HOLDING A POSE: John Lucas comments on an intriguing essay by Anthony Rudolf on the role of the artist’s model

Anthony Rudolf,

Models in Degas, Manet and the Pre-Raphaelites

fortnightlyreview.co.uk

Anthony Rudolf,

Models in Degas, Manet and the Pre-Raphaelites

fortnightlyreview.co.uk

Now here’s an unlooked for treasure. Most of us in the literary world know of Anthony Rudolf as a fine poet who is also the publisher of Menard Books as well as a critic and biographer – in particular of a major work on Isaac Rosenberg. And some are aware that for many years he was the partner of the great artist, Paula Rego, for whom he often modelled. Now comes his account, not merely of their relationship as artist and sitter, but of the relationships between other artists and their models. The result is one of the most absorbing, suggestive and intellectually stimulating meditations I have read of what such relationships entail.

‘Relationship’ can in the case of many artists be pitching it too high. Speaking of artists’ models, Degas said that ‘most of them are just poor girls who have a demanding job and barely make enough to live on… I know them well, you know, the little rats, from the time when they used to come and pose for me.’ Little rats? Insulting, demeaning, though such a term may be, it was apparently the soubriquet attached to girls in the corps de ballet of Parisian Opera, though as Rudolf notes, the girls were not so much selling their bodies for sex as for copying. Other women, such as Manet’s model, Mery Laurent, shared their favours between the artist and Mallarmé beside being a source for Proust’s Odette. And Manet also made use of Berthe Morrisot for what Rudolf calls two of his finest paintings, ‘the portrait with flowers and “The Balcony.”’

‘Relationship’ can in the case of many artists be pitching it too high. Speaking of artists’ models, Degas said that ‘most of them are just poor girls who have a demanding job and barely make enough to live on… I know them well, you know, the little rats, from the time when they used to come and pose for me.’ Little rats? Insulting, demeaning, though such a term may be, it was apparently the soubriquet attached to girls in the corps de ballet of Parisian Opera, though as Rudolf notes, the girls were not so much selling their bodies for sex as for copying. Other women, such as Manet’s model, Mery Laurent, shared their favours between the artist and Mallarmé beside being a source for Proust’s Odette. And Manet also made use of Berthe Morrisot for what Rudolf calls two of his finest paintings, ‘the portrait with flowers and “The Balcony.”’

And then there is ‘Pauline.’ One of the most interesting of the several models about whom Rudolf writes, ‘Pauline’ frequently modelled for Degas, the ‘grumpy genius,’ as Rudolf calls that great artist. Part of her work was to humour Degas, to know when to change the subject of their talk, to console him ‘about his fading eyesight and troublesome bladder,’ and to advise him ‘not to wander around Paris alone.’ She sounds more of a matron than a mistress, and Degas’s relationship with her was certainly very different from the customary behaviour toward models of the predatory Puvis de Chavannes, although, Rudolf says, de Chavannes ‘seems to have been civilised with Susan Valadon, his close friend and nude model and lover, and mother of Maurice Utrillo (whose father may have been Puvis.)’ And if all this makes you feel a bit dizzy you can always murmur to yourself the words of the great Nancy Banks Smith when trying to recount the plot of an especially convoluted TV drama, ‘Oh, do keep up, Monica.’

But preferably you can consider the implications of Rudolf’s arresting remark that in thinking about the inter-subjectivity of painter and model, he finds himself reflecting on his position as Paula Rego’s model and how ‘I swivel my eyes and look at [her] out of curiosity and also with emotion: I and Thou, Thou and I, although I, her Thou am/is also an It… and one has no choice if Paula is to make the picture work.’ How strange, after all, to be both humanly engaged in the making of a painting and at the same time, reified by the artist/maker. Rudolf’s meditation puts me in mind of that moment in Our Mutual Friend when Bradley Headstone comes unexpectedly on the villainous Rogue Riderhood and thinks ‘Here is an instrument. Can I use it?’ Portraiture can’t but help being instrumental, a word the O.E.D. defines as ‘serving as an instrument or means to achieve a particular end or purpose.’ A model is often, perhaps usually, without agency. But not always. As Rudolf adds, ‘Posing for [Paula] is a pleasure and a privilege but there are moments when your mind wanders and your eye wanders and you wonder how long you can hold the pose without moving.’ The sentence fascinates me in the way it registers the model as a ‘you’, someone who is both the self and a not-self, who is an other, and there is also the intriguing ambiguity in that conscious punning (is it?) on wander/wonder. The mind is free to roam even as the body is held in place.

A different, but no less fascinating matter. Rudolf makes a persuasive case for one model being used in two very different paintings and of the peculiar effect this has on our reception of both. He is struck by the close resemblance between the face of General Miramon as depicted in Manet’s famous ‘Execution of Emperor Maximilian’ to that of the man in Henri Gervex’s ‘Rollo’ who stands, half-dressed, at the bedroom window of the room looking toward the bed where he and his lover have spent the night and where she now sprawls naked in satiated sleep. Not merely his face, with its distinctive moustache and beard, but his rumpled shirt, look very like that of the General’s. Rudolf tells us that the model for Miramon was Manet’s friend, the violinist, Damourette, which adds piquancy to the likelihood that the one man posed for both paintings. Delivering love to death wrapped in a rumpled sheet, you might say.

I have to admit that I am less interested in what Rudolf has to tell us about Rossetti and his models, Lizzie Siddal and Fanny Comforth, probably because the artist himself, however considerate he may have been to the various women in his life, seems to me less interesting, indeed on occasions (as in ‘Found’) verging on the incompetent. Look at the failure to control perspective in the drawing of the cart on which the netted ‘found’ lamb stands, how inexpert the use of colour – and anyway, how yukky the symbolism, how trite the moralising message of awakening conscience. It’s good to learn that Paula Rego’s favourite Pre-Raphaelite painter was Augustus Egg, who in many ways is hardly of the Brotherhood. Without having to give the thumbs-up to Rossetti, I can sympathise with Rudolf’s appreciative words about the Siddal and Comforth ‘Sisterhood.’

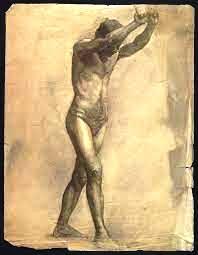

But far superior to either is Gwen John. If and when Rudolf develops his penetrative accounts of the models he writes about here, as he hints he will do, I hope he will have something to say about John, both as artist and model to Auguste Rodin, prepared to use her lithe body to adopt and maintain very demanding poses – ‘Je vain vous dormer des poses extraordinaire aussi Bien que les poses classiques, car je suis souple’ she wrote to tell him – and as his adventurous lover who at one time entered into a threesome relationship with Auguste and his wife, Hilde. According to Claudia Pritchard, some of John’s letters were ‘partly modelled on the epistolary novels of… Samuel Richardson,’ novels which, we should note, are also psychologically searching in that the objectified ‘servant girl’ has agency through her letter-writing; and John greatly admired the interiors of Dutch painters and of Bonnard and Vuillard, ‘while largely resisting the ornamentation of their domestic scenes.’ Her preoccupation was with the subjective ‘life within,’ not the material surroundings. Given Rudolf’s acuity, his searching, informed preoccupation with the relationships of artist and models about whom he writes, and his unsentimental as well as unfailing awareness of how complex these can be, I wonder whether in any future consideration of Rego he will be prepared to give some space to John. I hope so. Judging from the story he has so far developed, whatever he has to say about her will be well worth reading. And it won’t need to take away from what is already a unique, invaluable account of key aspects of Paula Rego’s oeuvre.

Aug 5 2023

HOLDING A POSE

HOLDING A POSE: John Lucas comments on an intriguing essay by Anthony Rudolf on the role of the artist’s model

Now here’s an unlooked for treasure. Most of us in the literary world know of Anthony Rudolf as a fine poet who is also the publisher of Menard Books as well as a critic and biographer – in particular of a major work on Isaac Rosenberg. And some are aware that for many years he was the partner of the great artist, Paula Rego, for whom he often modelled. Now comes his account, not merely of their relationship as artist and sitter, but of the relationships between other artists and their models. The result is one of the most absorbing, suggestive and intellectually stimulating meditations I have read of what such relationships entail.

And then there is ‘Pauline.’ One of the most interesting of the several models about whom Rudolf writes, ‘Pauline’ frequently modelled for Degas, the ‘grumpy genius,’ as Rudolf calls that great artist. Part of her work was to humour Degas, to know when to change the subject of their talk, to console him ‘about his fading eyesight and troublesome bladder,’ and to advise him ‘not to wander around Paris alone.’ She sounds more of a matron than a mistress, and Degas’s relationship with her was certainly very different from the customary behaviour toward models of the predatory Puvis de Chavannes, although, Rudolf says, de Chavannes ‘seems to have been civilised with Susan Valadon, his close friend and nude model and lover, and mother of Maurice Utrillo (whose father may have been Puvis.)’ And if all this makes you feel a bit dizzy you can always murmur to yourself the words of the great Nancy Banks Smith when trying to recount the plot of an especially convoluted TV drama, ‘Oh, do keep up, Monica.’

