Poetry review – CLIMBING A BURNING ROPE: Charles Rammelkamp admires how John Paul Davis manages the trick of combining bleakness and hope

Climbing a Burning Rope

John Paul Davis

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2024

ISBN: 978-0-8229-6722-4

104 pages $18.00

Climbing a Burning Rope

John Paul Davis

University of Pittsburgh Press, 2024

ISBN: 978-0-8229-6722-4

104 pages $18.00

In a series of endearingly amusing “Bring Your [fill in the blank] to Work Day” poems (“Child,” “Horses,” “Everyone Who Was Laid Off,” “Your Selves from a Parallel Universe,” “an Ancient Mesopotamian Deity,” “a Ghost Car,” “the Number of Styrofoam Cups Americans Throw Away Every Second,” “a Forest Fire” and “Your Demons”), John Paul Davis gives voice to his spiritual dilemmas, his alarm about the state of our planet, and to the predicaments of his own quotidian workday routines, all major themes of this darkly comic, wise and wonderful collection of poems. As in the satirical movie Brazil, the narrator of these poems searches for love in a bureaucratic, technocratic society dominated by capitalist corporations. It’s an Orwellian world that he skewers mercilessly.

In “Bring Your Selves from a Parallel Universe to Work Day,” for instance, he cites several disturbing dystopias, including ‘The horrible president became a dictator dystopia’ (sound familiar?), ‘The church is still in charge dystopia,’ and ‘The David Bowie was never born dystopia.’ He elaborates about the various versions of himself in these dystopias:

The mes in dystopian universes don’t sleep. There’s a me who never

wrote poetry so never went to poetry readings

so never met anyone outside his lower middle class straight life

& still believes Jesus is coming back to blink

away true believers into some shimmery singalong

& that me is insufferable, chattering on, quoting the New Testament,

making it hard to concentrate on today’s emails.

The narrator has escaped from his own weird fundamentalist Christian upbringing in North Carolina to New York City (via Chicago, San Francisco, and elsewhere). He tells us in “Speaking in Tongues”:

Dad would close his eyes, breathe

out like he’d just set down a heavy suitcase

& whisper oh thank you father

even though nothing had happened yet.

Then this clattering, terrifying

nonsense would cascade out of him,

syllables for their own sake,

tumble of trills trampolining

off his tongue.

Later in the poem, seeking his father’s approval, the narrator mimics this behavior “because I knew / it’d make Dad proud of me.” He babbles on for about a minute, gibberish coming from his lips, an act of devotion – to his parent.

I waited for the Holy Spirit to reveal

to him my deception, expose

me, call me out, but instead

after I was sure I’d gone a full minute

I trailed off & Dad said oh thank you father

again & I felt his hand touch

the back of my neck. I thought

I’d feel loved by him….

But it only makes the chasm between them wider.

The narrator finds love amidst all the dehumanizing forces, and he values it, savors it. In the poem “Zipper,” he writes to his love:

when you were overseas

I’d call your voicemail

just to hear you

say your own name

which is my first favorite music.

Second is your keys

dancing in the deadbolt

when you get home from work…

“Incoming Video Call” is another poem honoring his love, juxtaposing it with the relentlessness of the corporations who make and sell the modern gadgets to which we are all addicted. These electronic devices are ultimately destroying the planet. The images they conjure aren’t “real,” but although he daydreams of a ‘life without unceasing screen-time,’ still he cherishes the illusion of his love’s image.

Just because I know every minute the mosaic

of light arranges itself in the shape of her face

brings us a few milliseconds closer to no polar ice caps

doesn’t mean I don’t scramble

to answer her call, all my oceans rising.

So much of this is reminiscent of Nineteenth Century romantic notions, just as Wordsworth laments the “getting and spending” to which we are all devoted in “The World Is Too Much With Us.” The Twentieth century Welsh poet, R.S. Thomas, likewise bemoaned “the Machine” in condemning the materialist/capitalist world.

So many of Davis’ poems include the word “life” in their titles – “Work Life,” “Come to Life,” “Half-Life,” “Proof of Life,” “Love Life,” “Animal Life,” “Mid-Life,” “Afterlife” – which provides the clue to his ultimate concern, what it means to be alive. Spontaneity is at the heart of it. He concludes “Love Life”:

You entered my life & made it a surprising thing

by being alive & yourself & near me,

& from now on, hallelujah,

many things will not

go according to plan.

