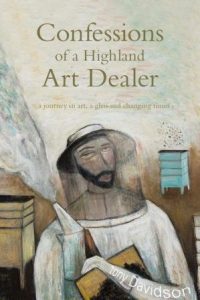

CONFESSIONS OF A HIGHLAND ART DEALER: Kate Ashton reviews a memoir full of hope and persistence by Tony Davidson

Confessions of a Highland Art Dealer

Tony Davidson

Woodwose Books

ISBN 9781739655716

£8.99

Confessions of a Highland Art Dealer

Tony Davidson

Woodwose Books

ISBN 9781739655716

£8.99

Tony Davidson is his own man: once nomad, now confirmed Highlander, the sometime penniless hippy is now a slightly more monied but no less free spirit, owner of a thriving art gallery in northern Scotland. His journey here, as narrated in this memoir, is extraordinary, unlikely, and inspiring. Davidson navigates neither by convention nor compromise.

Immune to the posing, preciousness, and petty vanities of the art establishment, he has spent the past quarter of a century pouring every ounce of his strength and energy into realising his gallery in a remote glen near Beauly (from the French beau lieu: beautiful place; Scottish Gaelic: A’ Mhanachainn). In the process he has met and cultivated an eclectic mix of artists and sponsors, now joined by a constant stream of art-lovers who come and return for the shows he curates with a discerning eye for the landscape and culture of his surroundings.

Among the regulars is the coterie of local gracious ladies who supplied pots of hot homemade soup for early exhibition openings, along with endless encouragement. Through the majestic, restored nave wander too tweed-clad hunters from local estates, and tourists surprised by the sudden dawning of a church just off the rural road. Occasionally, an oil magnate purrs up to the gallery via Aberdeen in a chauffeur-driven limousine. They arrive in walking boots or beaten-up old bangers, and when inadvertently Davidson’s left the door open, they’ve taken a leisurely look around and sometimes left a cheque. The cheques have grown exponentially meanwhile, in both size and frequency – but Davidson never forgets his seasonal ‘dog-food days’. Everyone in the arts has been hit hard since the 2008 banking crash and Davidson never saves for famine, but rides it out ‘on baked potatoes, dim bulbs and practical skills.’ Above all, on faith.

He is an enigmatic character, part intuitive savant, part savvy entrepreneur. There’s something knowing about him, but it’s as inaccessible as the spirit of Kilmorack. Driving to the church for the first time in March 1995 with its then owner, ‘Black Allan in a small maroon van tilted to one side, and me in an old, almost-ready-to-ditch Ford Sierra,’ he has no idea why or how Black Allan owns the place and doesn’t ask. ‘It’s just what Black Allan does. He collects neglected and wonderful things, a magpie of the mysterious.’ This is his secret treasure.

‘Note,’ observes Black Allan in his soft Inverness accent, ‘original lime hurling. Ornate hand-forged door furnishings, authentic but worn leaded paint and footworn Caithness flagstone’…he ‘makes a show of finding the key’, to uninterrupted architectural commentary. When the door opens Davidson indeed notes everything: old fenestration, glass thin enough to allow light to pour in over angled window shelves. Leaping herringbone roof and faded pink washed walls; narrow-planked flooring. Built in 1835 to be the biggest building in the community, the church exterior is classic Georgian, inside mock Gothic.

The old waterfall nearby, explains Black Allan, is now dammed and the healing spring forgotten, but Davidson can already feel the untamed energy of the place. Above them crows wheel, cawing a warning that human beings are not welcome here; the building itself ‘lies half asleep, one eye open like a dolphin.’ An assortment of ancient furniture and Black Allan’s ‘magician’s cabinet’, a six-sided structure of cobweb-thin silk with ornate finial, ‘too old to touch’ clutter the interior. ‘I may,’ announces Black Allan quietly, ‘should a suitable purchaser be found, be in a position of allowing this fine building to change ownership. I can see that you like beautiful things.’

The twenty-seven-year-old he has in prospect is an impecunious sibling soul: ‘Rules for Black Allan are a plaything. At least ten different pseudonyms help him avoid various authorities.’ Beyond the church lie the western hills, the glen crowded with old trees, wide-flowing river, and the yellowing Scottish dusk. ‘Maybe we could come to some mutually agreeable solution?’ hints Allan. Davidson’s laconic ‘Aye’ will be followed by a parade of worthiness tests as the vendor reels him in and out of ‘the game of a man between surfaces.’

