Poetry Review – WHEREOF: Jennifer Johnson discovers what she thinks about the philosophical poetry of Christopher Norris

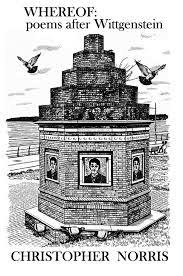

WHEREOF: poems after Wittgenstein

WHEREOF: poems after Wittgenstein

Christopher Norris

Cambria Books

ISBN 978-1-9192698-2-5

182 pp £18.00

Christopher Norris is a philosopher-poet who lives in Swansea and is an Emeritus Distinguished Professor at Cardiff University. He has published many books on philosophy and, more recently, verse-collections on the philosophers Rilke, Derrida, Walter Benjamin and Adorno. WHEREOF: poems after Wittgenstein is his latest verse-collection on a philosopher, in this case, the most influential philosopher in the Anglophone tradition. Norris has taught and written about Wittgenstein extensively for over 40 years. This book, which consists of 62 poems and verse-essays, is accessible to readers who, like me, have a limited knowledge of Wittgenstein; but those with a greater knowledge will be able to compare these reflections with those of other commentators. It is, as Norris says in his introduction, ‘primarily a book of poetry rather than an academic treatise’ but he does also ‘intend this sequence as a contribution to philosophical debate around Wittgenstein’s thought’. This changed between his early Tractatus and his later Philosophical Investigations.

The biographical facts and ideas of Wittgenstein are summarised in the clearly written introduction as are the contrary views of Norris particularly on the subject of Wittgenstein’s notion of ‘language games’, language under ‘communal control’ as described in “On linguistic bewitchment” or, in the Wittgenstein epigraph that begins the poem “Meaning and use” in the statement that ‘The meaning of a word is its use in the language. Don’t ask for the meaning; ask for the use’. Each poem or verse-essay begins with one or more epigraphs by Wittgenstein followed by a response either in his own voice, or that of Norris or that of someone else, including at times a ‘jovial scold’. For those less familiar with the work of Wittgenstein an internet search may help locate the source of these epigraphs. A search may also be useful, for some, to find the meanings of the odd obscure word or idiom.

Wittgenstein states that ‘philosophy should only be written as poetry’ and Norris has taken him at his word, writing responses to Wittgenstein’s epigraphs as poetry but of a type different to the type Wittgenstein would have been thinking of, which would have been a poetry foregrounded in metaphor, image and symbol such as that written by Rilke and Hölderlin. For Norris, this type of poetry is unsuitable for writing ‘verse-reflections’ for as he puts it in “Philosophy, language, music Part III”, it is a type of poetry ‘they’d have us glad / To feel, not think too clearly.’ Norris, therefore, writes the responses in formal verse where argument is foregrounded. In the Introduction Norris writes that rhyme and metre ‘embody poetry’s claim to have its own specific angle – or point d’appui – on what’s left unexamined, or not fully brought out, in prose discourse.’ The music of the skilfully written formal verse in this collection also gives the reader greater pleasure than something similar written in prose. Perhaps surprisingly for a renowned expert on Derrida, Norris clearly enjoys the challenge of writing complex poetic forms such as villanelles, sestinas and double sestinas. The wit shown in many of the poems also makes this collection one that should make the reader smile. Take the 4-line poem near the beginning of the book “Philosophical Jokes” which begins with the Wittgenstein epitaph ‘A serious and good philosophical work could be written entirely of jokes.’ The response that follows is

True no doubt, Ludwig, but one might demur

Should someone say ‘why didn’t Wittgenstein

Give us a few?’, while wiser folk concur:

‘Smart-ass one-liners? Really not his line’.

