Jan 15 2026

London Grip Poetry Review -Liz Robbins

Poetry review – BACKLIT: Charles Rammelkamp reviews a prize-winning collection by Liz Robbins which explores the emotions and fears behind the anonymity of sex-workers

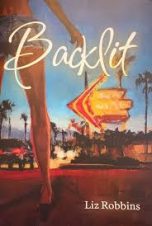

Backlit Liz Robbins Rattle, 2025 ISBN: 978-1-931307-63-5 $9.00 44 pages

Dedicated to “the powerless,” most of the two dozen poems that make up Liz Robbins’ Rattle Chapbook Prize-winning collection are in the voice of a reluctant sex worker, a girl forced into this life by financial and social circumstances, the deck stacked against her. “This Game Is a Rip,” indeed, as the title of the first poem tells us. In “Smell of Pitch” she tells us, ‘I started

tricking at fourteen because my mom needed more money and my sisters were still young.

She goes on to describe the life, leaning against a lamppost, ‘feet jammed into white high heels,’ while guys driving by in trucks drinking beer, inspected the goods. The setting is Florida. The poem ends wistfully, ‘Someday, I’ll build a / cabin in the forest, and I’ll hear and feel and fear nothing.’ Escape is a fantasy never far from her thoughts.

And fear is indeed a motivating factor, as she mentions again and again in the poems. In “Small Towns,” for instance, it’s fear that prompts her instinct to submit, the easy way out. In “Element of Conflict” she writes

Tell me, do I feel dread or relief when the unwashed truck cruises to a halt? Is it just me, or me against men?

In the third of four poems titled “Sex Worker,” she writes, ‘The job is more dangerous

than fishing Alaska’s icy seas or felling redwoods. I get attacked once a month. But going to the cops means I’ve turned myself in. Instead, in red nails and heels, I turn myself out—

Violence is a constant part of the life. In “Desert Scene,” Robbins subtly underscores this in an opening simile: ‘The night black as an eye.’

A character named Pimp Mike floats in and out of the poems – between “Dilemmas,” the first “Sex Worker” poem, and “Clean.” In “Family,” ‘Pimp Mike tells us girls / again we’re like a close family.’ But of course he’s more like a boss or an overseer on a plantation than a caring father or jolly uncle. While the protagonist doesn’t particularly enjoy her work, she knows if she spelled this out to the john,

Pimp Mike would be mad. Mike says we girls

are lucky to choose—how many men

a day, five to ten. But we all know his favorite girls are tens.

But Robbins is not so much interested in painting a lurid picture of sex trafficking as she is in getting inside the head of this unnamed sex worker, the hopelessness she feels, the escape she seeks. ‘All our / lives, we are left by people, and our work is to keep finding more,’ she writes in “Runaways.” She bonds with others in the “family,” but it’s a revolving door, no friendships or alliances are permanent. Jade is a partner in “War,” giving the protagonist advice on the proper attitude (‘think of it as an art’). And in “Runaways” it’s Cara she confides in (‘We complain about the johns, and in our likenesses, feel love for / each other, feel understood’). But there’s nobody she can count on. ‘I always wonder when

Cara will leave me. Who will come next? There is no one right way to walk through this life. Yet no one told me at fourteen what I was really choosing to hold close was the squeal of brakes, a sound of resistance, like hinges when a door slams shut.

In the final “Sex Worker” poem, the protagonist describes three different personalities that inhabit her. It’s nothing schizophrenic, but it highlights the confusion and alienation that she feels. First, there’s the prostitute.

As I began inside me sat an adolescent trained (however gently) to use her brown eyes, breasts, soft hair to influence: eventually, having strange sex with strange men in exchange for cash…

But there is also something pure, a part of her that is not transactional but aloof, a kind of martyr:

Also inside me a nun, a girl of a kind who still hoped, trusted life could grow better…

And finally, there’s the cynic who sees the whole situation “as it is,” no fooling herself, no disguising the reality:

Also inside me a clown, who found the nun and whore naïve and abused, brutal outcomes, cartoon extremes like himself under life’s big-top: punchlines that felt familiar…

In “Daphne Swimming” the protagonist channels the transformation myth from Ovid’s Metamorphosis in which the nymph Daphne becomes a laurel tree in order to escape Apollo. All men are Apollo in her world. Running away is her dream.

Robbins backlights the protagonist as she moves across the stage, highlighting the subtle forces that make her destiny what it is. In the last poem in Backlit, “Clean,” in which Pimp Mike makes a final appearance, the protagonist confesses, ‘I take hot baths, one after each john, five or six / a day.’ In her fantasy, ‘I am very young, / almost embryonic,’ and she thinks of her mother and father as though she were being scrubbed clean, ‘touching me pristine and in places / a tender feeling is not so strange.’ It’s the ultimate escape: denial.

16/01/2026 @ 15:41

Much appreciation for this review!