bob White through heart surgery.

The speaker identifies himself as a surgeon. ‘Yes, that’s me’ he says informally, adding ‘from India” (line four) and checking that it is okay if he calls his patient by his first name, by which he means the shortened form of Bob and not the more substantial ‘Robert’.

In keeping with hospital protocol, the surgeon introduces his ‘bunch’. He names each member according to professional role and country of origin. We are in post-millennial Britain and most likely in a National Health Hospital. The medical bunch is an international one: its members come from India, Syria, Sri Lanka, Romania and Sweden. Not a Brit among them. These are the ‘flowers’ who care for the patient Bob White. He replies to the surgeon’s introduction as if he might have been presented with a nosegay of birdsong. Bob White says, ‘I think it all sounds rather beautiful.’ The surgeon continues with a sentence that linguists describe as Indianized English. He reduces and combines the closing of a formal letter (I look forward to hearing from you) with his intended outcome. Taking one more playful stop, the poet gives the doctor the last line and last word, ending with an adverb ‘strongly’ which is positioned so it takes the emphasis and rhymes with the doctor’s common Indian surname.

I think it all sounds rather beautiful, Mr Chakrabarti.

‘Thank you, Bob.

I look forward to hearing your heart beating strongly.’

With his low-keyed, understated but surprising manner, his subtle manipulation of the spoken, unobtrusive image and spare narrative, Peter Phillips buries bullets (if not land mines). They lie in the text like his snowdrops who didn’t see daylight for years and like Gluck’s Wild Iris who returns from oblivion ‘to find a voice’. Look out for FLOWERS and for Saying It With …

Joan Michelson picks her way through a few flower poems by Peter Phillips

[We can talk. ‘The Garden of Live Flowers’, (Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll, 1871)]

Reading these poems against the backdrop of Lewis Carroll and of the Pulitzer Prize 1993 collection, The Wild Iris by the American poet Louise Gluck, gives us a triple-take on the flower as voice for the human. Moreover, in their flower clusters, both Phillips and Gluck have ‘Snowdrop’ speakers. Without wanting to venture any distance into the tricky territory of Gluck’s metaphysics, ethics, and use of imagery, I found it helpful to approach his poem ‘Snowdrops’ from a look at hers.

Gluck’s ‘Snowdrops’ poem opens with despair, while Phillips has the flowers looking sad. Her snowdrop does not expect to survive because earth is suppressing it. Phillips’ snowdrops endure despite whole swathes being wiped out during the desecration of the sacred places that attracted them. After lying beneath wasted ground – some of them for many years – the small white bell flowers push up into the light. Gluck’s snowdrop ‘opens again’. Phillips’ snowdrops live on and his poem continues beyond renewal. Here the two poet-voices differ in ways that invite a separate essay. Gluck’s poem, like many in The Wild Iris, repositions us in the natural world. Phillips picks up the theme he has introduced earlier, extending the consequences of political upheaval, represented by the sacking and plundering of the monasteries of Walsingham and Framlingham. The snowdrops, though innocent, are part of it. They fall under the feet of the horsemen, under the bodies of the dead and lie in earth soaked with blood. Even in this earth, they regenerate, but this is not the only point made. They are victims because they are there and also they are witness-survivors, or the future generations of the survivors of the massacre. They live with their own trauma and say little about it. The relevance to our time hardly need be stated.

The two ‘Snowdrops’ poems end as follows:

crying yes risk joy in the raw wind of the new world. [Gluck] They hadn’t come for us but it was a bloodbath, we were part of it. No, talking doesn’t help. [Phillips]Phillips’ poem makes an imaginative connection with flowers; its tendrils reach out, the touch consistently light and minimal, into history. Each of the poems in the Hearing Eye pamphlet takes the name of a flower for its title: besides ‘Snowdrops’ we find ‘Ukraine Sunflower’. ‘Knotweed’ and ‘Tulips’.

The tulips are black and the march of their black boots is the touchstone image recreated by Emily Johns to introduce the poems. The pamphlet opens to a front-page spread of black tulip figures in march formation. In her VW leaf-leg design, they call up the emblem of the Volkswagen Beetle, Hitler’s car ‘for the people’. A bright translucent blood-red smear runs across the collective lower body as if held in place by a row of invisible hands, and in this we might see a Party banner. The material, like a fine-weave cotton or muslin-silk, from which banners are made, thins out and falls away as it trails towards the back. Like a political banner which carries a slogan, a message is printed on it. FLOWERS stands out in large capital letters, surrounded by the pamphlet title and author’s name. The banner could represent the Communist one, with hammer and sickle missing, or a National Socialist one with swastika missing, or the unadorned sign of the 18th century French Revolutionaries.

