Poetry Review – OBJECT PERMANENCE: D A Prince admires the perceptive insights that Anne Berkeley uses and explains in this collection of well-observed poems

Object Permanence

Object Permanence

Anne Berkeley

The Garlic Press, 2025

ISBN 978-1-0682630-0-2

80pp £12.00

Object Permanence is a perfect title for a collection centred on looking, watching, observing and remembering. If the concept is unfamiliar the collection’s Notes give a helpful definition as follows: ‘Object permanence’ is the understanding that objects can continue to exist even when we cannot perceive them. ‘La permanence de l’objet’ described by Jean Piaget is a milestone in child development.’

We, as adults, take this for granted: we can intuitively balance the visual memory of objects and places against their absence. This, however, is a learned skill which we don’t remember learning; so much is happening in those early years. Berkeley’s poems have now placed the idea in front of me, adding depth to the levels of attentiveness poets — and their readers — bring to poems.

The collection culminates in two poems that engage directly with this, with “Object permanence” as the final poem. It’s satisfying, as though the experiences described in earlier poems have finally been brought together, and in a way that reminds us how much we assume in regard to perception. But let’s start at the beginning, with the foundations. Berkeley does not write about theories of perception: she demonstrates them. Her poems are rooted in personal memory, with clarity, immediacy, and a sharpness of recall matched by the precision of her vocabulary and syntax. There’s a depth to the layering of memory in these poems that readers will recognise and share. Her poems have a wider range of reference than might appear on the surface. She’s able, too, to nod to her readings of other poets with a light touch only visible to the alert reader; again, ‘satisfying’ seems the appropriate description.

The past can be a list and while the opening poem, “Places I have slept”, is her list it also manages to draw in the reader, with that unspoken question: and what about you?

I slept in the top bunk, in the bottom bunk

in a tent, in another tent, in so many tents

in the peppering, sheeting rain

I slept on the bus

There’s no anecdotal context, nothing to explain the variety of places, and few adjectives — ‘peppering, sheeting rain’ is a rare example. Somehow those two adjectives expand, attaching their discomfort to other places, other beds. It sets the tone: this will be a plain-speaking, clear-sighted collection with a long view back down the years.

Childhood is fertile ground for recall. In the longest poem, “Gibraltar Point”, three pages in a child’s voice, Berkeley’s use of the present tense and minimal punctuation brings a seaside trip to life with a salty relish for the rhythms of a child’s speech patterns. It’s a headlong rush in just two sentences, the first rattling through the journey

Can you smell the sea he’ll ask and we all

say yes though we don’t know what the sea

smells like we think maybe it smells of fish

and chips and we finally get to the Skegness

is So Bracing fat sailor dainty on the big sign

long before houses then holiday shops with

shrimping nets and union jacks for sandcastles

but We’re Not There Yet we’re not stopping here

This equal placing of sounds and smells mirrors the way a child can hold them all in play simultaneously. The line breaks after ‘fish’, and then after ‘Skegness’, are teasing and fun. No italics for direct speech: again, this is a nod to a child’s way of recording. The Skegness railway poster (aka ‘The Jolly Fisherman’, commissioned in 1908) promoted Skegness for decades at railway stations, became the town’s mascot and now has its own Wikipedia page. The second sentence, the family car now parked (‘If there are no other cars/ it’s Good but we’re not there yet …’) rattles through the activities the carrying, running, squabbling, beach-combing, the hoping for ice-cream,: all the sensations of two children on a rare day by the sea. You can taste the salt.

Berkeley trusts her readers. “The away match” is, on first reading, a slight anecdote: on the second reading Berkeley’s lack of awareness of her social gaucheness is evident. It’s one of those rare poems where the reader is just slightly ahead of the poet; few can achieve this and I treasure those poems where it appears. By contrast “You only live twice” shows Berkeley’s late-in-the-day understanding of herself: on her Saturday shift in an antique shop she’s puzzled as a young man lingers, trying to decide on a purchase, the prices, engaging her in seemingly irrelevant conversation

Paul, it’s taken me until I’m practically antique

for the penny to drop:

what you were looking for,

how much it must have cost you.

Layers of time overlap via the most ordinary sights. In “Dirty old wheelbarrow” she watches delivery drivers unloading outside a hardware shop

Barrow after barrow trundles round the back

past washing lines, Atco mowers, Calor Gas,

to where my father’s shifting rubble

in the fifties. He’s just made a window

in the kitchen wall, to let in the morning

Who hasn’t been surprised at a similar linkage in their own memory? Among the connections to friends, named and un-named, is “The man who made poems: for R”. I recognised ‘R’ from the details given:

A man who knew things. Names of plants and knots. Works of Josephus and Scriabin.

