Poetry review – THE FAMILIAR: Alan Catlin gets to grips with a most original and unusual collection by Sarah Kain Gutowski

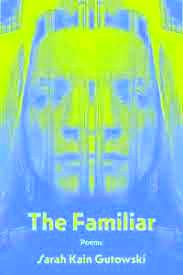

The Familiar

Sarah Kain Gutowski

Texas Review Press

ISBN: 978-1-68003-328-1

106 pp $21.95

The Familiar

Sarah Kain Gutowski

Texas Review Press

ISBN: 978-1-68003-328-1

106 pp $21.95

Sarah Kain Gutoski’s, The Familiar, is a complex, deep probing exploration of the many aspects of the self. The title illuminates one of the many complications the narrator is wrestling with: a familiar is defined, in opening remarks, as a friend or associate but also as an agent of the devil. Familiars in medieval times were supernatural spirits in league with Satan casting spells that caused bodily harm and sometimes death. Familiars were often household pets but could also be people. This overly vague definition of what exactly a familiar is, was often used as potential evidence by the Spanish Inquisition to condemn accused witches. It becomes painfully obvious that the familiar can also be a person existing within the self.

The Familiar is a one long poem broken into five distinct parts that directly relate to each other. Each section offers variations on the various selfs contained within the person who is the subject of the poem. This arrangement, this conjunction of parts, feels symphonic in nature: building, refining, and recapitulating until a fully developed theme is created.

The two prominent selfs we find in the early parts are: the ordinary self and the extraordinary self. The ordinary self can be defined as orderly, domestic, predictable, a mom who packs lunch, gets the kids off to school on time and the kind of wife who packs for her husband when he goes on business trips,

The consummate wife, my ordinary self helps my husband

Pack when he needs to leave on business, a checklist of items

In her back jeans pocket, her knack for rolling clothes

and using shoes for storage such a boon. When there’s time

She leaves notes folded inside his shirt pockets, or tucked

within the cufflinks box.

(from “The Rational Optimist”)

The extraordinary self refers to herself as a ‘burnt mess’. She isn’t good at packing her own stuff much less someone else’s. She isn’t practical, she’s basically a pessimist, lacks focus, is a dreamer with visions that are ‘operatic, symphonic and robust.’ She is, however, creative, spontaneous, in a glorious wild way, full of surprises, and bursts of inspiration. In a way, the ordinary self admires these attributes she does not have. The extraordinary self has,

So many busted enamel shards, rusted cables,

antique lamps collecting dust. The unused spools

of twine, boxes of glue, parts for builds abandoned.

Piles of books, face-down and dog-eared,

then forgotten. So much everything

and so much nothing-enthusiasm multiplied

and left to molder in humid air: A warehouse

for unrealized dreams.”

(from ”Time to Clean”)

The children rush to the ordinary self with their injuries, their wounds that require band aids and kisses. When the ordinary self tells the kids it is time to go somewhere and have fun, they know they will enjoy themselves. However the extraordinary self is someone the adults want to party with; it’ll be memorable, but probably not something you want the kids to experience at a young age.

These two opposing selfs do share one crucial element in their dichotomous relationship: they both share the husband (and presumably the children they produced.) Well before the first section is complete, we understand these disparate parts are of the same person and she is trying to reconcile these elements that exist within her person.

There are suggestions throughout the poems of kind of dissociative mental state. A healthy mental state should not be so clearly defined and at war with itself. The battle between these elements of her self – the working mother, and the artist who feels somewhat stifled by her responsibilities as a mother – intensifies as the poem progresses. At various points through the first four sections, the ordinary self is dominant and at others, the extraordinary one is. What saves the overall person, the poem, is that the tone throughout is arch, controlled, and assured despite the conflicts. A narrative perspective that projects such strength and self-knowledge presumes that the search to define the overall person’s nature is essentially a positive one.

The fifth section introduces the inevitable self,

My inevitable self is a bag of tricks. And yet, she’s not easy

to imagine – her shape flickers and shifts. One moment,

she’s a summation of stress easting multiplied over years,

her skin a roadmap where whiskey slicked and retrenched

its lines. The next moment, she melts into a cushion

for grandbabies, soft palaces to lean.

(from “Her Shape Flickers and Shifts”)

The timing of the arrival of the inevitable self comes just as the extraordinary and ordinary self have reached the end of their tether. The have reached irreconcilable limits, where drastic solutions have been vetted. These include a priest for an exorcism and a shrink to deal with the fragmented self that is a shattered mirror consisting of many broken pieces.

