Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas.

Tate Britain, 28th Sept 2023 to 14th January 2024.

It is clear from this retrospective of Sarah Lucas’s thirty-five year career that an obsession with tits, toilets, cigarettes, shoes and chairs informs much of her work. Her relentless focus is on the human body with its range of appetites, cravings and needs. The title of the show is, after all, the street term for nitrous oxide, the intoxicating substance delivered in the little silver canisters which litter the urban environment. To be more specific, her work is mostly concerned with the female body and how it is perceived by men.

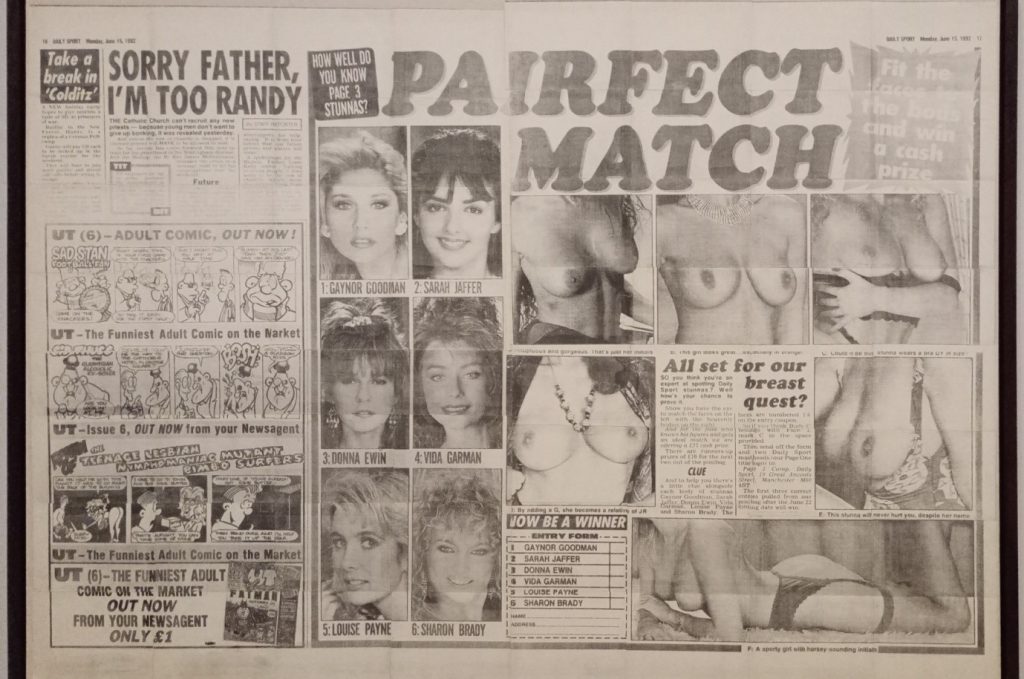

Coming to prominence in the early 1990’s, Lucas was clearly concerned with all things sexual. In the first room there are huge blow-ups (such as Pairfect Match, 1992) of the sort of titillating double-page spread so beloved of the sleazier tabloids of the time, and to ram the point home in the first corner is a mechanical arm’s reciprocating motion above a chair in a piece called Wanker (1999).

Pairfect Match, 1992. Phototransfer on paper laid on canvas. Courtesy of Sadie Coles HQ, London.

The use of everyday objects and materials (breeze blocks, tights, vegetables) is also a constant theme, the artist claiming that their readiness for quick use enhances the spontaneity of her work.

In 1997 Lucas made the first of her “Bunny” sculptures: female forms with multiple breasts and long and thin spread legs, all draped over a supporting chair. She has returned to the theme repeatedly. There are no faces or heads to support the idea of identification – it is the raw sexual being we are invited to consider. The early examples are predominantly of soft material – tights filled with stuffing; more recently she achieves a similar effect with concrete or bronze.

TITTIPUSSIDAD, 2018. Bronze, concrete, cast iron. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Lucas herself appears in a good many of the works. In the large second room three of the walls are covered by a series of massive black and white photographs of her eating a banana. Cheeky, huh? But by now one might be asking: “So what?” Yes, her work is playful, suggestive, and one could say, disturbing, but I would add the word ‘mildly’ before each of those. We are now so used to discussions of sex and sexuality, of the male gaze, of the position of women in society that the show, up to this point, does not seem to be saying anything of substantial additional importance.

Eating a Banana (1990) dominates the many Bunny sculptures in the second room.

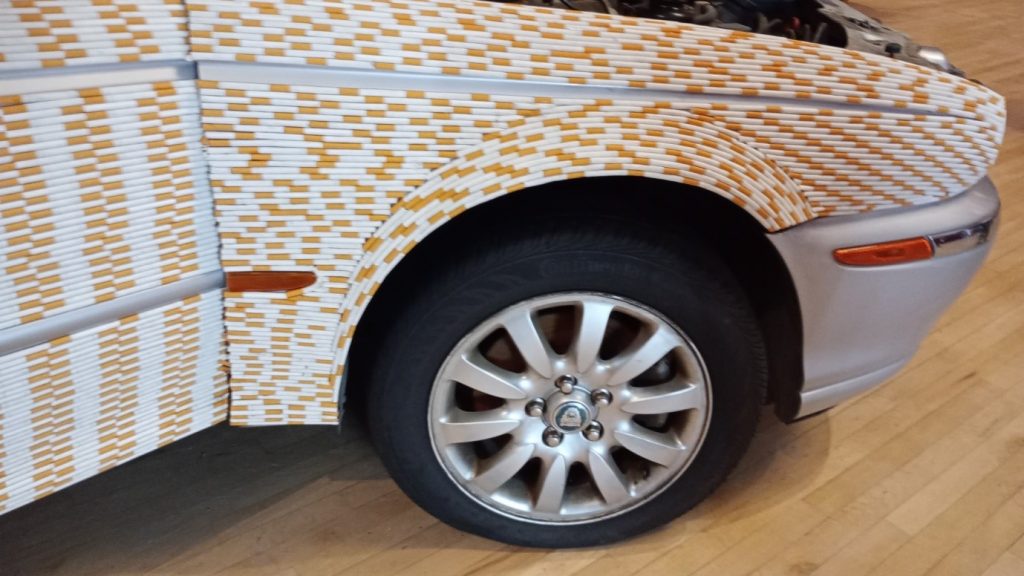

The third room presents work which is much more interesting. My favourite piece, This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven (2018) has the two halves of a wrecked car. In a macabre way it reminds one of Warhol’s pictures of car wrecks from the 1960’s. But here Lucas adds more meaning. The rear half of the car (a wealthy man’s car, let’s face it) is burned out – we can only imagine the horrible fate of its supposed occupants. But as we look closer at the bodywork of the front half and at the seats we realise they are completely covered with a pattern of real cigarettes, slyly suggesting, perhaps, that another flame-borne fatality awaits the unwary. And again, looking down from the walls, are more massive portraits of Lucas, in colour now and wreathed by her own cigarette smoke.

Detail: This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven, 2018. Car, cigarettes, glue. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The move into harder materials is well represented in this third room. A large white bread Sandwich (2004 to 2020) made from Jesmonite and polystyrene looks particularly unappetising, whereas I was won over completely by the chair and footstool, Eames Chair (2015) rendered in bronze and concrete. It is actually the pieces with no human form which come across as the strongest: I particularly liked the sofa bed and the chair, each pierced by threatening neon tubes (Fuck Destiny, 2000 and Exacto, 2018).

Exacto, 2018. Chair, fluorescent lights. Courtesy the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York.

In summary, Sarah Lucas’s work encourages a close questioning of many of our domestic British attitudes but, to my mind, in a pleasing but not particularly pressing way. Of her contemporaries Damien Hirst’s examinations of mortality are more profound; Rachel Whiteread’s work in concrete more serious.

In the garden space at the front of the Tate are two huge marrows, named Florian and Kevin, rendered in concrete. But vegetables as a metaphor for male genitalia? A bit passé, don’t you think?