Who made things: boxes, collages, casseroles, and salads …

[…]

Who replaced his rainbow jumper with a black one on the last day.

Anyone who remembers Roy Blackman, poet and co-editor of the poetry magazine Smiths Knoll, will remember that jumper, along with his innate modesty and kindness to poets. He died in 2002 and this is an eloquent and moving tribute: no sentimentality, just the life, staying alive in the memories of those who knew him.

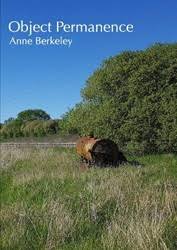

But back to the title poem, and ‘a two-thirty compulsion/ to see it in darkness’ — the ‘it’ being the bowser, described in the penultimate poem and shown in all its rusting glory on the cover. In “The Bowser” Berkeley places it in its landscape, part of her daily journey — ‘… solid in the corner near the bypass’ — where its unglamorous bulk decays in ‘uncropped pasture’. Why are some objects so compelling? Two years later she yields to the urge to trespass, ‘before sunrise’, to look closer, to feel it, to hear it when she slaps the side, to understand its earlier, useful years. These are apostrophised: the bowser has its own history

o grim beacon of loyalty and decay

of foundries in west midlands

young men trained in technical drawing

designing taps and gaskets

— representing more than just its own self. Like so much it becomes a ‘useless lump of metal/ too heavy too expensive/ to tow away’ and the poem ends without the expected full-stop: the decay will continue to seep out, as unending as Berkeley’s recall of its sturdy presence.

This is what “Object permanence’”, the final poem, shows, and her ‘compulsion’ to visit it in the small hours for the reality of it, despite the voice in her head — ‘… my dead mother’s warning/ don’t break your silly neck’. But the bowser’s presence in her past proves enough

I thought to go over

braving the thistles

prove by cold iron

its stubborn presence

then turned from the mystery

back towards home

neck still unbroken

no whit the wiser.

In writing these personal explorations of memory and its workings Berkeley leaves space for the reader to bring their own. This is a collection to read and re-read in its entirety, for its openness and clarity, for the way it values its past and the accumulated detail of ordinary life — if any life can just be ‘ordinary’. By enlarging the reader’s perceptions Berkeley’s poems affirm what poetry does best: staying attentive to the world in all its variety.

Feb 18 2026

London Grip Poetry Review – Anne Berkeley

Poetry Review – OBJECT PERMANENCE: D A Prince admires the perceptive insights that Anne Berkeley uses and explains in this collection of well-observed poems

Anne Berkeley

The Garlic Press, 2025

ISBN 978-1-0682630-0-2

80pp £12.00

Object Permanence is a perfect title for a collection centred on looking, watching, observing and remembering. If the concept is unfamiliar the collection’s Notes give a helpful definition as follows: ‘Object permanence’ is the understanding that objects can continue to exist even when we cannot perceive them. ‘La permanence de l’objet’ described by Jean Piaget is a milestone in child development.’

We, as adults, take this for granted: we can intuitively balance the visual memory of objects and places against their absence. This, however, is a learned skill which we don’t remember learning; so much is happening in those early years. Berkeley’s poems have now placed the idea in front of me, adding depth to the levels of attentiveness poets — and their readers — bring to poems.

The collection culminates in two poems that engage directly with this, with “Object permanence” as the final poem. It’s satisfying, as though the experiences described in earlier poems have finally been brought together, and in a way that reminds us how much we assume in regard to perception. But let’s start at the beginning, with the foundations. Berkeley does not write about theories of perception: she demonstrates them. Her poems are rooted in personal memory, with clarity, immediacy, and a sharpness of recall matched by the precision of her vocabulary and syntax. There’s a depth to the layering of memory in these poems that readers will recognise and share. Her poems have a wider range of reference than might appear on the surface. She’s able, too, to nod to her readings of other poets with a light touch only visible to the alert reader; again, ‘satisfying’ seems the appropriate description.

The past can be a list and while the opening poem, “Places I have slept”, is her list it also manages to draw in the reader, with that unspoken question: and what about you?

I slept in the top bunk, in the bottom bunk

in a tent, in another tent, in so many tents

in the peppering, sheeting rain

I slept on the bus

There’s no anecdotal context, nothing to explain the variety of places, and few adjectives — ‘peppering, sheeting rain’ is a rare example. Somehow those two adjectives expand, attaching their discomfort to other places, other beds. It sets the tone: this will be a plain-speaking, clear-sighted collection with a long view back down the years.

