Poetry review – AD HOC: Charles Rammelkamp reviews a highly original debut collection by Hayden Bergman

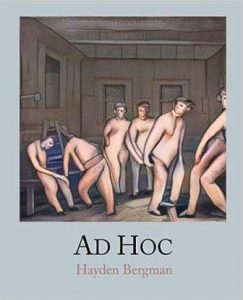

Ad Hoc

Hayden Bergman

BlazeVOX [books], 2023

ISBN: 978-1609644390

80 pages $18.00

Ad Hoc

Hayden Bergman

BlazeVOX [books], 2023

ISBN: 978-1609644390

80 pages $18.00

Life is bad and confusing, except for when it’s good.

The opening line from Hayden Bergman’s poem, “If No Other in the World Be Aware (or Each), I Sit Content” crystallizes the overall point of view and poetic approach of the melancholy but oddly reverent poems about rural life in America in his remarkable debut collection. Bergman’s poems sprawl across the page, with titles to match: “Due to the Price Increase on Emotion Do Not Expect a Revelation,” “Let the Children Speak on Memory Alone, as Birds are Born to Fly,” and “The Subject Separated Itself, Leaving Us Free to Choose Whether We Would Form a Part of It” are examples. The complex titles, moreover, reflect the complicated and ambivalent point-of-view expressed throughout.

The title of the collection comes from the three-part poem. “Ad Hoc (I),” “Ad Hoc (II),”and “Ad Hoc (III),” though they can be seen as one poem, are distinct on their own pages in the book, with recurring references to work (“work that wasn’t holy, though the stubble ground / was gold”) and to the lure of the “down-street girls.” As in so many of the poems, the characters in “Ad Hoc” are pubescent teens and the poems reflect their desires and perspectives.

“Obiter Dictum,” for instance (“that which is said in passing”), takes place at a teenage beauty pageant (“which of these fine young ladies will be deemed / the winter’s beauty queen”). Bergman shows us the society women who are the judges (“women known / for their mashup activities of historic preservation, / young female development…”) but juxtaposes them with the salacious whispering of the teenaged boys, ripped apart by adolescent hormones, “rumors that they’ve heard about each girl

how this one fucks like a mechanical bull or that one sucks like an Oreck, no,

a Hoover,

though the girls have never done this, and the boys

don’t know a goddamn thing

Other poems likewise come in parts that appear on separate pages across the collection – “rurality” parts I, II and III, “Dishonours of the Flesh” parts I and II, and “Sight,” parts I, II and III. “Dishonours of the Flesh” deals with sex education and the poems are horrifying for the indoctrination and sheer terror inflicted on the youngsters, reflecting small-town attitudes toward sex as a moral issue. “The woman horrifies the kids with a genital warts slideshow,” “Dishonours of the Flesh (II)” begins, and after more dire warning, the poem ends on the forlorn question, presumably asked by a thoroughly cowed teenaged girl, “How do I know if I’m pregnant?”

Berman’s poems about smalltown rural Texas bring to mind Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, the voices and portraits of various citizens. There’s “Mr. Meyers, the whole town’s undertaker,” in “He Considered Himself a Moral Man, Responsible to Higher Authorities – Kimiko Hahn,” whom everyone in town says is always working: “when he sees you at the ballgame / or in line at the supermarket butcher counter, he’s sizing up your shoulders…,” already measuring you for a coffin. “Above the Clack of Dominoes, Miss Roma,” painting her nails, reflects about her husband. “I loved him, as required.” We also overhear Miss Brenda, “above the Greyhound’s groan,” reflecting on her own power. “Above the Wheezing Window Unit, Miss Betty” tweezing her eyebrows at the vanity, also reflects on her life in the quiet of the morning before husband and children demand her attention.

In “All the Men Had Jobs, and the Women, Yes, Had Automatic Chores” the young narrator eavesdrops on the women in the kitchen at a New Year’s party, while their men are all watching football on TV. They are talking about the grossness of the jewelry store bathroom, about the bra not fitting right at work and having to talk with the boss,

but I can feel, already, my patchy-bearded presence bending conversation

toward the tamer topics,

toward the Biddix family, and how their daughter

moved to Houston, came down with a sickness in her eye,

and how the doctor didn’t know,

and so, prescribed a medicine that costs too much…

The adjunct preacher is a recurring character. He appears in “Sunday Best,” the very first poem, and later in “They Were Not Disturbed by the Wails and Sounds of Things,” where, in Casa K, the best restaurant in town,

everyone

who’s anybody goes

to poke fun at the adjunct preacher’s fussy hair,

and how he does his voice like up and down,

his warbling proof he doesn’t have that much to say.

“Bull” similarly takes place in the barbershop of Raymond, “the only haircut man in town.” “Raymond flourishes the capes, soaps each neck for the glint of a razor’s edge.” More gossip and small-talk occur.

Bergman takes us where men “in camo and square boots pace through the aisles of the gun show,” in “There Is Much Confusion Between Land and Country.” Bergman contrasts these “hunters” with veterans on Veterans Day, the ones who “show up to mourn, / to practice a respect.” On Veterans Day, the hunters “feel as though they’re sharing in the dignity, / having never had to see a person’s face change / in the dirt.”

In his “Notes,” Bergman tells the reader that he draws on his experiences in the town of Winters, Texas, for the characters and locations of the poems in the collection. Winters is a town of roughly two and a half thousand residents in west central Texas. Without actually naming the town, in “What You Can Do” Bergman affectionately refers to “our flyway town,’ in a poem about the Dewey family farm, where the narrator worked “three bucks under minimum wage earned for tasks like tying odd branches / to each other,” so that “the monarchs had reserve to rest / their royal caravan when they came through,” a metaphor of families breaking up and moving on. The Deweys’ marriage ends.

