Poetry review – THINGS WE LEAVE BEHIND and MEN OF THE SAME NAME: Ian Pople reviews new collections by Josephine Balmer and Evan Jones

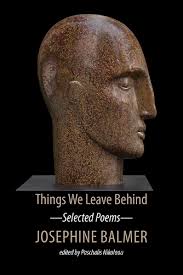

Things We Leave Behind: Selected Poems

Josephine Balmer

Edited with an introduction by Paschalis Nikolaou

Shearsman Books

ISBN 9781837380039

£14.95

Things We Leave Behind: Selected Poems

Josephine Balmer

Edited with an introduction by Paschalis Nikolaou

Shearsman Books

ISBN 9781837380039

£14.95

Men of the Same Name

Evan Jones

Carcanet Poetry

ISBN 9781800175136

£12.99

Men of the Same Name

Evan Jones

Carcanet Poetry

ISBN 9781800175136

£12.99

Josephine Balmer’s new selected poems Things We Leave Behind is edited with a lengthy introduction by Paschalis Nikolaou, who is Associate Professor of Literary Translation at the Ionian University, Greece. Nikolaou refers quite extensively to Balmer’s work as a translator of classical authors such as Sappho, Catullus and Ovid, and to Balmer’s own reflections on the process in her scholarly book, Piecing Together the Fragments: Translating Classical Verse, Creating Contemporary Poetry. And Nikolaou also places Balmer in the context of other contemporary poets working with classical authors including A.E. Stallings, Anne Carson, Seamus Heaney and Michael Longley. For Nikolaou, in particular, Balmer’s work aims to connect the past and present lives ‘with the same compassion and care shown towards the real people mentioned in or writing the documents from the Gallipoli campaign.’ Furthermore, Balmer has written poems connecting Gallipoli with ‘Ovid’s powerful laments about his own exile,’ in Tomis on the Black Sea; and Balmer had relatives killed in Gallipoli. Nikolaou also describes how Balmer’s sonnet sequence Letting Go, a sonnet sequence of elegies for Balmer’s mother ‘amalgamate versioned and quoted text by a sizable cast of classical authors.’

Evan Jones has also worked as a translator; his The Barbarians Arrive Today is a sizeable translation of poetry and prose by the twentieth century Egyptian/Greek poet, C.P. Cavafy and was a Times Literary Supplement book of the year in 2020. Simultaneously with this new Men of the Same Name, Jone has published a pamphlet of translations, Relations, from the Anstruther Press in Canada. This latter pamphlet contains translations from French, Charles Gros and Robert Desnos, and from other Greek poets, including Miltos Sachtouris and Kiki Dimoula.

Commentary on Men of the Same Name is, currently, limited to the back cover blurb which suggests that ‘What if, Jones asks, instead of using the ancient world as a metaphor for modern life, the poet uses modern life as a metaphor for the ancient world? Working in this way between allegory and reality, the book rethinks poetry’s changing relationships to politics and our historical moment.’ This latter comment does slightly throw the emphasis of both Men of the Same Name and Jones’ previous book Later Emperors. In both these books, there is clearly a focus on figures from the past whose records have survived for us; Jones is happy to acknowledge Gibbon’s Decline and Fall as a source for some of the poems in that earlier book. However, Jones, like Balmer, is keen to show the human side of the people he writes about. If this is working between ‘allegory and reality’ then one might wonder why so much is made of it. If poetry contains something aligned to a ‘poetic truth,’ then we might wonder why it is written at all. It’s worth noting that philosophers over the twentieth century have sometimes deferred to poetry’s ability to reach truths that philosophy can’t. And these truths are often truths about reality rather than, say, about the possibilities of abstracted politics or ethics.

