Oct 6 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Sean O’Brien

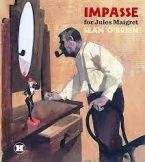

Poetry review – IMPASSE FOR JULES MAIGRET: Edmund Prestwich enjoys Sean O’Brien’s atmospheric evocation of mid-twentieth century Paris

Impasse for Jules Maigret Sean O’Brien Hercules Editions ISBN 978-1-7393740-0-6 £10

The Hercules Editions booklets I’ve seen so far are like little jewel boxes combining poetry, visual art and essays that come at the poems’ theme from the angle of prose reflection. I’ll say something about the visual aspect of Sean O’Brien’s Impasse for Jules Maigret later. First the poems.

Sean O’Brien is a superb metrist. There’s a keen, physical pleasure in the assurance with which he handles established metres and the deftness with which he twists them to original ends, often seamlessly shifting between different metrical pulses within a single poem or line.

In terms of the contents of his writing, he’s a master of grittily physical imagery that immerses the reader in what feels like immediate visual, tactile, auditory reality. The definition given to the words by their metre and rhythm heightens their impact and therefore the reader’s sense of absorption into the world they evoke. However, the power of these poems is not their physical evocativeness in itself, it’s in the way suggestions of a grittily solid world are constantly intercut with or dissolve into such a world’s opposite, lending hallucinatory vividness to impressions of dreamlike unreality, of things both pressing on you and eluding your grasp. And as in dreams, everything seems to hold an almost-human but at the same time disturbingly alien life. This is from ‘The Sacred Heart’, which follows old canals:

You find the locks almost intact, the rusted gear still turning, cottages half in the woods suspicious still, their gaze averted and omniscient.

This from ‘Oysters’:

That night you hoped for oysters too – but it’s neap tide, when none can be gathered: clinging to their sunken stakes they wait for death, unblinking in the salty dark.

Such images, teasing our imaginations with their arresting, arrested vividness, seem fraught with meanings in excess of their context. This is another way in which they’re dreamlike. They invite us to move around them, finding subtly shifting glints of suggestion and implication within them; for example, the way ‘unblinking’ hints at a kind of silent heroism in the endurance of the suppressed and vulnerable human lives suggested throughout the booklet and called to mind by the oysters.

As its title suggests, Impasse for Jules Maigret is a homage to Simenon’s detective hero. I think all the material detail of the booklet is drawn from novels he appears in. O’Brien’s concern isn’t with their plots, though. In his ‘Afterword’, he explicitly evokes the analogy with dream, saying, ‘I wanted to identify something in the Simenon paysage which nagged at and haunted me, beginning with a canal in the coalfields near the Belgian border, and moving on to a bar in what Auden called “a decaying port” on the Channel coast.’ He describes his procedure as ‘entering Maigret’s world randomly – an experience analogous to dreamlife, where certain motifs … recur without ever quite abolishing the mystery that animates them’ and he calls the poems ‘a reverie on [Simenon’s] turf.’

A dreamer’s mind transforms the stimuli that enter his dreams. What O’Brien does with the material from Simenon is shaped by his own conscious and unconscious preoccupations, creating new meanings at every step. Wherever we turn we see more generalised resonances being distilled from the given particulars. So in the beginning of ‘Garagistes’, almost metaphysical suggestions emerge from phrases which presumably had a more pragmatic import in the original novel:

In this paradise of garagistes, everything is far away. It will be night. It will be raining. So the world is not accessible from here, my friends. Only killers and detectives are abroad, apart, that is, from lovers’ corpses sprawling in the ditches, with their pitiable candour anguished in the fleeting moonlight.

In the novels, on a simple plot level, Maigret solves the cases he undertakes. O’Brien’s interest is in what underlies these plots, something that couldn’t be solved in Maigret’s world and can’t in ours; to put it crudely, the mismatch between human nature, needs or desires and the world they find themselves in. So, befitting the booklet’s title of Impasse, it’s pervaded by images of frustration, emptiness, deadlock and dead ends in a world of dereliction and decay. There’s no escape, it seems. On one level, then, it’s a chilling distillation of alienation, depression and despair. But reading it is far from depressing. The grimness of its material is transfigured by O’Brien’s expressive power, the articulate energy of his writing, the vitality of his rhythms and images, his wit, his compassion and the vitally changing, multifaceted responses he invites. In the second half of ‘The Sacred Heart’ he writes

Someone should corroborate these facts but everyone is either sleeping or deceased. Instead there is a room all corners, with a yellow smell of want and poor digestion, plus a glass of glaring teeth beside the Sacred Heart, and all of this belongs to France, the heart of yellow-grey long dead and beating still.

What could be more depressing than the hard, angular poverty of the scene? And yet there’s a transfiguring vitality in the way the poetry mediates it. At the start of this quotation, phrases move in a quick, taut way, momentarily restrained by the line endings only to spring forward from them, as if propelled by elastic. The last three lines slow and settle in a graceful docking manoeuvre that ends in reflective stillness. The depiction of deprivation shimmers with mordant wit in phrases like ‘want and poor digestion’ or ‘glaring teeth’. In the imagery of dream we can find ourselves thinking of the teeth as glaring because they have no food to bite. And reflections start unspooling as soon as we pause in our reading. To take just one example, the last line looks in opposite directions – towards a despairing sense that all the ghastliness is still unkillably there, or towards a sense of France’s resilience under everything negative that life can throw at it. The sensitivity towards language that allows individual words to carry such different implications makes a word like ‘want’ connect with streams of thought beyond its immediate main sense of material poverty; in a wider sense, it links with the idea of desire that runs through the whole sequence, from the last line of the first poem – ‘the facts alone cannot explain desire’ – to the last poem, ‘Fin’, imagining ‘The day when crime shall be no more, / when desire and loss are spent like lovers’.

The distinctive feature of the Hercules Editions booklets, apart from their neat, almost square 125mm x 140mm format, is their complementing of poetry with prose reflection and visual image. Here, as well as O’Brien’s ‘Afterword’ there’s an elegant short essay on Simenon by Patrick McGuiness. And the visual images accompanying this booklet are particularly well chosen and reproduced. Several, in different graphic styles and modes, are illustrations, advertisements or stills relating directly to the Maigret books or films. Most beautiful, for me, though, was a finely reproduced photograph of a cabaret dressing room. One of the pretty young women in it looks up with a bold, hopeful expression, another, touching up her make-up, looks at her mirror with a quiet smile. The whole image speaks of health, purpose and freshness and leaves us to make what we will of its placing in context. The format of the booklet brings its texts and pictures together in a non-confrontational way whose very smoothness allows them to counterpoint as well as amplifying each other.

Edmund Prestwich» Blog Archive » Sean O’Brien, Impasse for Jules Maigret – review

06/10/2023 @ 15:25

[…] on the title Impasse for Jules Maigret for a link to my review, with thanks to Michael Bartholomew-Biggs and the London Grip where it […]