The collection ends on the third “Sight” poem, another sequence about working at a manual labor job, this time in a silo, and the dust and silt cake the narrator’s eyes so that one morning he cannot see, and he panics shouts for his mother, who sees the problem, washes his face. The poem – and book – ends:

Filth washed away, I raised my face up to the mirror

and received sight forthwith.

Indeed, Ad Hoc is all about seeing. Hayden Bergman is a terrific noticer – the bad and confusing and the good, both.

Sep 10 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Hayden Bergman

Poetry review – AD HOC: Charles Rammelkamp reviews a highly original debut collection by Hayden Bergman

The opening line from Hayden Bergman’s poem, “If No Other in the World Be Aware (or Each), I Sit Content” crystallizes the overall point of view and poetic approach of the melancholy but oddly reverent poems about rural life in America in his remarkable debut collection. Bergman’s poems sprawl across the page, with titles to match: “Due to the Price Increase on Emotion Do Not Expect a Revelation,” “Let the Children Speak on Memory Alone, as Birds are Born to Fly,” and “The Subject Separated Itself, Leaving Us Free to Choose Whether We Would Form a Part of It” are examples. The complex titles, moreover, reflect the complicated and ambivalent point-of-view expressed throughout.

The title of the collection comes from the three-part poem. “Ad Hoc (I),” “Ad Hoc (II),”and “Ad Hoc (III),” though they can be seen as one poem, are distinct on their own pages in the book, with recurring references to work (“work that wasn’t holy, though the stubble ground / was gold”) and to the lure of the “down-street girls.” As in so many of the poems, the characters in “Ad Hoc” are pubescent teens and the poems reflect their desires and perspectives.

“Obiter Dictum,” for instance (“that which is said in passing”), takes place at a teenage beauty pageant (“which of these fine young ladies will be deemed / the winter’s beauty queen”). Bergman shows us the society women who are the judges (“women known / for their mashup activities of historic preservation, / young female development…”) but juxtaposes them with the salacious whispering of the teenaged boys, ripped apart by adolescent hormones, “rumors that they’ve heard about each girl

Other poems likewise come in parts that appear on separate pages across the collection – “rurality” parts I, II and III, “Dishonours of the Flesh” parts I and II, and “Sight,” parts I, II and III. “Dishonours of the Flesh” deals with sex education and the poems are horrifying for the indoctrination and sheer terror inflicted on the youngsters, reflecting small-town attitudes toward sex as a moral issue. “The woman horrifies the kids with a genital warts slideshow,” “Dishonours of the Flesh (II)” begins, and after more dire warning, the poem ends on the forlorn question, presumably asked by a thoroughly cowed teenaged girl, “How do I know if I’m pregnant?”

Berman’s poems about smalltown rural Texas bring to mind Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology, the voices and portraits of various citizens. There’s “Mr. Meyers, the whole town’s undertaker,” in “He Considered Himself a Moral Man, Responsible to Higher Authorities – Kimiko Hahn,” whom everyone in town says is always working: “when he sees you at the ballgame / or in line at the supermarket butcher counter, he’s sizing up your shoulders…,” already measuring you for a coffin. “Above the Clack of Dominoes, Miss Roma,” painting her nails, reflects about her husband. “I loved him, as required.” We also overhear Miss Brenda, “above the Greyhound’s groan,” reflecting on her own power. “Above the Wheezing Window Unit, Miss Betty” tweezing her eyebrows at the vanity, also reflects on her life in the quiet of the morning before husband and children demand her attention.

In “All the Men Had Jobs, and the Women, Yes, Had Automatic Chores” the young narrator eavesdrops on the women in the kitchen at a New Year’s party, while their men are all watching football on TV. They are talking about the grossness of the jewelry store bathroom, about the bra not fitting right at work and having to talk with the boss,

The adjunct preacher is a recurring character. He appears in “Sunday Best,” the very first poem, and later in “They Were Not Disturbed by the Wails and Sounds of Things,” where, in Casa K, the best restaurant in town,

“Bull” similarly takes place in the barbershop of Raymond, “the only haircut man in town.” “Raymond flourishes the capes, soaps each neck for the glint of a razor’s edge.” More gossip and small-talk occur.

Bergman takes us where men “in camo and square boots pace through the aisles of the gun show,” in “There Is Much Confusion Between Land and Country.” Bergman contrasts these “hunters” with veterans on Veterans Day, the ones who “show up to mourn, / to practice a respect.” On Veterans Day, the hunters “feel as though they’re sharing in the dignity, / having never had to see a person’s face change / in the dirt.”

In his “Notes,” Bergman tells the reader that he draws on his experiences in the town of Winters, Texas, for the characters and locations of the poems in the collection. Winters is a town of roughly two and a half thousand residents in west central Texas. Without actually naming the town, in “What You Can Do” Bergman affectionately refers to “our flyway town,’ in a poem about the Dewey family farm, where the narrator worked “three bucks under minimum wage earned for tasks like tying odd branches / to each other,” so that “the monarchs had reserve to rest / their royal caravan when they came through,” a metaphor of families breaking up and moving on. The Deweys’ marriage ends.

The collection ends on the third “Sight” poem, another sequence about working at a manual labor job, this time in a silo, and the dust and silt cake the narrator’s eyes so that one morning he cannot see, and he panics shouts for his mother, who sees the problem, washes his face. The poem – and book – ends:

Indeed, Ad Hoc is all about seeing. Hayden Bergman is a terrific noticer – the bad and confusing and the good, both.