ARE YOU JUDGING ME YET?: Kate Noakes reviews an essay collection written by Kim Moore to accompany her own poetry

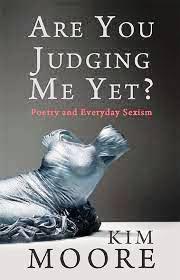

Are You Judging Me Yet?: Poetry and Everyday Sexism

Kim Moore

Seren

ISBN 9781781726877

£9.99

Are You Judging Me Yet?: Poetry and Everyday Sexism

Kim Moore

Seren

ISBN 9781781726877

£9.99

Are You Judging Me Yet? Well, this is a book review, so I sort of have to, but not in the way Kim Moore means in the title poem for her second collection. Halfway through, that poem disrupts itself with this question of judgement addressed to the reader/audience, and garners potentially upsetting reactions for Moore to explore. I read and admired Moore’s All the Men I Never Married (Seren, 2021) when it was first published, so it was with some relish that I turned the pages on this, its prose accompaniment. Here she sets out a number of essays derived from her PhD thesis. These serve as a reader’s guide to the poetry collection, as well as being well-researched pieces on sexism, feminist approaches, the male gaze, her personal experiences of sexism, her intentions in writing the poems and so on.

All these essays link back to and discuss the poems themselves, many of which are also included here. She explores her concerns and uncertainties in writing these poems, the varying responses she has had when performing them, and her development as a person and poet from undertaking this work. And she is innovative with her text. Prose and poems are organised such that the reader is given suggestions as to the order of reading. You can read linearly, but I chose to accept her challenge and read where her suggestions took me. ‘If you are unsure whether sexism exists turn to…If you would like to read about wilfulness turn to…If you would like to read a biography of violence…’ She even includes a handy checklist in the back so you can make sure you have, in fact, read the whole book. Only once did I find myself going around in a loop, which was easy to exit by simply reading on.

Moore relates a tale of being stuck in a train carriage with a man who just wants to talk, forcing her to put down the book she is reading – a key (and for her transformative) text by Adrienne Rich – as she cannot read it and has to listen to the man. ‘I don’t say anything because I don’t want to be rude.’ This perfectly articulates one of the traps we women find ourselves in. We silence ourselves and self-censor out of fear of what other people might think if we were to refuse or counter the position in which we are put. In my view, this is a misplaced sense of politesse. We are socialised to be polite. It is unladylike to be rude. But if you don’t say anything, are you participating in your abuse and objectification? This is one dilemma Moore explores. To speak out might be to put yourself at physical risk. But by remaining silent, you are putting yourself in psychological danger.

There are no easy answers here and I too have spent my whole life metaphorically biting my lip. What did happen as I read Moore’s book is that it reminded me of the great number of similar incidents from my own life. No doubt most women can also furnish their personal list. It was a triggering read in that regard, but this is no bad thing. It is as well to be reminded of the world be still live in, every, single, day. It also caused me to rethink a number of the feminist poems I have written, my motives, their cathartic effect, why I used to apologise to men in the audience when reading them, and the like.

I am a generation older than Moore, a so-called invisible woman, and it is depressing to realise from reading her book that nothing much has altered in (some) men’s treatment of women and in our ability to occupy public space and discourse. However some things have changed. Moore rightly points to #metoo and women speaking out as she herself does by means of this book and her poetry collection. To this extent her work is a kind of salve. We are not alone, there are others who know how it is (sadly) and are prepared to say something about it.

An interesting poem about women, ‘We are Coming’, moves away from the numbered men poems and includes this: ‘We are arriving from the narrow places,/ from the spaces we are given’ and in the penultimate line ‘our bodies saying no, we were not born for this.’ I wish Moore had been able to title the poem ‘We are already here’ or ‘We’ve been here all along’. Perhaps that is one my granddaughter will write; but then again hopefully it is one she will not need to.

If you haven’t read a feminist analysis for a while, if you’ve never read one, if you don’t think you need to read one, then do, please read this. Moore is a good place to start and revisit and there are many writers to follow up on from her careful research. You won’t be disappointed.