As I’ve perhaps indicated, one major difference between Balmer and Jones is that Balmer is more liable to use classical situations to illustrate and work on themes from her personal life. Evans, on the other hand, deals with the personalities from Antiquity through to the Byzantine period in fictive terms. As mentioned above, Things We Leave Behind contains a number of poems which respond to the loss of Balmer’s ancestors in, in particular, the Gallipoli campaign. In “Among the Graves: Green Hill, Gallipoli,” Balmer describes walking through the eponymous graveyard. The poem ends,

Back by the gate, a lone stork takes flight,

marbled butterflies brush past, ‘half-mourners’,

insistent, impatient to shed black for white.

I wish now I’d spoken out, roll-called the names,

taken one small thing, at least, home to Gloucs:

rosemary sprig to dry, daisy or phlox to press

between calamitas, hurt and healed, consanatus.

In a note to this poem, Balmer comments that this particular graveyard is isolated and contains the mostly nameless graves of British soldiers killed at Gallipoli. Thus, the poem, itself, might be considered a way of speaking out and of roll-calling such names as occur. Impatient nature brushes past and takes flight, and the writer sees the opportunity to take, if also to preserve, for the writer too, passes on, returns to their home in Gloucs. This last abbreviation almost pulls the reader into the Britishness of it all, because, perhaps, only a Brit would have that shared frame of abbreviation. That shared frame is immediately followed by the, possibly, gendered hobby of pressing flowers, with the sense that this is something the family of that generation’s men would almost certainly have done. And then there is the move into the Latin. There is, here, a careful moving from the nature in and of the place to the narrator’s, clearly Balmer’s, voice in the need to bring out another domestic kind of remembrance. As such, that move into the Latin feels, perhaps, a little self-conscious, as if, somehow, the poem needed to prove its classical credentials.

“Among the Graves: Green Hill, Gallipoli” is one of a number of poems that are clearly personal to Balmer, and which she mixes with poems in the ‘voice’ of Ovid, using the name ‘Naso’ that Ovid calls himself in the Tristia or Sorrows poems that he wrote in exile. The poems selected in this section of the book come from Balmer’s book The Word for Sorrow. Balmer’s notes suggest that the ‘Naso’ poems are taken from edited parts of the Tristia poems. Thus, it is a little unclear whether these are translations or fictive dramatizations, with titles such as “Naso all at Sea”, “Naso writes his own epigraph” and “Naso sees Action”. This is the beginning of the last of those three poems;

Let me voice it: exile, soldier – said for respite not renown;

to stop the heart, free the thought by writing it down.

For my Muse travels with me, my friend, my betrayer,

and I am drawn to her like a besotted lover.

I, whose name was on all lips, the toast of Rome,

must now defend my life, what must be my home.

Now I live among wild tribes: Getae, Sauromate –

no longer safe but entrenched by wall and gate.

The poem goes on to describe the way the elderly Naso/Ovid must ‘strap on sword and shield’ and be prepared to go back into battle, ‘on a greying head of hair I buckle helmet.’

As we can see, Balmer has moved into a much more formal technique with the rhyming couplets. And there is a slight feel of strain in the writing; as if this poem really is a translation and there is a need to get Ovid’s content into something akin to an English rhythmic and rhyming equivalent. Line six in the extract I’ve quoted seems, to me, to exemplify this, where the phrase ‘my life’ would seem redundant and in the line only to fill out the metre.

Elsewhere, Balmer is usually more successful. The poem “Snow after Homer” begins;

Out of nowhere, it flurries thick and fast,

early winter, yet sharp as arrow shaft.

The wind calms. Grief is stilled. But it falls on

veiling the Forest hills, dark, distant Downs,

levelling fresh-ploughed farmland. By the church

it pales the priest’s black coat as he clears paths

in vain, ghosts the bonnet of skidded hearse;

There is still a slightly self-conscious feel to this: elisions of ‘as’ before ‘sharp’ in the second line and ‘the’ before ‘skidded hearse’ in the final line quoted; and the referent of the ‘it’ in the third line is ‘grief’ rather than the ‘snow’ that the poem suggests. However, the transposition of Homer’s world to the south of England is nicely manoeuvred into the evocation of ploughland and the priest outside the church.

