Thomas Ovans admires Rhona McAdam for finding many poetic ways of looking backwards at places, people and formative experiences

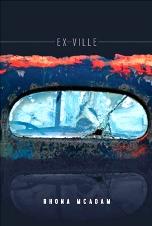

Ex-Ville

Ex-Ville

Rhona McAdam

Oolichan Books (British Columbia)

ISBN 978-0-88982-306-8

80 pp $17.95

Rhona McAdam is a Canadian poet, almost as well-known in London as in her native British Columbia. She lived in London for many years and has recently been here again giving readings from her latest collection Ex-Ville. As might be deduced from the title, the book contains poems about looking backwards – to places, to departed family and friends, to relationships and to one’s own former self.

The book’s first two poems set the bar very high. ‘Back When’ captures vividly the balloon of youthful self-confidence – We had no sense / then of frailty – when old backgrounds were reliable and comforting

Our parents were alive and we

immortal. Family pets,

white-muzzled,

still purred and slobbered

at the edges of homecomings.

All this is eventually punctured when we are awakened (literally) to the truth about mortality:

The phone pierced our sleep

At all hours

The consequences of such phone calls are movingly addressed in later poems.

‘Scatterling’, the second poem, deals convincingly with remembered links to significant places, substantiating an initial claim (or is it merely a hope?) that I live on in London.

Crumbs of me on the windowsill, my face

caught between blinds, looking out

to check the weather. My past keeps slipping

out at lunchtime, its errands urgent and forgotten.

McAdam has a deft way with line breaks: notice how the seemingly self-contained observation My past keeps slipping shifts its meaning as the next line begins. She has already played a similar trick on us in the previous poem with the line We had no sense.

‘Scatterling’ is the first of many poems about places visited, places left behind and the act of travelling between the one and the other. McAdam seeks to deal with these topics in a variety of ways, particularly in the last third of the book. ‘Summer Getaway’ includes a delightfully dead-pan reflection on passports –

We are codes and numbers and holograms.

We may no longer smile.

We must be known to figures of authority

for two years: we may have paid

to have them say so.

‘Getting There’, on the other hand, is a rather melancholy and eccentric guided tour of an old home town which carefully takes in all the landmarks which are no longer there

Turn where the Eaton’s store was

and cross at the lights, where the four-way

stop used to be,

next to the former home of the farmers’ market.

Similarly eccentric is ‘The Phantom Bus’ – Now that its existence has been questioned /it no longer comes.

A different and darker travelling poem is ‘Furlough’ – a powerful reported speech account of an in-flight meeting with a US soldier on leave from service in the Middle East. He is looking forward to two years time when he’s pretty sure /they can’t call him back again; but he must moderate his hopes because rules /change, he knows, in times of war. This is a convincing voice and a fairly rare example of McAdam stepping outside her own frame of reference (another is ‘The Obituarist’ discussed below).

‘Furlough’ demonstrates to me that McAdam’s writing is often at its very best when people are in the foreground; and thus it is in the middle section of the book that she most consistently hits her stride. Here we find a group of poems about a relationship and its ending which is cleverly preceded with a sidelong look at the synthetic emotions of Country and Western music. In ‘Bluegrass’ we learn that God / blessed misfortune / and gave it a single microphone – through which a typical refrain is Oh lonesome lonesome lonesome / is the night and where the narrative is frequently It never rains but it pours, never pours / but we’re washed by the flood. In contrast, ‘Dysphasia’ conveys the chillingly undramatic nature of separation in real life:

Your silence was with me all week.

…

On Sunday your silence rose up and walked with me

it had a life and a plausible history

I explained to it as we followed

The trail I always meant to show you.

The recovery from loss – or rather the re-making of self – is slow and is spelled out in an elegant pantoum ‘High Tides’: I’ve swum free of my body; I’m buried at sea; / gone is the body you held in those hands.

