Poetry review – HARD DRIVE: James Roderick Burns reviews a substantial collection by Paul Stephenson that is both poignant and very personal

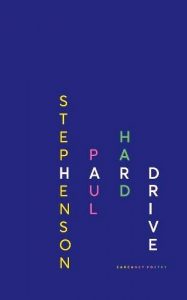

Hard Drive

Paul Stephenson

Carcanet, 2023

ISBN 9 781800 173279

£12.99

Hard Drive

Paul Stephenson

Carcanet, 2023

ISBN 9 781800 173279

£12.99

I grew up equating the idea of a ‘poetry collection’ with the fabled slim volume: classics such as Whitsun Weddings, High Windows; authors like Sylvia Plath, Thom Gunn, Seamus Heaney. With a spine so skinny it barely encompassed the title and the poet’s name, perhaps a tactile, pebbly cover and multiple blank leaves at the back, still redolent of the printer’s shop. Perhaps it’s just my age, but I still associate the two, even when poetry has hugely magnified its reach and spread electronic tentacles around the globe.

Hard Drive is therefore a slight problem, in this context: with six substantial sections, a massive variety of forms and styles, and a narrative through-line tracing the processes of a partner’s tragic, early death – complete with every feeling, stage and bureaucratic obstacle – it weighs in at a hefty 126 pages, almost three times the length of a traditional slim volume.

This isn’t a conceptual problem: the arc of the book, its overall and sectional organisation, as well as emotional heft, make perfect sense; the issue is perhaps one of readability, an understandable need to fill in gaps of understanding that a shorter collection might leave to the reader, and the reader in turn might enjoy interpolating.

In section II, ‘Officialdom’, for instance, we find a lean, effective interrogation of the numbing bureaucratese surrounding the administration of death. (A disclaimer: I was involved with registration and the certification of death for more than a decade, so have an active interest in the management of language, and in particular, official tone.) After noting the dry relational phrases ordinarily employed (concerning, regarding, relating to) Stephenson is surprised by an unexpected tenderness in one official communication:

This case file is touching

the death of

and like a forefinger

on the lips,

I am touched

by its usage, how

it seems to soften

what is so hard.

It is a brief but surprising poem, touching in its spare observations, which allow a sympathetic reader to muse on the usual, brute reality of administrative writing – harsh, bald even, and rarely if ever moving. Yet in the same section there follow numerous additional poems expanding on this theme. ‘A Prayer for Death Admin,’ for instance, enumerates in list fashion all the numbing points of engagement with officials and customer representatives, yet somehow loses impact in the wake of the earlier poem. Some judicious editing for length and cumulative effect might have helped, here – as Larkin noted in ‘Dockery and Son’, “Why did he think adding meant increase?/To me it was dilution.”

A later poem, “The Hymn of Him’, is a marvel of innovation and grace, practically reinventing the list-poem on a single page:

The lip of him, the map of him, the mop,

the nap of him, the nip of him, the pep;

the pip of him, the pup of him, the quip,

the rap of him, the rep of him, the rip.

It revels in personal, human diversity, not ducking anything less flattering (“the fop of him, the gap of him”) while celebrating a partner’s splendid variety, and mourning his loss, especially in a quiet but devastating conclusion:

The ship of him, the shop of him, the sh’up,

the chap of him, the chip of him, the chop.

The last suggestion – of a splintering, a potential coming apart of life, even of coherent memories – resonates through the whole collection. But the poet returns over and again to new versions of the list (‘All the Never You Can Carry,’ ‘Relationship as Covered Reservoir,’ and perhaps most pointedly ‘Your Brain’) giving the reader a sense of retreading ground (albeit inventively) and perhaps diminishing returns.

To return to the idea of a slim volume versus a thicker one, it is easy to object that exploring, memorialising and celebrating a whole life – even one cut short – requires as much time and space as it requires, regardless of the demands this may place on a reader. There is some justice to this argument. Yet, perversely, the practice of assembling a collection has its own implacable logic. What might work in, say, a published journal or longer non-fiction work – accumulation of detail, the gradual building of a comprehensive portrait – can work against the impact of a poetry collection.