But preferably you can consider the implications of Rudolf’s arresting remark that in thinking about the inter-subjectivity of painter and model, he finds himself reflecting on his position as Paula Rego’s model and how ‘I swivel my eyes and look at [her] out of curiosity and also with emotion: I and Thou, Thou and I, although I, her Thou am/is also an It… and one has no choice if Paula is to make the picture work.’ How strange, after all, to be both humanly engaged in the making of a painting and at the same time, reified by the artist/maker. Rudolf’s meditation puts me in mind of that moment in Our Mutual Friend when Bradley Headstone comes unexpectedly on the villainous Rogue Riderhood and thinks ‘Here is an instrument. Can I use it?’ Portraiture can’t but help being instrumental, a word the O.E.D. defines as ‘serving as an instrument or means to achieve a particular end or purpose.’ A model is often, perhaps usually, without agency. But not always. As Rudolf adds, ‘Posing for [Paula] is a pleasure and a privilege but there are moments when your mind wanders and your eye wanders and you wonder how long you can hold the pose without moving.’ The sentence fascinates me in the way it registers the model as a ‘you’, someone who is both the self and a not-self, who is an other, and there is also the intriguing ambiguity in that conscious punning (is it?) on wander/wonder. The mind is free to roam even as the body is held in place.

A different, but no less fascinating matter. Rudolf makes a persuasive case for one model being used in two very different paintings and of the peculiar effect this has on our reception of both. He is struck by the close resemblance between the face of General Miramon as depicted in Manet’s famous ‘Execution of Emperor Maximilian’ to that of the man in Henri Gervex’s ‘Rollo’ who stands, half-dressed, at the bedroom window of the room looking toward the bed where he and his lover have spent the night and where she now sprawls naked in satiated sleep. Not merely his face, with its distinctive moustache and beard, but his rumpled shirt, look very like that of the General’s. Rudolf tells us that the model for Miramon was Manet’s friend, the violinist, Damourette, which adds piquancy to the likelihood that the one man posed for both paintings. Delivering love to death wrapped in a rumpled sheet, you might say.

I have to admit that I am less interested in what Rudolf has to tell us about Rossetti and his models, Lizzie Siddal and Fanny Comforth, probably because the artist himself, however considerate he may have been to the various women in his life, seems to me less interesting, indeed on occasions (as in ‘Found’) verging on the incompetent. Look at the failure to control perspective in the drawing of the cart on which the netted ‘found’ lamb stands, how inexpert the use of colour – and anyway, how yukky the symbolism, how trite the moralising message of awakening conscience. It’s good to learn that Paula Rego’s favourite Pre-Raphaelite painter was Augustus Egg, who in many ways is hardly of the Brotherhood. Without having to give the thumbs-up to Rossetti, I can sympathise with Rudolf’s appreciative words about the Siddal and Comforth ‘Sisterhood.’

But far superior to either is Gwen John. If and when Rudolf develops his penetrative accounts of the models he writes about here, as he hints he will do, I hope he will have something to say about John, both as artist and model to Auguste Rodin, prepared to use her lithe body to adopt and maintain very demanding poses – ‘Je vain vous dormer des poses extraordinaire aussi Bien que les poses classiques, car je suis souple’ she wrote to tell him – and as his adventurous lover who at one time entered into a threesome relationship with Auguste and his wife, Hilde. According to Claudia Pritchard, some of John’s letters were ‘partly modelled on the epistolary novels of… Samuel Richardson,’ novels which, we should note, are also psychologically searching in that the objectified ‘servant girl’ has agency through her letter-writing; and John greatly admired the interiors of Dutch painters and of Bonnard and Vuillard, ‘while largely resisting the ornamentation of their domestic scenes.’ Her preoccupation was with the subjective ‘life within,’ not the material surroundings. Given Rudolf’s acuity, his searching, informed preoccupation with the relationships of artist and models about whom he writes, and his unsentimental as well as unfailing awareness of how complex these can be, I wonder whether in any future consideration of Rego he will be prepared to give some space to John. I hope so. Judging from the story he has so far developed, whatever he has to say about her will be well worth reading. And it won’t need to take away from what is already a unique, invaluable account of key aspects of Paula Rego’s oeuvre.