And an eventual backlash comes in ‘Spring Cleaning’ with its well-sustained central fantasy

I’ve hung the shirt you left

head down on the line

…

I’ll see you in tatters

battered shapeless by a wind

…

I plan to leave you there

till the sky burrows

through your heart

Other fine poems at the heart of the book are prefigured by that late-night phone call in ‘Back When’ and deal with the heartaches of looking after elderly parents as they decline into physical and mental frailty. In ‘Lost’, McAdam skilfully uses experiences her readers may find familiar in order to approximate the confusions of dementia by the feeling of being lost in a strange city or unable to find the right entrance to a re-modelled hospital (we spent twenty minutes / traversing the old parking lot). In ‘Extended Care’, the promotion of image over substance – in healthcare as in so much else – is neatly skewered. The old sort of nursing home was simply the place where mothers go. But now things have changed: They put a capital letter / in Home, and that made all the difference.

As can be seen from the quoted extracts, most of the poems are in the first person (singular or plural); but the book contains some well-judged exceptions, such as ‘Furlough’ and a wonderfully eerie poem about ‘The Obituarist’. This seems at first to be oddly out of place – until one realises that to be an obituarist is to make a profession out of looking backwards. This particular practitioner gleans the manner of each death and then paddles his cargo of words / across still waters until at last he drops their secrets in the lake, and the loons / tell them back to him. Elsewhere, McAdam can take inanimate objects like photographs or doors and construct a meditation as eloquent as an overtly (first- or third-) personal expression of emotion.

There is of course a risk that a book constructed largely around regretful hindsight may at times prove to be heavy going. But for the most part McAdam manages to avoid building up a cumulative sense of bleakness and shuns the negativity of self-centredness. ‘I Raise a Glass’ sensitively tackles the painful subject of childlessness by giving as much attention to the unborn children as to the feelings of the narrator. And ‘Every Good Boy Deserves Favour’ takes the lesser disappointment of being unable (after many lessons) to master the piano and turns it into rueful admiration for those who could successfully lift the lid /on this box of suffering. The underlying sadness of much of the material is consistently counter-balanced by adroit and often dry observations, like the journey on a Greyhound bus that is a race / against comfort. I suspect that many readers will discover episodes from their own lives being illuminated by McAdam’s carefully crafted imagery and insight.

.

Thomas Ovans has a background as an academic and technical writer but has been a serious reader of poetry for a quarter of a century. Since 2011 he has been a book reviewer for London Grip; and he is now also an occasional poet whose work has been published in both on-line and print magazines.

Thomas Ovans admires Rhona McAdam for finding many poetic ways of looking backwards at places, people and formative experiences

Rhona McAdam

Oolichan Books (British Columbia)

ISBN 978-0-88982-306-8

80 pp $17.95

Rhona McAdam is a Canadian poet, almost as well-known in London as in her native British Columbia. She lived in London for many years and has recently been here again giving readings from her latest collection Ex-Ville. As might be deduced from the title, the book contains poems about looking backwards – to places, to departed family and friends, to relationships and to one’s own former self.

The book’s first two poems set the bar very high. ‘Back When’ captures vividly the balloon of youthful self-confidence – We had no sense / then of frailty – when old backgrounds were reliable and comforting

Our parents were alive and we

immortal. Family pets,

white-muzzled,

still purred and slobbered

at the edges of homecomings.

All this is eventually punctured when we are awakened (literally) to the truth about mortality:

The phone pierced our sleep

At all hours

The consequences of such phone calls are movingly addressed in later poems.

‘Scatterling’, the second poem, deals convincingly with remembered links to significant places, substantiating an initial claim (or is it merely a hope?) that I live on in London.

Crumbs of me on the windowsill, my face

caught between blinds, looking out

to check the weather. My past keeps slipping

out at lunchtime, its errands urgent and forgotten.

McAdam has a deft way with line breaks: notice how the seemingly self-contained observation My past keeps slipping shifts its meaning as the next line begins. She has already played a similar trick on us in the previous poem with the line We had no sense.

‘Scatterling’ is the first of many poems about places visited, places left behind and the act of travelling between the one and the other. McAdam seeks to deal with these topics in a variety of ways, particularly in the last third of the book. ‘Summer Getaway’ includes a delightfully dead-pan reflection on passports –

We are codes and numbers and holograms.

We may no longer smile.

We must be known to figures of authority

for two years: we may have paid

to have them say so.

‘Getting There’, on the other hand, is a rather melancholy and eccentric guided tour of an old home town which carefully takes in all the landmarks which are no longer there

Turn where the Eaton’s store was

and cross at the lights, where the four-way

stop used to be,

next to the former home of the farmers’ market.