Both Evan Jones’ previous volume Later Emperors and this new book Men of the Same Name, contain essentially fictive accounts of the lives of classical figures. In Later Emperors, Jones gave us longer pieces centred on the lives of two of the great figures of Byzantine culture, Michael Psellos, philosopher and historian, and Anna Komnene, the daughter and biographer of one of those emperors, and facilitator and preserver of commentaries on Aristotle and Plato. Men of the Same Name casts a wider net and includes, for example, “A Mirror for Princes On the Death of Prince Philip” ‘Mirrors for Princes’ were a common literary genre in Classical and Medieval times. As you might imagine, they were an attempt to speak truth to power, albeit on sometimes rather muted terms, when the sword or the rack might be the consequence of too much truth. Jones’ “A Mirror for Princes” depicts a Prince Philip within his Greek heritage. Jones’ poem begins with the line ‘And was the great kathreftist responsible?’ ‘Kathreftis’ is the Old Greek for ‘mirror’ which suggests that Philip was himself a kind of mirror. Thus the poem proclaims a range of ambiguities from the beginning. The first is that the poem is a way of holding Philip up to scrutiny, the second is, as mentioned above, that Philip holds ‘princeship’ up to scrutiny, and thirdly as though these two things mirrored each other in some wild mise en abyme. Alternatively, perhaps ‘the great kathreftist’ is someone else, a third person beyond the author or the Prince himself.

It is here, perhaps, that we get that sense of the cover blurb whereby Jones uses ‘modern life as a metaphor for the ancient world.’ Jones’ line in the poem that ‘I was young enough to remember / a different version,’ again throws up a series of ambiguities. How is it that Jones writes ‘young enough,’ when he would surely be ‘old enough’? Thus it is not just the mirror but also memory that becomes distorted in history. And the Prince Philip that emerges is that Greek Philip almost as a Byzantine figure who was ‘a charmer on the piano / and passably skilled in the woodwinds, …[who] gave voice to warlords, / sang the gathering of armies / and threats to the empire,’ whose songs ‘had earned him / as a young boy a goat with twins, /which he enjoyed milking.’ But then there is a turn, the poem’s narrator comments that ‘those charms are not / what he’s known for. He sang / his obscure songs, breathings, finger positions, / as a panacea. He would have liked, / he joked, during an especially inebriate / evening, to take the servants with him / at the end, as it used to be done.’ Certainly, the public persona of Prince Philip could often be one of a rather gaffe prone, Little Englander with a side order of wince-inducing cultural superiority. In private, one understands, Prince Philip was, indeed, a highly educated man who collected T.S Eliot and who impressed foreign visitors with his command of languages. Jones’ portrayal of the darker side of Prince Philip is an extraordinary version of the historical record. Jones is able to paint a picture of, if not quite the Byzantine figure, but someone deeply imbued with the practical trappings of that culture. Jones paints an exquisite picture of Prince Philip as someone both in and of history.

That note of turning history inside out to find it in the tactile and olfactory, and the charge of that inversion occurs throughout this often dazzling book. In “Stilpo, Late of Megara”, Jones writes as if the eponymous ‘hero,’ were walking around a contemporary Paris. Stilpo was a Greek philosopher of the second and third centuries BCE, whose philosophy is one whereby, and here I’m paraphrasing badly, each individual thing is a thing separate in itself; such that the Platonic ideal or universals are not contained in the individual. Jones’ paraphrase is contained in section four of the poem;

By myself, misfiring in my habits,

what I mean is: no having and holding

of beauty if beauty is everywhere.

We can’t live two lives at once,

feeding and clothing ourselves,

our children, pressed against

ambitions of, I guess, immortality.

Poetry thinks backward, forward,

drives everyone nuts or composes

them. Words themselves between

the leaf and the razorblade. Or neither.

