Poetry review – BETWEEN A DROWNING MAN: Stuart Henson explores the territory defined by Martyn Crucefix’s deeply reflective poetry

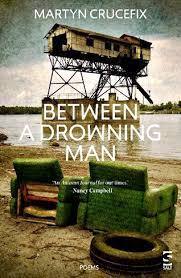

Between a Drowning Man

Martyn Crucefix

Salt

ISBN 978-1-78463-305-9

80pp £10.99

Between a Drowning Man

Martyn Crucefix

Salt

ISBN 978-1-78463-305-9

80pp £10.99

to talk

about difference

…

with its sudden

sometimes shocking riches

Not easy, but that’s the task that Martyn Crucefix wants to tackle in his latest offering, from Salt Publishing. And ‘difference’, amongst other things, means difference of opinion, experience, intention… Crucefix has always been one of the most interesting and experimental of poets working in what’s sometimes called the mainstream, and in this book he offers two sequences that push at the boundaries of language to explore

how the world’s complexity

makes us dread it more

makes us other everything

and everyone we meet

The last fourteen pages of the collection are a reprint of the subtle and rather lovely O, at the Edge of the Gorge that I wrote about for London Grip in January 2018. The first—and by far the longer—sequence, entitled ‘Works and Days’, draws on the combined sources, or resources, of Hesiod and of the 10th-12th Century Indian texts known as vacanna. The Hesiod supplies not only the title but also a context in which to frame the antagonisms between brother and brother, the differences eloquently expressed by the gap in the first line quoted above. Crucefix intends the poems to reflect what he deems ‘a progressively more disunited kingdom’, riven by Brexit, identity politics and factionalism. In this regard, it’s interesting that Hesiod is also credited with being the first to recount the Pandora legend, since hope is, perhaps, the one thing that Crucefix feels we have left in a world where her jar or box of evils is so fully open.

The influence of the vacanna (translated into English for the Penguin Classics by A.K. Ramanujan in 1973) is, if anything, even more evident in his approach in Part One of Between a Drowning Man. The most obvious trope is the repetition of a single powerfully significant line at the end of each or almost all of the poems. In the case of the earliest poet, Basavanna, the repeated line uses a way of addressing the god Shiva himself—as the ‘lord of the meeting of rivers’. Crucefix’s refrain-line is the more prosaic but also more usefully open-ended ‘all the bridges are down’. (He eschews the use of capitals and punctuation throughout) The phrase becomes a standing metaphor for breakdown in communication—between child and parent, rich and poor, soul and body… It’s a powerful and versatile image, derived from the experience of being affected by the extensive flood-damage in the Lake District in the spring of 2016. For an explanation of this, and an interesting discussion of the poem “you are not in search of”, it’s well worth visiting the Mouthful of Air podcast with Mark McGuinness here .

In the majority of the poems it’s simply (or not so simply) the lineation, repetition and observational detachment of the vaccana poets that’s to the fore. We are firmly in the contemporary world of Twitterstorm, Google Map, Uber and Wi-fi—yet somehow at an angle to it. The irony of the so-called togetherness achieved by the use of social media is amusingly (and rather tragically) presented in “watch the child”, where a toddler with a ‘bright picture book’ is gazing into mid-air.

her several gestures of several kinds

it’s as if she is doing

the different voices herself

now gazing up into mid-air

her mother at her cooling latte

at her macchiato

at her cooling skinny medium cappuccino

at her americano her mother

at her frappuccino rising to room temperature

her mother’s ears wired casually

with two scarlet buds

for minutes she gazes into the middle distance

vanishing red wires snaking into her lap

The economy of Crucefix’s models is evident in his presentation of the muttering child, the distracted mother, who’s not one but many, in the use of the telling adverb ‘casually’ and the careful choice and placement of that key-word ‘vanishing’. It all coheres so cleverly that the concluding

all the bridges are down

seems almost redundant.

In some cases, when he works more directly from a Kannada poem, he may use a phrase taken from the original, such as ‘you can make them talk’ (“I have explained you can make them talk – after Basavanna”) or indeed whole ideas. An example of the latter would be the way in which Crucefix transforms Basavanna’s ‘You can make them talk / if they’re struck / by an evil planet.’ into

there will be days you can urge them to talk

when they are caught

a glancing blow at the crossing

Basavanna’s ‘evil planet’, Ramanujan notes, is a metaphor for misfortune in general, so the sudden shock of the pedestrian struck by a vehicle is both specific and generally appropriate. Crucefix is also prepared to expand and ‘riff’, as they say, on the foundational idea:

you can persuade them to talk

by ducking their heads under water

sometimes you can lure them into speech

on the pillow afterwards

drawing a trail of hair from their forehead

These images have no counterpart in Basavanna, but the juxtaposition of violence and tenderness in the additional stanzas is more than germane to both poets’ themes. In the end Crucefix draws the poems together with a reference to a key idea from the original.