By the end of the summer of 1995 the new custodian of Kilmorack church has passed muster and assimilated much wisdom, like the Latin names for diseases of old buildings: ‘Serpular lacrymans, dry rot, sounded almost romantic, like part of a requiem’; lime mortar, he has learnt, is holy; cement evil. There follow months of manual labour. Davidson dislodges himself from the drinking dens of Inverness and begins living wherever there’s a room near the church. Helped by an old DIY book, he weatherproofs and provides the building with running water, flushing toilet, and electricity. Eventually he gives up commuting and moves into the church’s upstairs gallery. Surviving mainly on oatcakes, he brews coffee on a camping stove, works barefoot, sunbathes when the sun shines and bathes in the river.

Meanwhile, all comers are offered due Highland hospitality. Sometimes this includes a glimpse of stray socks adorning the upper level. One Sunday midday after a wedding party the night before Tony hears the church doors open and, convinced it’s about 7a.m., leaves a bridesmaid slumbering on his upstairs futon to serve his visitors coffee dressed only in a towel.

Long before the Planning Department at Highland Council has got around to perusing his ‘reuse’ building application for the gallery, he begins firing off invitations to local artists to show their work at Kimorack. He has two rules, number one being to start at the top and work down: ‘Bottom feeders do not become sharks.’ One of his first artists, Allan MacDonald is a traditional churchgoing Highlander: ‘I’ll let you show my paintings, but maybe not on a Sunday. You’ll not be here long. I’ll give you six months before you give up and that’ll be a shame.’ He paints part-time, he says, and for the rest delivers ‘undrinkable’ locally made wine… ‘Hopefully, one day…’ He would drop by occasionally while Tony oscillated between preparations for his Grand Opening and opening letters from the Highland Council.

June 1996 finds Davidson glorying in his mythical domain, just as one thousand and four hundred years earlier St Columba and his followers travelled down nearby Loch Ness, euphoric enough amidst the glorious landscape to see a monster. He was still waiting for the Highland Council to bless his church repurposing from religion to commerce. He knew there was some local opposition. At last, the refusal letter arrived. All his efforts wasted, plus £270 lost application fee.

He didn’t blame the planners, just bureaucracy, rules, cogs in wheels. Reminded of a long-ago fancy-dress party held by a town planner in his converted school somewhere south of here, Davidson recalled how at midnight the host had ripped off his long black vicar’s frock to reveal suspenders and a kinky top. It had been a great party… and he was a town planner! Tony finds his number and phones. The response is unequivocal: they can’t refuse, ridiculous. It’s got to be the best possible use for a church. Tony could sue Highland Council for this! He must sue! ‘At the very least, appeal.’ The appeal is promptly filed, and Highland Council overruled by the Secretary of State in Edinburgh. The long wait for approval resumes, but meanwhile more artists ask to show at Kilmorack. Now he had ten.

June 20th, 1997, the Grand Opening of the Kilmorack Gallery. As confounded by public enthusiasm as by the momentous occasion and demands for an opening address, the antique-kilt-clad Davidson knew what was expected of him and complied with typical frugality: ‘I am not used to giving speeches, so I’ll keep it short. Thank you for coming. I wish I could thank more people, but it’s been a bit of a lot of work really and I did most of it myself. Thank you for coming. Shit, that is a bit short, and I must thank others too.’ Noting the expectant faces of ‘Inverness’s most economically viable’ and devoid as ever of sycophancy, he added, ‘A big thank you to the artists for letting me show their work. It wouldn’t be possible without them. You, me, and the artists. That’s it. It’s a bit short isn’t it but that’s always good.’

An immaculate grey suit among the recirculating crowd ignites in the gallery owner only the tiniest flicker of self-doubt, soon doused: ‘Maybe he could have done with a longer speech or a special mention, like they do in London.’ But Davidson is now definitively launched on his own path, nimble and versatile enough both to take on the digital revolution and fully appreciate its weaknesses, he carefully preserves the Highland ethos while installing internet,  designing a website and adjusting his business model accordingly. It works. The Kilmorack Gallery goes from strength to strength: savvy, quirky and sophisticated as a Lamborghini – an apt enough analogy for an art gallery whose progenitor gives a loving mention in his narrative to every car bought, sold, or disintegrating along the way.

designing a website and adjusting his business model accordingly. It works. The Kilmorack Gallery goes from strength to strength: savvy, quirky and sophisticated as a Lamborghini – an apt enough analogy for an art gallery whose progenitor gives a loving mention in his narrative to every car bought, sold, or disintegrating along the way.