Similarly eccentric is ‘The Phantom Bus’ – Now that its existence has been questioned /it no longer comes.

A different and darker travelling poem is ‘Furlough’ – a powerful reported speech account of an in-flight meeting with a US soldier on leave from service in the Middle East. He is looking forward to two years time when he’s pretty sure /they can’t call him back again; but he must moderate his hopes because rules /change, he knows, in times of war. This is a convincing voice and a fairly rare example of McAdam stepping outside her own frame of reference (another is ‘The Obituarist’ discussed below).

‘Furlough’ demonstrates to me that McAdam’s writing is often at its very best when people are in the foreground; and thus it is in the middle section of the book that she most consistently hits her stride. Here we find a group of poems about a relationship and its ending which is cleverly preceded with a sidelong look at the synthetic emotions of Country and Western music. In ‘Bluegrass’ we learn that God / blessed misfortune / and gave it a single microphone – through which a typical refrain is Oh lonesome lonesome lonesome / is the night and where the narrative is frequently It never rains but it pours, never pours / but we’re washed by the flood. In contrast, ‘Dysphasia’ conveys the chillingly undramatic nature of separation in real life:

Your silence was with me all week.

…

On Sunday your silence rose up and walked with me

it had a life and a plausible history

I explained to it as we followed

The trail I always meant to show you.

The recovery from loss – or rather the re-making of self – is slow and is spelled out in an elegant pantoum ‘High Tides’: I’ve swum free of my body; I’m buried at sea; / gone is the body you held in those hands.

And an eventual backlash comes in ‘Spring Cleaning’ with its well-sustained central fantasy

I’ve hung the shirt you left

head down on the line

…

I’ll see you in tatters

battered shapeless by a wind

…

I plan to leave you there

till the sky burrows

through your heart

Other fine poems at the heart of the book are prefigured by that late-night phone call in ‘Back When’ and deal with the heartaches of looking after elderly parents as they decline into physical and mental frailty. In ‘Lost’, McAdam skilfully uses experiences her readers may find familiar in order to approximate the confusions of dementia by the feeling of being lost in a strange city or unable to find the right entrance to a re-modelled hospital (we spent twenty minutes / traversing the old parking lot). In ‘Extended Care’, the promotion of image over substance – in healthcare as in so much else – is neatly skewered. The old sort of nursing home was simply the place where mothers go. But now things have changed: They put a capital letter / in Home, and that made all the difference.

As can be seen from the quoted extracts, most of the poems are in the first person (singular or plural); but the book contains some well-judged exceptions, such as ‘Furlough’ and a wonderfully eerie poem about ‘The Obituarist’. This seems at first to be oddly out of place – until one realises that to be an obituarist is to make a profession out of looking backwards. This particular practitioner gleans the manner of each death and then paddles his cargo of words / across still waters until at last he drops their secrets in the lake, and the loons / tell them back to him. Elsewhere, McAdam can take inanimate objects like photographs or doors and construct a meditation as eloquent as an overtly (first- or third-) personal expression of emotion.

There is of course a risk that a book constructed largely around regretful hindsight may at times prove to be heavy going. But for the most part McAdam manages to avoid building up a cumulative sense of bleakness and shuns the negativity of self-centredness. ‘I Raise a Glass’ sensitively tackles the painful subject of childlessness by giving as much attention to the unborn children as to the feelings of the narrator. And ‘Every Good Boy Deserves Favour’ takes the lesser disappointment of being unable (after many lessons) to master the piano and turns it into rueful admiration for those who could successfully lift the lid /on this box of suffering. The underlying sadness of much of the material is consistently counter-balanced by adroit and often dry observations, like the journey on a Greyhound bus that is a race / against comfort. I suspect that many readers will discover episodes from their own lives being illuminated by McAdam’s carefully crafted imagery and insight.

.

Thomas Ovans has a background as an academic and technical writer but has been a serious reader of poetry for a quarter of a century. Since 2011 he has been a book reviewer for London Grip; and he is now also an occasional poet whose work has been published in both on-line and print magazines.

By Michael Bartholomew-Biggs • books, poetry reviews, year 2015 1