This poem, as well as showing some gentle wit, also draws attention to the gap between what Wittgenstein said and did. This is a theme comes up in several verse-essays as well as in the introduction which points the contradiction between Wittgenstein’s obsession with ‘language games’ which allow for no ‘private language’ and his intense need for privacy. Such contradictions make Wittgenstein human and like most real people he had psychological problems. In “Life, death, timelessness – and Hell” one of the Wittgenstein epigraphs states that ‘Hell isn’t other people. Hell is yourself.’ In the final verse-essay “A wonderful life…” there is another apparent contradiction. The Wittgenstein epigraph at the beginning exhorts, ‘Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life…’. One of the repeated questions later in the response is, ‘How conjure paradise from psychic hell?’ The start of the response, however, begins ‘So many ways those last words might be meant!’ In an earlier poem “Trying to say the whole thing”, Wittgenstein expresses anxiety about seeing things ‘from different angles’. Norris, in his response to this poem, reveals his own identification as an Empsonian by quoting the last line of Empson’s “Let It Go” in the response’s final line, ‘You don’t want madhouse and the whole thing there’. Norris also mentions a sympathetic Empson at the beginning of the response ‘Bill Empson, whom you knew, said don’t despair:’. Wittgenstein feared madness and had no time for Freud; and these themes are explored in “Death, insanity, and ‘taking for granted”. . Despite the number of poems and verse-essays that counter Wittgenstein’s statements, Norris describes the famous philosopher as a ‘fascinating writer.’ All the same he acknowledges what he considers his later failings and his creation of a ‘language turn’ which, he says, eventually led to harmful notions such as ‘post-truth’. Wittgenstein not only wrote on the philosophy of language in the verbal sense but also about music, science and mathematics. Responses to statements on these subjects appear in poems such as “Wittgenstein, Gödel, Turing”. Wittgenstein’s movement away from formal logic is shown in his Tractatus is expressed in Part IV.

They do me wrong, the mathematikoi,

Conceive no game but theirs correctly played!

Place logic centre-stage, their usual ploy.

I would highly recommend WHEREOF: poems after Wittgenstein as either as a poetic introduction to Wittgenstein or, for those who know more, a challenge to received notions on Wittgenstein. As this is firstly a collection of poems readers should enjoy most the skilful formal verse.

Feb 15 2026

London Grip Poetry Review – Christopher Norris

Poetry Review – WHEREOF: Jennifer Johnson discovers what she thinks about the philosophical poetry of Christopher Norris

Christopher Norris

Cambria Books

ISBN 978-1-9192698-2-5

182 pp £18.00

Christopher Norris is a philosopher-poet who lives in Swansea and is an Emeritus Distinguished Professor at Cardiff University. He has published many books on philosophy and, more recently, verse-collections on the philosophers Rilke, Derrida, Walter Benjamin and Adorno. WHEREOF: poems after Wittgenstein is his latest verse-collection on a philosopher, in this case, the most influential philosopher in the Anglophone tradition. Norris has taught and written about Wittgenstein extensively for over 40 years. This book, which consists of 62 poems and verse-essays, is accessible to readers who, like me, have a limited knowledge of Wittgenstein; but those with a greater knowledge will be able to compare these reflections with those of other commentators. It is, as Norris says in his introduction, ‘primarily a book of poetry rather than an academic treatise’ but he does also ‘intend this sequence as a contribution to philosophical debate around Wittgenstein’s thought’. This changed between his early Tractatus and his later Philosophical Investigations.

The biographical facts and ideas of Wittgenstein are summarised in the clearly written introduction as are the contrary views of Norris particularly on the subject of Wittgenstein’s notion of ‘language games’, language under ‘communal control’ as described in “On linguistic bewitchment” or, in the Wittgenstein epigraph that begins the poem “Meaning and use” in the statement that ‘The meaning of a word is its use in the language. Don’t ask for the meaning; ask for the use’. Each poem or verse-essay begins with one or more epigraphs by Wittgenstein followed by a response either in his own voice, or that of Norris or that of someone else, including at times a ‘jovial scold’. For those less familiar with the work of Wittgenstein an internet search may help locate the source of these epigraphs. A search may also be useful, for some, to find the meanings of the odd obscure word or idiom.