Emily John’s linocut illustration is as powerful and expansive as the texts that follow. From ‘Snowdrops’ to ‘Tulips’, interrupted by the aggressive ‘Knotweed’ that tangles us in the present, we advance, from the 16th century dissolution of the monasteries (or perhaps the Norman Conquest) to wars that are recognisably modern. The legacy of horsemen and bloodbaths gives way to marching black boots, trucks, and scattered airplane parts. But no bombs, drones, or missile button for the finger to press down, as in an image of grand-scale destruction that ends Primo Levi’s poem, ‘The Girl-Child of Pompeii’. While Levi takes us from Pompeii and natural disaster to the Nazi invasion and Hiroshima, Phillips takes us from the Norman Conquests to the Ukraine. In this, the second poem of the quartet, the flower, exceptionally, is given a geographical location. In ‘Ukraine Sunflower’ the butchery is relentless and the howling of dogs which are ‘something like wolves; so maybe Alsatians’ is a ceaseless chorus. It is resolved only at the end when the dogs are shot. Within this howling attack we stand in a debris-scorched field where the dead lie with their pockets emptied and pieces of a plane scattered round them. There is no exit and no salvation. Nor is there a reference to the peace found in the opening poem ‘Snowdrops’ and its opening stanza. Before the Norman Conquest, the holy ground of the shrine at Walsingham held ‘never-ending peace,/only the sounds of bells, the chantings and sheep’.

The unwelcome flower, ‘Knotweed’ – the speaker in the third poem – differs from the others. Allegorical, prophetic, Brechtian, knotweed is an authority with ‘roots deeper than you can dig.’ Also, it is up to date, informed by reports and images on YouTube. Embodying the hidden dangers of our world, from the Fukuskima Daiichi nuclear disaster to the New Terrorists, the Artic melt, and the invisible reach of the internet with its latest outrage of Smart meters, he warns us not to dream of winning. ‘You won’t find us but we are everywhere waiting.’

The final poem ‘Tulips’ is the most economical and the most explosive, although with the exception of ‘stomping’ and ‘grasped’, the verbs could not be quieter. We have the state-of-being verb ‘was’, then ‘looked’ ‘started’ ‘standing’ and ‘staring’. The speaker is not a flower but a child-survivor who has witnessed the approach of the tulips. The flowers are black. Iron crosses glitter on their tunics. And their marching black boots stomp. The poem leaves us with a childhood memory of flight. His mother grasped his hand. Then she turned to his father and said, ‘Come, we’re leaving today.’

In the Acumen poem, ‘A Bunch of Flowers’ – as in virtually all the flower-named poems in Gluck’s The Wild Iris, save for the title – the only references to flowers are indirect. In Phillips’ poem, the addressee is a ‘Mr White’, with whom we might associate any of 48 species of flowers called ‘Whites’. The name ‘White’ is colourless and stands for the ordinary citizen. The human Bob White shares his name with a common New World bird, rather than a flower. And we have a ‘bunch’, rather then a carefully arranged ‘bouquet’, representing a team of medical staff to take Bob White through heart surgery.

The speaker identifies himself as a surgeon. ‘Yes, that’s me’ he says informally, adding ‘from India” (line four) and checking that it is okay if he calls his patient by his first name, by which he means the shortened form of Bob and not the more substantial ‘Robert’.

In keeping with hospital protocol, the surgeon introduces his ‘bunch’. He names each member according to professional role and country of origin. We are in post-millennial Britain and most likely in a National Health Hospital. The medical bunch is an international one: its members come from India, Syria, Sri Lanka, Romania and Sweden. Not a Brit among them. These are the ‘flowers’ who care for the patient Bob White. He replies to the surgeon’s introduction as if he might have been presented with a nosegay of birdsong. Bob White says, ‘I think it all sounds rather beautiful.’ The surgeon continues with a sentence that linguists describe as Indianized English. He reduces and combines the closing of a formal letter (I look forward to hearing from you) with his intended outcome. Taking one more playful stop, the poet gives the doctor the last line and last word, ending with an adverb ‘strongly’ which is positioned so it takes the emphasis and rhymes with the doctor’s common Indian surname.

With his low-keyed, understated but surprising manner, his subtle manipulation of the spoken, unobtrusive image and spare narrative, Peter Phillips buries bullets (if not land mines). They lie in the text like his snowdrops who didn’t see daylight for years and like Gluck’s Wild Iris who returns from oblivion ‘to find a voice’. Look out for FLOWERS and for Saying It With …

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2016 0 • Tags: books, Joan Michelson, poetry