but try as you might you can’t make them talk

when they’re struck dumb by riches

It’s a thought-provoking notion: wealth as an inhibiting factor in human communication. And most of us in the UK are wealthy, if only in the terms he sets out in “Invitation”:

say what scares you

(nothing but the mite you have

the dread of its loss)

So there’s an ambiguity in the life-style he presents in “how you order”. Like the original vacanna the tone is philosophical rather than judgmental. At first you might feel there’s an ironical, if not satirical intent:

how you order then sip your flat white with care

or diesel with care or cling film

or eat responsibly sourced seafood with care

red meat or bottled carbonated water

But halfway through the poem your doubts begin to creep in:

then insist on being used by the language with care

with care conversing with friends

when touching friends and your extended family

with care your actions

have a care and your reactions with care

with a passionate care where possible your politics

The reference to ‘being used by the language’ suggests that maybe the poet himself is not exempt from his own scrutiny. Maybe we’re all caught up in a network of social and personal connections that tests our resolve to be good, to be conscientious. That care is no simple thing in a world where all the bridges are down.

When material and technological well-being takes over from spiritual contemplation the challenge becomes even more complex. In Basavanna’s world, possessions could all too easily become obsessions. ‘The pot is a god. The winnowing / fan is a god. The stone in the / street is a god. The comb is a / god. The bowstring is also a / god…’ (poem 563) It helps, I think, to know the model when it comes to calibrating Crucefix’s version.

the data set the next level my mobile phone

with its allure of a liquid retina screen

the purity of product the window display

all these are gods the parking assist the speed

of delivery the hemp tote bag are also gods…

His list of the worshipful/bewildering aspects of contemporary life is longer than Basavanna’s, but he shares the conclusion that ‘O there are so many gods // hence so little space left to set my feet’.

Among the consequences of ageing (Crucefix is now in his late sixties) is a growing awareness of mortality—and the illusory nature of the material world. There are a number of poems in Between a Drowning Man that look unflinchingly at his own fragile humanity, including the painfully physical “before the doctor asks to examine” and the vividly colourful “after so many years”. Poems, too, that reflect on his parents’ frailty and the pain of their loss, or his continuing genetic presence in the lives of his children. Yet the overall mood is not of gloom, but wonder—almost puzzlement at times. The clarity of the language begets a kind of luminosity, as in “when” which begins engagingly

when

like a falling flower-print cotton dress

has dropped its round spoor

in the breathy silence on the bedroom floor

and ends:

when

like the salt-wetness breaking bounds in my eyes

in an original participation

I lean over and touch what is there

my hand passing through what I thought was there all along

when

in an instant it is clear all the bridges are down

how can I speak to anybody about that

How, indeed? The only way, perhaps, is through what Crucefix identifies as ‘the steady and constant labouring of the wounded spirit’ which strives to make something a bit like a bridge from the intractable stones we call words.

Nov 23 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Martyn Crucefix

Poetry review – BETWEEN A DROWNING MAN: Stuart Henson explores the territory defined by Martyn Crucefix’s deeply reflective poetry

to talk about difference … with its sudden sometimes shocking richesNot easy, but that’s the task that Martyn Crucefix wants to tackle in his latest offering, from Salt Publishing. And ‘difference’, amongst other things, means difference of opinion, experience, intention… Crucefix has always been one of the most interesting and experimental of poets working in what’s sometimes called the mainstream, and in this book he offers two sequences that push at the boundaries of language to explore

how the world’s complexity makes us dread it more makes us other everything and everyone we meetThe last fourteen pages of the collection are a reprint of the subtle and rather lovely O, at the Edge of the Gorge that I wrote about for London Grip in January 2018. The first—and by far the longer—sequence, entitled ‘Works and Days’, draws on the combined sources, or resources, of Hesiod and of the 10th-12th Century Indian texts known as vacanna. The Hesiod supplies not only the title but also a context in which to frame the antagonisms between brother and brother, the differences eloquently expressed by the gap in the first line quoted above. Crucefix intends the poems to reflect what he deems ‘a progressively more disunited kingdom’, riven by Brexit, identity politics and factionalism. In this regard, it’s interesting that Hesiod is also credited with being the first to recount the Pandora legend, since hope is, perhaps, the one thing that Crucefix feels we have left in a world where her jar or box of evils is so fully open.

The influence of the vacanna (translated into English for the Penguin Classics by A.K. Ramanujan in 1973) is, if anything, even more evident in his approach in Part One of Between a Drowning Man. The most obvious trope is the repetition of a single powerfully significant line at the end of each or almost all of the poems. In the case of the earliest poet, Basavanna, the repeated line uses a way of addressing the god Shiva himself—as the ‘lord of the meeting of rivers’. Crucefix’s refrain-line is the more prosaic but also more usefully open-ended ‘all the bridges are down’. (He eschews the use of capitals and punctuation throughout) The phrase becomes a standing metaphor for breakdown in communication—between child and parent, rich and poor, soul and body… It’s a powerful and versatile image, derived from the experience of being affected by the extensive flood-damage in the Lake District in the spring of 2016. For an explanation of this, and an interesting discussion of the poem “you are not in search of”, it’s well worth visiting the Mouthful of Air podcast with Mark McGuinness here .