No writings of Stilpo survive, other than in reports of his life by other philosophers and their reporting of some of Stilpo’s sayings. As Jones’ poem not only reports a Stilpo-like figure in a Paris with ‘postcard locales built of Lego and H&M.’ By recording ‘Stilpo’s’ observations with the words ‘nuts,’ the reader might imagine that the writer is using a Stilpo like figure to voice, to some extent, themselves. This is a poem that seems to declare certainty as fool’s gold. The poem tells us that beauty must be particularised. And it also suggests that poetry itself may offer little in the way of the sure and the absolute. The clear need is to feed and clothe ourselves and our children and not care about the abstract and the immortal. That charge is realised in the last two lines. There is, of course, further ambiguity underneath that; that Jones has chosen to write those lines and publish them in a book, which is in itself to make a claim to permanence. Thus, this is a book which in the act of writing ‘histories,’ knows that its truth claims are instantly undermined. Like Prince Philip, like Stilpo, Evan Jones can see that poetic truth has its own validities and that reaching towards that truth is its own ever valuable pursuit.

Jan 15 2026

London Grip Poetry Review – Josephine Balmer and Evan Jones

Poetry review – THINGS WE LEAVE BEHIND and MEN OF THE SAME NAME: Ian Pople reviews new collections by Josephine Balmer and Evan Jones

Josephine Balmer’s new selected poems Things We Leave Behind is edited with a lengthy introduction by Paschalis Nikolaou, who is Associate Professor of Literary Translation at the Ionian University, Greece. Nikolaou refers quite extensively to Balmer’s work as a translator of classical authors such as Sappho, Catullus and Ovid, and to Balmer’s own reflections on the process in her scholarly book, Piecing Together the Fragments: Translating Classical Verse, Creating Contemporary Poetry. And Nikolaou also places Balmer in the context of other contemporary poets working with classical authors including A.E. Stallings, Anne Carson, Seamus Heaney and Michael Longley. For Nikolaou, in particular, Balmer’s work aims to connect the past and present lives ‘with the same compassion and care shown towards the real people mentioned in or writing the documents from the Gallipoli campaign.’ Furthermore, Balmer has written poems connecting Gallipoli with ‘Ovid’s powerful laments about his own exile,’ in Tomis on the Black Sea; and Balmer had relatives killed in Gallipoli. Nikolaou also describes how Balmer’s sonnet sequence Letting Go, a sonnet sequence of elegies for Balmer’s mother ‘amalgamate versioned and quoted text by a sizable cast of classical authors.’

Evan Jones has also worked as a translator; his The Barbarians Arrive Today is a sizeable translation of poetry and prose by the twentieth century Egyptian/Greek poet, C.P. Cavafy and was a Times Literary Supplement book of the year in 2020. Simultaneously with this new Men of the Same Name, Jone has published a pamphlet of translations, Relations, from the Anstruther Press in Canada. This latter pamphlet contains translations from French, Charles Gros and Robert Desnos, and from other Greek poets, including Miltos Sachtouris and Kiki Dimoula.

Commentary on Men of the Same Name is, currently, limited to the back cover blurb which suggests that ‘What if, Jones asks, instead of using the ancient world as a metaphor for modern life, the poet uses modern life as a metaphor for the ancient world? Working in this way between allegory and reality, the book rethinks poetry’s changing relationships to politics and our historical moment.’ This latter comment does slightly throw the emphasis of both Men of the Same Name and Jones’ previous book Later Emperors. In both these books, there is clearly a focus on figures from the past whose records have survived for us; Jones is happy to acknowledge Gibbon’s Decline and Fall as a source for some of the poems in that earlier book. However, Jones, like Balmer, is keen to show the human side of the people he writes about. If this is working between ‘allegory and reality’ then one might wonder why so much is made of it. If poetry contains something aligned to a ‘poetic truth,’ then we might wonder why it is written at all. It’s worth noting that philosophers over the twentieth century have sometimes deferred to poetry’s ability to reach truths that philosophy can’t. And these truths are often truths about reality rather than, say, about the possibilities of abstracted politics or ethics.