As the first line of ‘Hand Puppets’ suggests, “Whenever I stop and think of you at your youest”, we best perceive the terrible processes of a death, its multitudinous adjustments, through well-chosen highlights, lowlights, rather than a piling-up of the same. Stephenson further notes (with a degree of ambivalence) in the title poem that the collection of moments sometimes brings its own pressures, and perhaps distortions. Overall, Stephenson stops short of the latter possibility and his lines resonate with a sense of what might have been:

I will get a man to locate our life

to retrieve our life our love

and transfer it so I can relive it

some day our life of years

all the days sitting there

unlooked at us collected

Oct 5 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Paul Stephenson

Poetry review – HARD DRIVE: James Roderick Burns reviews a substantial collection by Paul Stephenson that is both poignant and very personal

I grew up equating the idea of a ‘poetry collection’ with the fabled slim volume: classics such as Whitsun Weddings, High Windows; authors like Sylvia Plath, Thom Gunn, Seamus Heaney. With a spine so skinny it barely encompassed the title and the poet’s name, perhaps a tactile, pebbly cover and multiple blank leaves at the back, still redolent of the printer’s shop. Perhaps it’s just my age, but I still associate the two, even when poetry has hugely magnified its reach and spread electronic tentacles around the globe.

Hard Drive is therefore a slight problem, in this context: with six substantial sections, a massive variety of forms and styles, and a narrative through-line tracing the processes of a partner’s tragic, early death – complete with every feeling, stage and bureaucratic obstacle – it weighs in at a hefty 126 pages, almost three times the length of a traditional slim volume.

This isn’t a conceptual problem: the arc of the book, its overall and sectional organisation, as well as emotional heft, make perfect sense; the issue is perhaps one of readability, an understandable need to fill in gaps of understanding that a shorter collection might leave to the reader, and the reader in turn might enjoy interpolating.

In section II, ‘Officialdom’, for instance, we find a lean, effective interrogation of the numbing bureaucratese surrounding the administration of death. (A disclaimer: I was involved with registration and the certification of death for more than a decade, so have an active interest in the management of language, and in particular, official tone.) After noting the dry relational phrases ordinarily employed (concerning, regarding, relating to) Stephenson is surprised by an unexpected tenderness in one official communication:

It is a brief but surprising poem, touching in its spare observations, which allow a sympathetic reader to muse on the usual, brute reality of administrative writing – harsh, bald even, and rarely if ever moving. Yet in the same section there follow numerous additional poems expanding on this theme. ‘A Prayer for Death Admin,’ for instance, enumerates in list fashion all the numbing points of engagement with officials and customer representatives, yet somehow loses impact in the wake of the earlier poem. Some judicious editing for length and cumulative effect might have helped, here – as Larkin noted in ‘Dockery and Son’, “Why did he think adding meant increase?/To me it was dilution.”

A later poem, “The Hymn of Him’, is a marvel of innovation and grace, practically reinventing the list-poem on a single page:

The lip of him, the map of him, the mop, the nap of him, the nip of him, the pep; the pip of him, the pup of him, the quip, the rap of him, the rep of him, the rip.It revels in personal, human diversity, not ducking anything less flattering (“the fop of him, the gap of him”) while celebrating a partner’s splendid variety, and mourning his loss, especially in a quiet but devastating conclusion:

The ship of him, the shop of him, the sh’up, the chap of him, the chip of him, the chop.The last suggestion – of a splintering, a potential coming apart of life, even of coherent memories – resonates through the whole collection. But the poet returns over and again to new versions of the list (‘All the Never You Can Carry,’ ‘Relationship as Covered Reservoir,’ and perhaps most pointedly ‘Your Brain’) giving the reader a sense of retreading ground (albeit inventively) and perhaps diminishing returns.

To return to the idea of a slim volume versus a thicker one, it is easy to object that exploring, memorialising and celebrating a whole life – even one cut short – requires as much time and space as it requires, regardless of the demands this may place on a reader. There is some justice to this argument. Yet, perversely, the practice of assembling a collection has its own implacable logic. What might work in, say, a published journal or longer non-fiction work – accumulation of detail, the gradual building of a comprehensive portrait – can work against the impact of a poetry collection.

As the first line of ‘Hand Puppets’ suggests, “Whenever I stop and think of you at your youest”, we best perceive the terrible processes of a death, its multitudinous adjustments, through well-chosen highlights, lowlights, rather than a piling-up of the same. Stephenson further notes (with a degree of ambivalence) in the title poem that the collection of moments sometimes brings its own pressures, and perhaps distortions. Overall, Stephenson stops short of the latter possibility and his lines resonate with a sense of what might have been: