We Want To Be Sung To While We Drown

Poetry review – NEPTUNE’S PROJECTS: Guy Russell surveys an ambitious collection by Rishi Dastidar which is in effect an elegy for our world

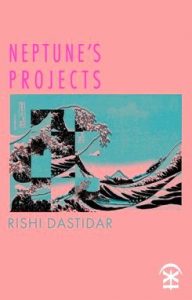

Neptune’s Projects

(a/k/a Now That’s What I Call Hyperobject Ballads)

Rishi Dastidar

Nine Arches

ISBN: 978-1-913437-68-8

£10.99

Neptune’s Projects

(a/k/a Now That’s What I Call Hyperobject Ballads)

Rishi Dastidar

Nine Arches

ISBN: 978-1-913437-68-8

£10.99

Environmental disaster has been called a ‘hyperobject’: something whose magnitude and pervasiveness we struggle to comprehend. Hence the blindfolding, the denials, the excuses. But perhaps it offers a role for poetry in the end-times, distilling such an immensity in a way that helps us grasp what’s happening, at least emotionally?

This collection has a go, anyway, starting from the ready assumption that the near future is going to be really bad or possibly apocalyptic. Neptune, who voices a number of these poems, has a sometimes chirpy, sometimes chippy tone which can also flip from magisterial (‘the rage and torment and vengeance I could summon with just a beat of my heart’) to avuncular (‘forever is a long time, boy, let me tell you’), to campish style-guru (‘Try the gin with ginger and peppercorn tonic – it’s divine’). The god, or some similar quasi-omniscient voice, tells (or reminds) us how we’re ‘failing’: ‘contemplating changing, but / then believing that the end cannot be near’, and so glazed that we’ll regard Armageddon as a spectacle and ‘eat popcorn’ at it. We’re asked, ‘Would you get it more if I tattooed a Plimsol [sic] Line on your foreheads?’ and ‘What will you do in the Novacene?’ Voices from the future retro-predict that we ‘couldn’t adjust in time’, and tell us: ‘get over yourselves’. ‘Sapiens! I remember them! […] Never seen a death wish like it.’ The anger, sarcasm and despairing laughter are very contemporary.

Nearly halfway in, the focus narrows, in a series of poems labelled “Pretanic, Edition 2” (following on from “Edition 1” in Dastidar’s first collection). Here we’re told (or reminded) that Britain is in hock to its (our) imperial past, WW2 nostalgia, and outmoded exceptionalism, with rather stock imagery of Brexit cliff-edges, and lorry-park Kent. It’s followed by a section called “Crisis or War Comes”, whose unpunctuated and sinister poems sound like fragments from a civil defence document, complete with simplified vocabulary and concerned, authoritarian tone:

in just a short time

your life can become

problematic

[…]

think about how you will

be able to cope with

society’s not working

Both these sections fit the overall disaster motif, although less directly the oceanic one that furnishes the title. Among the sea-themed poems, there’s no lack of shipwreck, drowning, icebergs, plastic gyres, collapsing ice shelves and sea-level rise. Neptune admits that his former ability to give ‘comfort, consolation, absolution, joy’ is diminishing, but the book has its moments of respite. Other aspects of the ocean aren’t forgotten: how little of it is still known (about 5%, with no Google Earth equivalent), its opportunities for escape (say, from lockdown); and its sheer delight (‘the waves speak happiness’). There’s the sea as scenic backdrop to a posh restaurant, as a supercomputer

Aren’t amoeba and plankton actually biological transistors, waiting to be

switched on by your longing […]?

or sentient like in Solaris. And Neptune imagines what it’s like for someone to dive into him:

[…] that moment when fear and exhilaration and gravity collide in me;

what the rush of me feels like on his skin, how the flakes of seaweed that

are older than both of us try to stick to him but can’t […]

There are poems on watery-themed paintings, and a birthday poem to a friend who’s made a film about a mermaid and ocean plastic. This book has fewer love poems than long-standing Dastidar fans might have hoped for, and there’s nothing as fabulous as ‘A leopard parses his concern’; here love, thematically enough, is often like drowning: ‘inhale the sea’, say lovers; ‘take me into your depths’.

We aren’t finally offered any hope, unless banalities like ‘the end is actually the best beginning’ are to be read straight-faced (unlikely), and the injunction to ‘be the sea lion of your life | | applaud your delight at being’ is perhaps the nearest attempt at consolation. The book signs off with: ‘All I’ve ever wanted to do is live by the sea./ Ironic isn’t it?’ by which point the many meanings of ‘live by the sea’ have become sufficiently unmissable that the ‘ironic’ must be… ironic? The book’s got some lovely and arresting moments, and if its ambition outdoes its execution, well, its ambition is set very high. What really would an elegy for the world sound like?