God is mixed up in all of this, inevitably. And so are rabbits. The Afterlife? ‘My dad would insist / we were made to worship God / but that makes no sense,’ Davis writes in “Poem Raises New and Troubling Questions” (‘Heaven sounds super boring. At least if the Bible is true.’). This life? In “Out of Office Auto-Reply” he laments that he ‘sojourns in this empire / of spreadsheets and schedules / that would swallow my entire life if I so allowed.’ He prefers to ‘remember the sighs, the signs, / the sights, the scents, the sense / of my only and always true home.’ Which is his life with his love. In “This Is Our Religion,” he tells his love,

You tell me what makes you afraid.

I tell you why I’m sad. I lay my cheek on your clavicle.

You put the little rabbit of your hand

inside my shirt over my sacrum. In our theology

this is the same exact thing as praying.

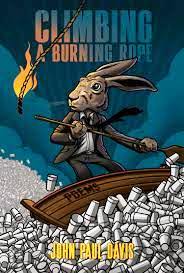

And there’s that rabbit! As well as featuring prominently in Clinton Reno’s cover art, rabbits appear in the first poem, “Wild Life” (‘Woke up full of rabbits.’), in “Transfiguration” (‘after dreaming all night I was a rabbit.’), “Animal Life,” and “Epigenetics” (‘I make wishes, touching wood / & think rabbits are messengers from an otherworld.’). They appear to be a symbol of the life force itself, the very life Davis puts such value on – as opposed to the machine. And this machine is the capitalist economy. Money. Davis’ cynicism about the obsession with money is prominent throughout, but especially in “Caressed by the Invisible Hand,” and in “Zugzwang,” a German word that means “forced to make a move.” In this poem, the narrator and his partner are contemplating buying a home, checking the real estate listings. The narrator considers “money,” which he distrusts (‘every dollar / is traceable to slavery, / the disintegrating glaciers, / murders by police / the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, / mass extinctions.’). And yet, they have to make a move, right?

& I imagine us scrambling

up a burning rope

trying to keep above the fire.

We can’t let go

& we can’t climb forever

This, too, is life. Climbing a Burning Rope is a delight to read for its good-humored take on what amounts to very bleak circumstances; though, like Pandora, he does find hope.

Jan 17 2024

London Grip Poetry Review – John Paul Davis

Poetry review – CLIMBING A BURNING ROPE: Charles Rammelkamp admires how John Paul Davis manages the trick of combining bleakness and hope

In a series of endearingly amusing “Bring Your [fill in the blank] to Work Day” poems (“Child,” “Horses,” “Everyone Who Was Laid Off,” “Your Selves from a Parallel Universe,” “an Ancient Mesopotamian Deity,” “a Ghost Car,” “the Number of Styrofoam Cups Americans Throw Away Every Second,” “a Forest Fire” and “Your Demons”), John Paul Davis gives voice to his spiritual dilemmas, his alarm about the state of our planet, and to the predicaments of his own quotidian workday routines, all major themes of this darkly comic, wise and wonderful collection of poems. As in the satirical movie Brazil, the narrator of these poems searches for love in a bureaucratic, technocratic society dominated by capitalist corporations. It’s an Orwellian world that he skewers mercilessly.

In “Bring Your Selves from a Parallel Universe to Work Day,” for instance, he cites several disturbing dystopias, including ‘The horrible president became a dictator dystopia’ (sound familiar?), ‘The church is still in charge dystopia,’ and ‘The David Bowie was never born dystopia.’ He elaborates about the various versions of himself in these dystopias:

The mes in dystopian universes don’t sleep. There’s a me who never wrote poetry so never went to poetry readings so never met anyone outside his lower middle class straight life & still believes Jesus is coming back to blink away true believers into some shimmery singalong & that me is insufferable, chattering on, quoting the New Testament, making it hard to concentrate on today’s emails.The narrator has escaped from his own weird fundamentalist Christian upbringing in North Carolina to New York City (via Chicago, San Francisco, and elsewhere). He tells us in “Speaking in Tongues”:

Dad would close his eyes, breathe out like he’d just set down a heavy suitcase & whisper oh thank you father even though nothing had happened yet. Then this clattering, terrifying nonsense would cascade out of him, syllables for their own sake, tumble of trills trampolining off his tongue.Later in the poem, seeking his father’s approval, the narrator mimics this behavior “because I knew / it’d make Dad proud of me.” He babbles on for about a minute, gibberish coming from his lips, an act of devotion – to his parent.