The inevitable self is more amorphous, hard to define as she does not fully exist yet. The two well outlined aspects of the self so vividly portrayed in the first three sections is morphing into something else that contains all these elements and, presumably more. The future may be uncertain but the very suggestion that there is one, that a new person, no matter how odd and eccentric, is still possible, leads the reader to have hope for the person in search of her true self. It might be a mess but, at last, it is something.

There are no easy reconciliations in The Familiar. What is certain to this reader is that The Familiar is a wonderous, enticing, thought provoking collection, that needs to be read slowly, multiple times, ideally alongside the poet’s previous collection, Fabulous Beast, which is a mythopoetic exploration of Femininity in ways that defy easy explanation. Read together or separately, it is obvious, in just two books, Gutowski has created a formidable body of work.

Feb 14 2024

London Grip Poetry Review – Sarah Kain Gutowski

Poetry review – THE FAMILIAR: Alan Catlin gets to grips with a most original and unusual collection by Sarah Kain Gutowski

Sarah Kain Gutoski’s, The Familiar, is a complex, deep probing exploration of the many aspects of the self. The title illuminates one of the many complications the narrator is wrestling with: a familiar is defined, in opening remarks, as a friend or associate but also as an agent of the devil. Familiars in medieval times were supernatural spirits in league with Satan casting spells that caused bodily harm and sometimes death. Familiars were often household pets but could also be people. This overly vague definition of what exactly a familiar is, was often used as potential evidence by the Spanish Inquisition to condemn accused witches. It becomes painfully obvious that the familiar can also be a person existing within the self.

The Familiar is a one long poem broken into five distinct parts that directly relate to each other. Each section offers variations on the various selfs contained within the person who is the subject of the poem. This arrangement, this conjunction of parts, feels symphonic in nature: building, refining, and recapitulating until a fully developed theme is created.

The two prominent selfs we find in the early parts are: the ordinary self and the extraordinary self. The ordinary self can be defined as orderly, domestic, predictable, a mom who packs lunch, gets the kids off to school on time and the kind of wife who packs for her husband when he goes on business trips,

The extraordinary self refers to herself as a ‘burnt mess’. She isn’t good at packing her own stuff much less someone else’s. She isn’t practical, she’s basically a pessimist, lacks focus, is a dreamer with visions that are ‘operatic, symphonic and robust.’ She is, however, creative, spontaneous, in a glorious wild way, full of surprises, and bursts of inspiration. In a way, the ordinary self admires these attributes she does not have. The extraordinary self has,

The children rush to the ordinary self with their injuries, their wounds that require band aids and kisses. When the ordinary self tells the kids it is time to go somewhere and have fun, they know they will enjoy themselves. However the extraordinary self is someone the adults want to party with; it’ll be memorable, but probably not something you want the kids to experience at a young age.

These two opposing selfs do share one crucial element in their dichotomous relationship: they both share the husband (and presumably the children they produced.) Well before the first section is complete, we understand these disparate parts are of the same person and she is trying to reconcile these elements that exist within her person.

There are suggestions throughout the poems of kind of dissociative mental state. A healthy mental state should not be so clearly defined and at war with itself. The battle between these elements of her self – the working mother, and the artist who feels somewhat stifled by her responsibilities as a mother – intensifies as the poem progresses. At various points through the first four sections, the ordinary self is dominant and at others, the extraordinary one is. What saves the overall person, the poem, is that the tone throughout is arch, controlled, and assured despite the conflicts. A narrative perspective that projects such strength and self-knowledge presumes that the search to define the overall person’s nature is essentially a positive one.

The fifth section introduces the inevitable self,

The timing of the arrival of the inevitable self comes just as the extraordinary and ordinary self have reached the end of their tether. The have reached irreconcilable limits, where drastic solutions have been vetted. These include a priest for an exorcism and a shrink to deal with the fragmented self that is a shattered mirror consisting of many broken pieces.

The inevitable self is more amorphous, hard to define as she does not fully exist yet. The two well outlined aspects of the self so vividly portrayed in the first three sections is morphing into something else that contains all these elements and, presumably more. The future may be uncertain but the very suggestion that there is one, that a new person, no matter how odd and eccentric, is still possible, leads the reader to have hope for the person in search of her true self. It might be a mess but, at last, it is something.

There are no easy reconciliations in The Familiar. What is certain to this reader is that The Familiar is a wonderous, enticing, thought provoking collection, that needs to be read slowly, multiple times, ideally alongside the poet’s previous collection, Fabulous Beast, which is a mythopoetic exploration of Femininity in ways that defy easy explanation. Read together or separately, it is obvious, in just two books, Gutowski has created a formidable body of work.