As I’ve perhaps indicated, one major difference between Balmer and Jones is that Balmer is more liable to use classical situations to illustrate and work on themes from her personal life. Evans, on the other hand, deals with the personalities from Antiquity through to the Byzantine period in fictive terms. As mentioned above, Things We Leave Behind contains a number of poems which respond to the loss of Balmer’s ancestors in, in particular, the Gallipoli campaign. In “Among the Graves: Green Hill, Gallipoli,” Balmer describes walking through the eponymous graveyard. The poem ends,

In a note to this poem, Balmer comments that this particular graveyard is isolated and contains the mostly nameless graves of British soldiers killed at Gallipoli. Thus, the poem, itself, might be considered a way of speaking out and of roll-calling such names as occur. Impatient nature brushes past and takes flight, and the writer sees the opportunity to take, if also to preserve, for the writer too, passes on, returns to their home in Gloucs. This last abbreviation almost pulls the reader into the Britishness of it all, because, perhaps, only a Brit would have that shared frame of abbreviation. That shared frame is immediately followed by the, possibly, gendered hobby of pressing flowers, with the sense that this is something the family of that generation’s men would almost certainly have done. And then there is the move into the Latin. There is, here, a careful moving from the nature in and of the place to the narrator’s, clearly Balmer’s, voice in the need to bring out another domestic kind of remembrance. As such, that move into the Latin feels, perhaps, a little self-conscious, as if, somehow, the poem needed to prove its classical credentials.

“Among the Graves: Green Hill, Gallipoli” is one of a number of poems that are clearly personal to Balmer, and which she mixes with poems in the ‘voice’ of Ovid, using the name ‘Naso’ that Ovid calls himself in the Tristia or Sorrows poems that he wrote in exile. The poems selected in this section of the book come from Balmer’s book The Word for Sorrow. Balmer’s notes suggest that the ‘Naso’ poems are taken from edited parts of the Tristia poems. Thus, it is a little unclear whether these are translations or fictive dramatizations, with titles such as “Naso all at Sea”, “Naso writes his own epigraph” and “Naso sees Action”. This is the beginning of the last of those three poems;

The poem goes on to describe the way the elderly Naso/Ovid must ‘strap on sword and shield’ and be prepared to go back into battle, ‘on a greying head of hair I buckle helmet.’

As we can see, Balmer has moved into a much more formal technique with the rhyming couplets. And there is a slight feel of strain in the writing; as if this poem really is a translation and there is a need to get Ovid’s content into something akin to an English rhythmic and rhyming equivalent. Line six in the extract I’ve quoted seems, to me, to exemplify this, where the phrase ‘my life’ would seem redundant and in the line only to fill out the metre.

Elsewhere, Balmer is usually more successful. The poem “Snow after Homer” begins;

There is still a slightly self-conscious feel to this: elisions of ‘as’ before ‘sharp’ in the second line and ‘the’ before ‘skidded hearse’ in the final line quoted; and the referent of the ‘it’ in the third line is ‘grief’ rather than the ‘snow’ that the poem suggests. However, the transposition of Homer’s world to the south of England is nicely manoeuvred into the evocation of ploughland and the priest outside the church.