I waited for the Holy Spirit to reveal to him my deception, expose me, call me out, but instead after I was sure I’d gone a full minute I trailed off & Dad said oh thank you father again & I felt his hand touch the back of my neck. I thought I’d feel loved by him….But it only makes the chasm between them wider.

The narrator finds love amidst all the dehumanizing forces, and he values it, savors it. In the poem “Zipper,” he writes to his love:

when you were overseas I’d call your voicemail just to hear you say your own name which is my first favorite music. Second is your keys dancing in the deadbolt when you get home from work…“Incoming Video Call” is another poem honoring his love, juxtaposing it with the relentlessness of the corporations who make and sell the modern gadgets to which we are all addicted. These electronic devices are ultimately destroying the planet. The images they conjure aren’t “real,” but although he daydreams of a ‘life without unceasing screen-time,’ still he cherishes the illusion of his love’s image.

Just because I know every minute the mosaic of light arranges itself in the shape of her face brings us a few milliseconds closer to no polar ice caps doesn’t mean I don’t scramble to answer her call, all my oceans rising.So much of this is reminiscent of Nineteenth Century romantic notions, just as Wordsworth laments the “getting and spending” to which we are all devoted in “The World Is Too Much With Us.” The Twentieth century Welsh poet, R.S. Thomas, likewise bemoaned “the Machine” in condemning the materialist/capitalist world.

So many of Davis’ poems include the word “life” in their titles – “Work Life,” “Come to Life,” “Half-Life,” “Proof of Life,” “Love Life,” “Animal Life,” “Mid-Life,” “Afterlife” – which provides the clue to his ultimate concern, what it means to be alive. Spontaneity is at the heart of it. He concludes “Love Life”:

You entered my life & made it a surprising thing by being alive & yourself & near me, & from now on, hallelujah, many things will not go according to plan.God is mixed up in all of this, inevitably. And so are rabbits. The Afterlife? ‘My dad would insist / we were made to worship God / but that makes no sense,’ Davis writes in “Poem Raises New and Troubling Questions” (‘Heaven sounds super boring. At least if the Bible is true.’). This life? In “Out of Office Auto-Reply” he laments that he ‘sojourns in this empire / of spreadsheets and schedules / that would swallow my entire life if I so allowed.’ He prefers to ‘remember the sighs, the signs, / the sights, the scents, the sense / of my only and always true home.’ Which is his life with his love. In “This Is Our Religion,” he tells his love,

You tell me what makes you afraid. I tell you why I’m sad. I lay my cheek on your clavicle. You put the little rabbit of your hand inside my shirt over my sacrum. In our theology this is the same exact thing as praying.And there’s that rabbit! As well as featuring prominently in Clinton Reno’s cover art, rabbits appear in the first poem, “Wild Life” (‘Woke up full of rabbits.’), in “Transfiguration” (‘after dreaming all night I was a rabbit.’), “Animal Life,” and “Epigenetics” (‘I make wishes, touching wood / & think rabbits are messengers from an otherworld.’). They appear to be a symbol of the life force itself, the very life Davis puts such value on – as opposed to the machine. And this machine is the capitalist economy. Money. Davis’ cynicism about the obsession with money is prominent throughout, but especially in “Caressed by the Invisible Hand,” and in “Zugzwang,” a German word that means “forced to make a move.” In this poem, the narrator and his partner are contemplating buying a home, checking the real estate listings. The narrator considers “money,” which he distrusts (‘every dollar / is traceable to slavery, / the disintegrating glaciers, / murders by police / the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, / mass extinctions.’). And yet, they have to make a move, right?

& I imagine us scrambling up a burning rope trying to keep above the fire. We can’t let go & we can’t climb foreverThis, too, is life. Climbing a Burning Rope is a delight to read for its good-humored take on what amounts to very bleak circumstances; though, like Pandora, he does find hope.