© Graham Buchan, 2023.

Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas.

Tate Britain, 28th Sept 2023 to 14th January 2024.

It is clear from this retrospective of Sarah Lucas’s thirty-five year career that an obsession with tits, toilets, cigarettes, shoes and chairs informs much of her work. Her relentless focus is on the human body with its range of appetites, cravings and needs. The title of the show is, after all, the street term for nitrous oxide, the intoxicating substance delivered in the little silver canisters which litter the urban environment. To be more specific, her work is mostly concerned with the female body and how it is perceived by men.

Coming to prominence in the early 1990’s, Lucas was clearly concerned with all things sexual. In the first room there are huge blow-ups (such as Pairfect Match, 1992) of the sort of titillating double-page spread so beloved of the sleazier tabloids of the time, and to ram the point home in the first corner is a mechanical arm’s reciprocating motion above a chair in a piece called Wanker (1999).

Pairfect Match, 1992. Phototransfer on paper laid on canvas. Courtesy of Sadie Coles HQ, London.

The use of everyday objects and materials (breeze blocks, tights, vegetables) is also a constant theme, the artist claiming that their readiness for quick use enhances the spontaneity of her work.

In 1997 Lucas made the first of her “Bunny” sculptures: female forms with multiple breasts and long and thin spread legs, all draped over a supporting chair. She has returned to the theme repeatedly. There are no faces or heads to support the idea of identification – it is the raw sexual being we are invited to consider. The early examples are predominantly of soft material – tights filled with stuffing; more recently she achieves a similar effect with concrete or bronze.

TITTIPUSSIDAD, 2018. Bronze, concrete, cast iron. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Lucas herself appears in a good many of the works. In the large second room three of the walls are covered by a series of massive black and white photographs of her eating a banana. Cheeky, huh? But by now one might be asking: “So what?” Yes, her work is playful, suggestive, and one could say, disturbing, but I would add the word ‘mildly’ before each of those. We are now so used to discussions of sex and sexuality, of the male gaze, of the position of women in society that the show, up to this point, does not seem to be saying anything of substantial additional importance.

Eating a Banana (1990) dominates the many Bunny sculptures in the second room.

The third room presents work which is much more interesting. My favourite piece, This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven (2018) has the two halves of a wrecked car. In a macabre way it reminds one of Warhol’s pictures of car wrecks from the 1960’s. But here Lucas adds more meaning. The rear half of the car (a wealthy man’s car, let’s face it) is burned out – we can only imagine the horrible fate of its supposed occupants. But as we look closer at the bodywork of the front half and at the seats we realise they are completely covered with a pattern of real cigarettes, slyly suggesting, perhaps, that another flame-borne fatality awaits the unwary. And again, looking down from the walls, are more massive portraits of Lucas, in colour now and wreathed by her own cigarette smoke.

Detail: This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven, 2018. Car, cigarettes, glue. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The move into harder materials is well represented in this third room. A large white bread Sandwich (2004 to 2020) made from Jesmonite and polystyrene looks particularly unappetising, whereas I was won over completely by the chair and footstool, Eames Chair (2015) rendered in bronze and concrete. It is actually the pieces with no human form which come across as the strongest: I particularly liked the sofa bed and the chair, each pierced by threatening neon tubes (Fuck Destiny, 2000 and Exacto, 2018).

Exacto, 2018. Chair, fluorescent lights. Courtesy the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York.

In summary, Sarah Lucas’s work encourages a close questioning of many of our domestic British attitudes but, to my mind, in a pleasing but not particularly pressing way. Of her contemporaries Damien Hirst’s examinations of mortality are more profound; Rachel Whiteread’s work in concrete more serious.

In the garden space at the front of the Tate are two huge marrows, named Florian and Kevin, rendered in concrete. But vegetables as a metaphor for male genitalia? A bit passé, don’t you think?

© Graham Buchan, 2023.

By Graham Buchan • art, exhibitions, year 2023 • Tags: art, exhibitions, Graham Buchan