Oct 17 2023

CONFESSIONS OF A HIGHLAND ART DEALER

CONFESSIONS OF A HIGHLAND ART DEALER: Kate Ashton reviews a memoir full of hope and persistence by Tony Davidson

Tony Davidson is his own man: once nomad, now confirmed Highlander, the sometime penniless hippy is now a slightly more monied but no less free spirit, owner of a thriving art gallery in northern Scotland. His journey here, as narrated in this memoir, is extraordinary, unlikely, and inspiring. Davidson navigates neither by convention nor compromise.

Immune to the posing, preciousness, and petty vanities of the art establishment, he has spent the past quarter of a century pouring every ounce of his strength and energy into realising his gallery in a remote glen near Beauly (from the French beau lieu: beautiful place; Scottish Gaelic: A’ Mhanachainn). In the process he has met and cultivated an eclectic mix of artists and sponsors, now joined by a constant stream of art-lovers who come and return for the shows he curates with a discerning eye for the landscape and culture of his surroundings.

Among the regulars is the coterie of local gracious ladies who supplied pots of hot homemade soup for early exhibition openings, along with endless encouragement. Through the majestic, restored nave wander too tweed-clad hunters from local estates, and tourists surprised by the sudden dawning of a church just off the rural road. Occasionally, an oil magnate purrs up to the gallery via Aberdeen in a chauffeur-driven limousine. They arrive in walking boots or beaten-up old bangers, and when inadvertently Davidson’s left the door open, they’ve taken a leisurely look around and sometimes left a cheque. The cheques have grown exponentially meanwhile, in both size and frequency – but Davidson never forgets his seasonal ‘dog-food days’. Everyone in the arts has been hit hard since the 2008 banking crash and Davidson never saves for famine, but rides it out ‘on baked potatoes, dim bulbs and practical skills.’ Above all, on faith.

He is an enigmatic character, part intuitive savant, part savvy entrepreneur. There’s something knowing about him, but it’s as inaccessible as the spirit of Kilmorack. Driving to the church for the first time in March 1995 with its then owner, ‘Black Allan in a small maroon van tilted to one side, and me in an old, almost-ready-to-ditch Ford Sierra,’ he has no idea why or how Black Allan owns the place and doesn’t ask. ‘It’s just what Black Allan does. He collects neglected and wonderful things, a magpie of the mysterious.’ This is his secret treasure.

‘Note,’ observes Black Allan in his soft Inverness accent, ‘original lime hurling. Ornate hand-forged door furnishings, authentic but worn leaded paint and footworn Caithness flagstone’…he ‘makes a show of finding the key’, to uninterrupted architectural commentary. When the door opens Davidson indeed notes everything: old fenestration, glass thin enough to allow light to pour in over angled window shelves. Leaping herringbone roof and faded pink washed walls; narrow-planked flooring. Built in 1835 to be the biggest building in the community, the church exterior is classic Georgian, inside mock Gothic.

The old waterfall nearby, explains Black Allan, is now dammed and the healing spring forgotten, but Davidson can already feel the untamed energy of the place. Above them crows wheel, cawing a warning that human beings are not welcome here; the building itself ‘lies half asleep, one eye open like a dolphin.’ An assortment of ancient furniture and Black Allan’s ‘magician’s cabinet’, a six-sided structure of cobweb-thin silk with ornate finial, ‘too old to touch’ clutter the interior. ‘I may,’ announces Black Allan quietly, ‘should a suitable purchaser be found, be in a position of allowing this fine building to change ownership. I can see that you like beautiful things.’

The twenty-seven-year-old he has in prospect is an impecunious sibling soul: ‘Rules for Black Allan are a plaything. At least ten different pseudonyms help him avoid various authorities.’ Beyond the church lie the western hills, the glen crowded with old trees, wide-flowing river, and the yellowing Scottish dusk. ‘Maybe we could come to some mutually agreeable solution?’ hints Allan. Davidson’s laconic ‘Aye’ will be followed by a parade of worthiness tests as the vendor reels him in and out of ‘the game of a man between surfaces.’