Both Evan Jones’ previous volume Later Emperors and this new book Men of the Same Name, contain essentially fictive accounts of the lives of classical figures. In Later Emperors, Jones gave us longer pieces centred on the lives of two of the great figures of Byzantine culture, Michael Psellos, philosopher and historian, and Anna Komnene, the daughter and biographer of one of those emperors, and facilitator and preserver of commentaries on Aristotle and Plato. Men of the Same Name casts a wider net and includes, for example, “A Mirror for Princes On the Death of Prince Philip” ‘Mirrors for Princes’ were a common literary genre in Classical and Medieval times. As you might imagine, they were an attempt to speak truth to power, albeit on sometimes rather muted terms, when the sword or the rack might be the consequence of too much truth. Jones’ “A Mirror for Princes” depicts a Prince Philip within his Greek heritage. Jones’ poem begins with the line ‘And was the great kathreftist responsible?’ ‘Kathreftis’ is the Old Greek for ‘mirror’ which suggests that Philip was himself a kind of mirror. Thus the poem proclaims a range of ambiguities from the beginning. The first is that the poem is a way of holding Philip up to scrutiny, the second is, as mentioned above, that Philip holds ‘princeship’ up to scrutiny, and thirdly as though these two things mirrored each other in some wild mise en abyme. Alternatively, perhaps ‘the great kathreftist’ is someone else, a third person beyond the author or the Prince himself.

It is here, perhaps, that we get that sense of the cover blurb whereby Jones uses ‘modern life as a metaphor for the ancient world.’ Jones’ line in the poem that ‘I was young enough to remember / a different version,’ again throws up a series of ambiguities. How is it that Jones writes ‘young enough,’ when he would surely be ‘old enough’? Thus it is not just the mirror but also memory that becomes distorted in history. And the Prince Philip that emerges is that Greek Philip almost as a Byzantine figure who was ‘a charmer on the piano / and passably skilled in the woodwinds, …[who] gave voice to warlords, / sang the gathering of armies / and threats to the empire,’ whose songs ‘had earned him / as a young boy a goat with twins, /which he enjoyed milking.’ But then there is a turn, the poem’s narrator comments that ‘those charms are not / what he’s known for. He sang / his obscure songs, breathings, finger positions, / as a panacea. He would have liked, / he joked, during an especially inebriate / evening, to take the servants with him / at the end, as it used to be done.’ Certainly, the public persona of Prince Philip could often be one of a rather gaffe prone, Little Englander with a side order of wince-inducing cultural superiority. In private, one understands, Prince Philip was, indeed, a highly educated man who collected T.S Eliot and who impressed foreign visitors with his command of languages. Jones’ portrayal of the darker side of Prince Philip is an extraordinary version of the historical record. Jones is able to paint a picture of, if not quite the Byzantine figure, but someone deeply imbued with the practical trappings of that culture. Jones paints an exquisite picture of Prince Philip as someone both in and of history.

That note of turning history inside out to find it in the tactile and olfactory, and the charge of that inversion occurs throughout this often dazzling book. In “Stilpo, Late of Megara”, Jones writes as if the eponymous ‘hero,’ were walking around a contemporary Paris. Stilpo was a Greek philosopher of the second and third centuries BCE, whose philosophy is one whereby, and here I’m paraphrasing badly, each individual thing is a thing separate in itself; such that the Platonic ideal or universals are not contained in the individual. Jones’ paraphrase is contained in section four of the poem;

No writings of Stilpo survive, other than in reports of his life by other philosophers and their reporting of some of Stilpo’s sayings. As Jones’ poem not only reports a Stilpo-like figure in a Paris with ‘postcard locales built of Lego and H&M.’ By recording ‘Stilpo’s’ observations with the words ‘nuts,’ the reader might imagine that the writer is using a Stilpo like figure to voice, to some extent, themselves. This is a poem that seems to declare certainty as fool’s gold. The poem tells us that beauty must be particularised. And it also suggests that poetry itself may offer little in the way of the sure and the absolute. The clear need is to feed and clothe ourselves and our children and not care about the abstract and the immortal. That charge is realised in the last two lines. There is, of course, further ambiguity underneath that; that Jones has chosen to write those lines and publish them in a book, which is in itself to make a claim to permanence. Thus, this is a book which in the act of writing ‘histories,’ knows that its truth claims are instantly undermined. Like Prince Philip, like Stilpo, Evan Jones can see that poetic truth has its own validities and that reaching towards that truth is its own ever valuable pursuit.