Towards the end of the book Moore describes another train journey on which she is told by the conductor to smile. She responds by baring her teeth, and a few moments later points out to the conductor that he hasn’t told a nearby man to smile. She is speaking out and smiling to herself. Brava!

Aug 17 2023

Are You Judging Me Yet?

ARE YOU JUDGING ME YET?: Kate Noakes reviews an essay collection written by Kim Moore to accompany her own poetry

Are You Judging Me Yet? Well, this is a book review, so I sort of have to, but not in the way Kim Moore means in the title poem for her second collection. Halfway through, that poem disrupts itself with this question of judgement addressed to the reader/audience, and garners potentially upsetting reactions for Moore to explore. I read and admired Moore’s All the Men I Never Married (Seren, 2021) when it was first published, so it was with some relish that I turned the pages on this, its prose accompaniment. Here she sets out a number of essays derived from her PhD thesis. These serve as a reader’s guide to the poetry collection, as well as being well-researched pieces on sexism, feminist approaches, the male gaze, her personal experiences of sexism, her intentions in writing the poems and so on.

All these essays link back to and discuss the poems themselves, many of which are also included here. She explores her concerns and uncertainties in writing these poems, the varying responses she has had when performing them, and her development as a person and poet from undertaking this work. And she is innovative with her text. Prose and poems are organised such that the reader is given suggestions as to the order of reading. You can read linearly, but I chose to accept her challenge and read where her suggestions took me. ‘If you are unsure whether sexism exists turn to…If you would like to read about wilfulness turn to…If you would like to read a biography of violence…’ She even includes a handy checklist in the back so you can make sure you have, in fact, read the whole book. Only once did I find myself going around in a loop, which was easy to exit by simply reading on.

Moore relates a tale of being stuck in a train carriage with a man who just wants to talk, forcing her to put down the book she is reading – a key (and for her transformative) text by Adrienne Rich – as she cannot read it and has to listen to the man. ‘I don’t say anything because I don’t want to be rude.’ This perfectly articulates one of the traps we women find ourselves in. We silence ourselves and self-censor out of fear of what other people might think if we were to refuse or counter the position in which we are put. In my view, this is a misplaced sense of politesse. We are socialised to be polite. It is unladylike to be rude. But if you don’t say anything, are you participating in your abuse and objectification? This is one dilemma Moore explores. To speak out might be to put yourself at physical risk. But by remaining silent, you are putting yourself in psychological danger.

There are no easy answers here and I too have spent my whole life metaphorically biting my lip. What did happen as I read Moore’s book is that it reminded me of the great number of similar incidents from my own life. No doubt most women can also furnish their personal list. It was a triggering read in that regard, but this is no bad thing. It is as well to be reminded of the world be still live in, every, single, day. It also caused me to rethink a number of the feminist poems I have written, my motives, their cathartic effect, why I used to apologise to men in the audience when reading them, and the like.

I am a generation older than Moore, a so-called invisible woman, and it is depressing to realise from reading her book that nothing much has altered in (some) men’s treatment of women and in our ability to occupy public space and discourse. However some things have changed. Moore rightly points to #metoo and women speaking out as she herself does by means of this book and her poetry collection. To this extent her work is a kind of salve. We are not alone, there are others who know how it is (sadly) and are prepared to say something about it.

An interesting poem about women, ‘We are Coming’, moves away from the numbered men poems and includes this: ‘We are arriving from the narrow places,/ from the spaces we are given’ and in the penultimate line ‘our bodies saying no, we were not born for this.’ I wish Moore had been able to title the poem ‘We are already here’ or ‘We’ve been here all along’. Perhaps that is one my granddaughter will write; but then again hopefully it is one she will not need to.

If you haven’t read a feminist analysis for a while, if you’ve never read one, if you don’t think you need to read one, then do, please read this. Moore is a good place to start and revisit and there are many writers to follow up on from her careful research. You won’t be disappointed.

Towards the end of the book Moore describes another train journey on which she is told by the conductor to smile. She responds by baring her teeth, and a few moments later points out to the conductor that he hasn’t told a nearby man to smile. She is speaking out and smiling to herself. Brava!