By the end of the summer of 1995 the new custodian of Kilmorack church has passed muster and assimilated much wisdom, like the Latin names for diseases of old buildings: ‘Serpular lacrymans, dry rot, sounded almost romantic, like part of a requiem’; lime mortar, he has learnt, is holy; cement evil. There follow months of manual labour. Davidson dislodges himself from the drinking dens of Inverness and begins living wherever there’s a room near the church. Helped by an old DIY book, he weatherproofs and provides the building with running water, flushing toilet, and electricity. Eventually he gives up commuting and moves into the church’s upstairs gallery. Surviving mainly on oatcakes, he brews coffee on a camping stove, works barefoot, sunbathes when the sun shines and bathes in the river.

Meanwhile, all comers are offered due Highland hospitality. Sometimes this includes a glimpse of stray socks adorning the upper level. One Sunday midday after a wedding party the night before Tony hears the church doors open and, convinced it’s about 7a.m., leaves a bridesmaid slumbering on his upstairs futon to serve his visitors coffee dressed only in a towel.

Long before the Planning Department at Highland Council has got around to perusing his ‘reuse’ building application for the gallery, he begins firing off invitations to local artists to show their work at Kimorack. He has two rules, number one being to start at the top and work down: ‘Bottom feeders do not become sharks.’ One of his first artists, Allan MacDonald is a traditional churchgoing Highlander: ‘I’ll let you show my paintings, but maybe not on a Sunday. You’ll not be here long. I’ll give you six months before you give up and that’ll be a shame.’ He paints part-time, he says, and for the rest delivers ‘undrinkable’ locally made wine… ‘Hopefully, one day…’ He would drop by occasionally while Tony oscillated between preparations for his Grand Opening and opening letters from the Highland Council.

June 1996 finds Davidson glorying in his mythical domain, just as one thousand and four hundred years earlier St Columba and his followers travelled down nearby Loch Ness, euphoric enough amidst the glorious landscape to see a monster. He was still waiting for the Highland Council to bless his church repurposing from religion to commerce. He knew there was some local opposition. At last, the refusal letter arrived. All his efforts wasted, plus £270 lost application fee.

He didn’t blame the planners, just bureaucracy, rules, cogs in wheels. Reminded of a long-ago fancy-dress party held by a town planner in his converted school somewhere south of here, Davidson recalled how at midnight the host had ripped off his long black vicar’s frock to reveal suspenders and a kinky top. It had been a great party… and he was a town planner! Tony finds his number and phones. The response is unequivocal: they can’t refuse, ridiculous. It’s got to be the best possible use for a church. Tony could sue Highland Council for this! He must sue! ‘At the very least, appeal.’ The appeal is promptly filed, and Highland Council overruled by the Secretary of State in Edinburgh. The long wait for approval resumes, but meanwhile more artists ask to show at Kilmorack. Now he had ten.

June 20th, 1997, the Grand Opening of the Kilmorack Gallery. As confounded by public enthusiasm as by the momentous occasion and demands for an opening address, the antique-kilt-clad Davidson knew what was expected of him and complied with typical frugality: ‘I am not used to giving speeches, so I’ll keep it short. Thank you for coming. I wish I could thank more people, but it’s been a bit of a lot of work really and I did most of it myself. Thank you for coming. Shit, that is a bit short, and I must thank others too.’ Noting the expectant faces of ‘Inverness’s most economically viable’ and devoid as ever of sycophancy, he added, ‘A big thank you to the artists for letting me show their work. It wouldn’t be possible without them. You, me, and the artists. That’s it. It’s a bit short isn’t it but that’s always good.’

An immaculate grey suit among the recirculating crowd ignites in the gallery owner only the tiniest flicker of self-doubt, soon doused: ‘Maybe he could have done with a longer speech or a special mention, like they do in London.’ But Davidson is now definitively launched on his own path, nimble and versatile enough both to take on the digital revolution and fully appreciate its weaknesses, he carefully preserves the Highland ethos while installing internet, designing a website and adjusting his business model accordingly. It works. The Kilmorack Gallery goes from strength to strength: savvy, quirky and sophisticated as a Lamborghini – an apt enough analogy for an art gallery whose progenitor gives a loving mention in his narrative to every car bought, sold, or disintegrating along the way.

designing a website and adjusting his business model accordingly. It works. The Kilmorack Gallery goes from strength to strength: savvy, quirky and sophisticated as a Lamborghini – an apt enough analogy for an art gallery whose progenitor gives a loving mention in his narrative to every car bought, sold, or disintegrating along the way.