In the majority of the poems it’s simply (or not so simply) the lineation, repetition and observational detachment of the vaccana poets that’s to the fore. We are firmly in the contemporary world of Twitterstorm, Google Map, Uber and Wi-fi—yet somehow at an angle to it. The irony of the so-called togetherness achieved by the use of social media is amusingly (and rather tragically) presented in “watch the child”, where a toddler with a ‘bright picture book’ is gazing into mid-air.

her several gestures of several kinds it’s as if she is doing the different voices herself now gazing up into mid-air her mother at her cooling latte at her macchiato at her cooling skinny medium cappuccino at her americano her mother at her frappuccino rising to room temperature her mother’s ears wired casually with two scarlet buds for minutes she gazes into the middle distance vanishing red wires snaking into her lapThe economy of Crucefix’s models is evident in his presentation of the muttering child, the distracted mother, who’s not one but many, in the use of the telling adverb ‘casually’ and the careful choice and placement of that key-word ‘vanishing’. It all coheres so cleverly that the concluding

seems almost redundant.

In some cases, when he works more directly from a Kannada poem, he may use a phrase taken from the original, such as ‘you can make them talk’ (“I have explained you can make them talk – after Basavanna”) or indeed whole ideas. An example of the latter would be the way in which Crucefix transforms Basavanna’s ‘You can make them talk / if they’re struck / by an evil planet.’ into

there will be days you can urge them to talk when they are caught a glancing blow at the crossingBasavanna’s ‘evil planet’, Ramanujan notes, is a metaphor for misfortune in general, so the sudden shock of the pedestrian struck by a vehicle is both specific and generally appropriate. Crucefix is also prepared to expand and ‘riff’, as they say, on the foundational idea:

you can persuade them to talk by ducking their heads under water sometimes you can lure them into speech on the pillow afterwards drawing a trail of hair from their foreheadThese images have no counterpart in Basavanna, but the juxtaposition of violence and tenderness in the additional stanzas is more than germane to both poets’ themes. In the end Crucefix draws the poems together with a reference to a key idea from the original.

but try as you might you can’t make them talk when they’re struck dumb by richesIt’s a thought-provoking notion: wealth as an inhibiting factor in human communication. And most of us in the UK are wealthy, if only in the terms he sets out in “Invitation”:

So there’s an ambiguity in the life-style he presents in “how you order”. Like the original vacanna the tone is philosophical rather than judgmental. At first you might feel there’s an ironical, if not satirical intent:

But halfway through the poem your doubts begin to creep in:

The reference to ‘being used by the language’ suggests that maybe the poet himself is not exempt from his own scrutiny. Maybe we’re all caught up in a network of social and personal connections that tests our resolve to be good, to be conscientious. That care is no simple thing in a world where all the bridges are down.

When material and technological well-being takes over from spiritual contemplation the challenge becomes even more complex. In Basavanna’s world, possessions could all too easily become obsessions. ‘The pot is a god. The winnowing / fan is a god. The stone in the / street is a god. The comb is a / god. The bowstring is also a / god…’ (poem 563) It helps, I think, to know the model when it comes to calibrating Crucefix’s version.

the data set the next level my mobile phone with its allure of a liquid retina screen the purity of product the window display all these are gods the parking assist the speed of delivery the hemp tote bag are also gods…His list of the worshipful/bewildering aspects of contemporary life is longer than Basavanna’s, but he shares the conclusion that ‘O there are so many gods // hence so little space left to set my feet’.

Among the consequences of ageing (Crucefix is now in his late sixties) is a growing awareness of mortality—and the illusory nature of the material world. There are a number of poems in Between a Drowning Man that look unflinchingly at his own fragile humanity, including the painfully physical “before the doctor asks to examine” and the vividly colourful “after so many years”. Poems, too, that reflect on his parents’ frailty and the pain of their loss, or his continuing genetic presence in the lives of his children. Yet the overall mood is not of gloom, but wonder—almost puzzlement at times. The clarity of the language begets a kind of luminosity, as in “when” which begins engagingly

when like a falling flower-print cotton dress has dropped its round spoor in the breathy silence on the bedroom floorand ends:

when like the salt-wetness breaking bounds in my eyes in an original participation I lean over and touch what is there my hand passing through what I thought was there all along when in an instant it is clear all the bridges are down how can I speak to anybody about thatHow, indeed? The only way, perhaps, is through what Crucefix identifies as ‘the steady and constant labouring of the wounded spirit’ which strives to make something a bit like a bridge from the intractable stones we call words.