Guy Russell reviews poetry regularly for Tears in the Fence and its blog, and in the past he’s also written for Thumbscrew, Stride, Poetry Quarterly Review and New Statesman. He has a pamphlet, Like Basically (Dreich Press), and has won the Leicester Poetry Competition and the Cannon ‘Sonnet or Not’ Competition.

Sep 23 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Rishi Dastidar

We Want To Be Sung To While We Drown

Poetry review – NEPTUNE’S PROJECTS: Guy Russell surveys an ambitious collection by Rishi Dastidar which is in effect an elegy for our world

Environmental disaster has been called a ‘hyperobject’: something whose magnitude and pervasiveness we struggle to comprehend. Hence the blindfolding, the denials, the excuses. But perhaps it offers a role for poetry in the end-times, distilling such an immensity in a way that helps us grasp what’s happening, at least emotionally?

This collection has a go, anyway, starting from the ready assumption that the near future is going to be really bad or possibly apocalyptic. Neptune, who voices a number of these poems, has a sometimes chirpy, sometimes chippy tone which can also flip from magisterial (‘the rage and torment and vengeance I could summon with just a beat of my heart’) to avuncular (‘forever is a long time, boy, let me tell you’), to campish style-guru (‘Try the gin with ginger and peppercorn tonic – it’s divine’). The god, or some similar quasi-omniscient voice, tells (or reminds) us how we’re ‘failing’: ‘contemplating changing, but / then believing that the end cannot be near’, and so glazed that we’ll regard Armageddon as a spectacle and ‘eat popcorn’ at it. We’re asked, ‘Would you get it more if I tattooed a Plimsol [sic] Line on your foreheads?’ and ‘What will you do in the Novacene?’ Voices from the future retro-predict that we ‘couldn’t adjust in time’, and tell us: ‘get over yourselves’. ‘Sapiens! I remember them! […] Never seen a death wish like it.’ The anger, sarcasm and despairing laughter are very contemporary.

Nearly halfway in, the focus narrows, in a series of poems labelled “Pretanic, Edition 2” (following on from “Edition 1” in Dastidar’s first collection). Here we’re told (or reminded) that Britain is in hock to its (our) imperial past, WW2 nostalgia, and outmoded exceptionalism, with rather stock imagery of Brexit cliff-edges, and lorry-park Kent. It’s followed by a section called “Crisis or War Comes”, whose unpunctuated and sinister poems sound like fragments from a civil defence document, complete with simplified vocabulary and concerned, authoritarian tone:

Both these sections fit the overall disaster motif, although less directly the oceanic one that furnishes the title. Among the sea-themed poems, there’s no lack of shipwreck, drowning, icebergs, plastic gyres, collapsing ice shelves and sea-level rise. Neptune admits that his former ability to give ‘comfort, consolation, absolution, joy’ is diminishing, but the book has its moments of respite. Other aspects of the ocean aren’t forgotten: how little of it is still known (about 5%, with no Google Earth equivalent), its opportunities for escape (say, from lockdown); and its sheer delight (‘the waves speak happiness’). There’s the sea as scenic backdrop to a posh restaurant, as a supercomputer

or sentient like in Solaris. And Neptune imagines what it’s like for someone to dive into him:

There are poems on watery-themed paintings, and a birthday poem to a friend who’s made a film about a mermaid and ocean plastic. This book has fewer love poems than long-standing Dastidar fans might have hoped for, and there’s nothing as fabulous as ‘A leopard parses his concern’; here love, thematically enough, is often like drowning: ‘inhale the sea’, say lovers; ‘take me into your depths’.

We aren’t finally offered any hope, unless banalities like ‘the end is actually the best beginning’ are to be read straight-faced (unlikely), and the injunction to ‘be the sea lion of your life | | applaud your delight at being’ is perhaps the nearest attempt at consolation. The book signs off with: ‘All I’ve ever wanted to do is live by the sea./ Ironic isn’t it?’ by which point the many meanings of ‘live by the sea’ have become sufficiently unmissable that the ‘ironic’ must be… ironic? The book’s got some lovely and arresting moments, and if its ambition outdoes its execution, well, its ambition is set very high. What really would an elegy for the world sound like?

Guy Russell reviews poetry regularly for Tears in the Fence and its blog, and in the past he’s also written for Thumbscrew, Stride, Poetry Quarterly Review and New Statesman. He has a pamphlet, Like Basically (Dreich Press), and has won the Leicester Poetry Competition and the Cannon ‘Sonnet or Not’ Competition.