Wittgenstein states that ‘philosophy should only be written as poetry’ and Norris has taken him at his word, writing responses to Wittgenstein’s epigraphs as poetry but of a type different to the type Wittgenstein would have been thinking of, which would have been a poetry foregrounded in metaphor, image and symbol such as that written by Rilke and Hölderlin. For Norris, this type of poetry is unsuitable for writing ‘verse-reflections’ for as he puts it in “Philosophy, language, music Part III”, it is a type of poetry ‘they’d have us glad / To feel, not think too clearly.’ Norris, therefore, writes the responses in formal verse where argument is foregrounded. In the Introduction Norris writes that rhyme and metre ‘embody poetry’s claim to have its own specific angle – or point d’appui – on what’s left unexamined, or not fully brought out, in prose discourse.’ The music of the skilfully written formal verse in this collection also gives the reader greater pleasure than something similar written in prose. Perhaps surprisingly for a renowned expert on Derrida, Norris clearly enjoys the challenge of writing complex poetic forms such as villanelles, sestinas and double sestinas. The wit shown in many of the poems also makes this collection one that should make the reader smile. Take the 4-line poem near the beginning of the book “Philosophical Jokes” which begins with the Wittgenstein epitaph ‘A serious and good philosophical work could be written entirely of jokes.’ The response that follows is

True no doubt, Ludwig, but one might demur

Should someone say ‘why didn’t Wittgenstein

Give us a few?’, while wiser folk concur:

‘Smart-ass one-liners? Really not his line’.

This poem, as well as showing some gentle wit, also draws attention to the gap between what Wittgenstein said and did. This is a theme comes up in several verse-essays as well as in the introduction which points the contradiction between Wittgenstein’s obsession with ‘language games’ which allow for no ‘private language’ and his intense need for privacy. Such contradictions make Wittgenstein human and like most real people he had psychological problems. In “Life, death, timelessness – and Hell” one of the Wittgenstein epigraphs states that ‘Hell isn’t other people. Hell is yourself.’ In the final verse-essay “A wonderful life…” there is another apparent contradiction. The Wittgenstein epigraph at the beginning exhorts, ‘Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life…’. One of the repeated questions later in the response is, ‘How conjure paradise from psychic hell?’ The start of the response, however, begins ‘So many ways those last words might be meant!’ In an earlier poem “Trying to say the whole thing”, Wittgenstein expresses anxiety about seeing things ‘from different angles’. Norris, in his response to this poem, reveals his own identification as an Empsonian by quoting the last line of Empson’s “Let It Go” in the response’s final line, ‘You don’t want madhouse and the whole thing there’. Norris also mentions a sympathetic Empson at the beginning of the response ‘Bill Empson, whom you knew, said don’t despair:’. Wittgenstein feared madness and had no time for Freud; and these themes are explored in “Death, insanity, and ‘taking for granted”. . Despite the number of poems and verse-essays that counter Wittgenstein’s statements, Norris describes the famous philosopher as a ‘fascinating writer.’ All the same he acknowledges what he considers his later failings and his creation of a ‘language turn’ which, he says, eventually led to harmful notions such as ‘post-truth’. Wittgenstein not only wrote on the philosophy of language in the verbal sense but also about music, science and mathematics. Responses to statements on these subjects appear in poems such as “Wittgenstein, Gödel, Turing”. Wittgenstein’s movement away from formal logic is shown in his Tractatus is expressed in Part IV.

They do me wrong, the mathematikoi,

Conceive no game but theirs correctly played!

Place logic centre-stage, their usual ploy.

I would highly recommend WHEREOF: poems after Wittgenstein as either as a poetic introduction to Wittgenstein or, for those who know more, a challenge to received notions on Wittgenstein. As this is firstly a collection of poems readers should enjoy most the skilful formal verse.