Childhood is fertile ground for recall. In the longest poem, “Gibraltar Point”, three pages in a child’s voice, Berkeley’s use of the present tense and minimal punctuation brings a seaside trip to life with a salty relish for the rhythms of a child’s speech patterns. It’s a headlong rush in just two sentences, the first rattling through the journey

Can you smell the sea he’ll ask and we all

say yes though we don’t know what the sea

smells like we think maybe it smells of fish

and chips and we finally get to the Skegness

is So Bracing fat sailor dainty on the big sign

long before houses then holiday shops with

shrimping nets and union jacks for sandcastles

but We’re Not There Yet we’re not stopping here

This equal placing of sounds and smells mirrors the way a child can hold them all in play simultaneously. The line breaks after ‘fish’, and then after ‘Skegness’, are teasing and fun. No italics for direct speech: again, this is a nod to a child’s way of recording. The Skegness railway poster (aka ‘The Jolly Fisherman’, commissioned in 1908) promoted Skegness for decades at railway stations, became the town’s mascot and now has its own Wikipedia page. The second sentence, the family car now parked (‘If there are no other cars/ it’s Good but we’re not there yet …’) rattles through the activities the carrying, running, squabbling, beach-combing, the hoping for ice-cream,: all the sensations of two children on a rare day by the sea. You can taste the salt.

Berkeley trusts her readers. “The away match” is, on first reading, a slight anecdote: on the second reading Berkeley’s lack of awareness of her social gaucheness is evident. It’s one of those rare poems where the reader is just slightly ahead of the poet; few can achieve this and I treasure those poems where it appears. By contrast “You only live twice” shows Berkeley’s late-in-the-day understanding of herself: on her Saturday shift in an antique shop she’s puzzled as a young man lingers, trying to decide on a purchase, the prices, engaging her in seemingly irrelevant conversation

Paul, it’s taken me until I’m practically antique

for the penny to drop:

what you were looking for,

how much it must have cost you.

Layers of time overlap via the most ordinary sights. In “Dirty old wheelbarrow” she watches delivery drivers unloading outside a hardware shop

Barrow after barrow trundles round the back

past washing lines, Atco mowers, Calor Gas,

to where my father’s shifting rubble

in the fifties. He’s just made a window

in the kitchen wall, to let in the morning

Who hasn’t been surprised at a similar linkage in their own memory? Among the connections to friends, named and un-named, is “The man who made poems: for R”. I recognised ‘R’ from the details given:

A man who knew things. Names of plants and knots. Works of Josephus and Scriabin.

Who made things: boxes, collages, casseroles, and salads …

[…]

Who replaced his rainbow jumper with a black one on the last day.

Anyone who remembers Roy Blackman, poet and co-editor of the poetry magazine Smiths Knoll, will remember that jumper, along with his innate modesty and kindness to poets. He died in 2002 and this is an eloquent and moving tribute: no sentimentality, just the life, staying alive in the memories of those who knew him.

But back to the title poem, and ‘a two-thirty compulsion/ to see it in darkness’ — the ‘it’ being the bowser, described in the penultimate poem and shown in all its rusting glory on the cover. In “The Bowser” Berkeley places it in its landscape, part of her daily journey — ‘… solid in the corner near the bypass’ — where its unglamorous bulk decays in ‘uncropped pasture’. Why are some objects so compelling? Two years later she yields to the urge to trespass, ‘before sunrise’, to look closer, to feel it, to hear it when she slaps the side, to understand its earlier, useful years. These are apostrophised: the bowser has its own history

o grim beacon of loyalty and decay

of foundries in west midlands

young men trained in technical drawing

designing taps and gaskets

— representing more than just its own self. Like so much it becomes a ‘useless lump of metal/ too heavy too expensive/ to tow away’ and the poem ends without the expected full-stop: the decay will continue to seep out, as unending as Berkeley’s recall of its sturdy presence.

This is what “Object permanence’”, the final poem, shows, and her ‘compulsion’ to visit it in the small hours for the reality of it, despite the voice in her head — ‘… my dead mother’s warning/ don’t break your silly neck’. But the bowser’s presence in her past proves enough

I thought to go over

braving the thistles

prove by cold iron

its stubborn presence

then turned from the mystery

back towards home

neck still unbroken

no whit the wiser.

In writing these personal explorations of memory and its workings Berkeley leaves space for the reader to bring their own. This is a collection to read and re-read in its entirety, for its openness and clarity, for the way it values its past and the accumulated detail of ordinary life — if any life can just be ‘ordinary’. By enlarging the reader’s perceptions Berkeley’s poems affirm what poetry does best: staying attentive to the world in all its variety.