Jul 24 2023

Words & Pictures

WORDS & PICTURES: Thomas Ovans views some intriguing video poems created by Rosemary Norman and Stuart Pound

Words & Pictures Rosemary Norman & Stuart Pound Aspect Ratio (2 Lothair Road, London W5 4TA) ISBN 978-1-3999-4822-7 £8.50

Many readers will have seen and enjoyed Rosemary Norman’s poems in magazines and also observed that her bio note mentions her collaborations with video artist Stuart Pound in the making of poetry videos. These videos have been shown at festivals and other film events (including some at the BFI); but the majority of Norman’s readers will probably not have had a chance to attend one of these screenings. Fortunately it is now possible to experience a selection of Norman & Pound’s work in the comfort of one’s own home. A new book Words & Pictures contains 18 of Norman’s poems together with a number of stills from the corresponding videos and, more importantly, an internet link / QR code giving access to an on-line archive where the videos can be seen in full. This offers a simple but satisfying multi-media experience where one can enjoy the words on the page alongside (or as a curtain-raiser to) a visual and auditory interpretation.

Most of the poems in Words & Pictures have appeared in Norman’s previous collections but this is not really a drawback because the whole point is to present them in a new way that was not previously available. The video responses are of many different kinds: some are straightforward illustrations of the subject matter; in others the poem text itself appears on screen and undergoes various kinds of graphic manipulation; and a third group use found images – details from photographs or paintings – and a musical soundtrack to counterpoint the reading of the poem. All the videos are quite short – typically between one and a half and two and a half minutes – and the reading of the poem may occupy only about half the total running time. In most cases the voice we hear is Rosemary Norman’s but Stuart Pound does feature as narrator on two occasions.

[Editor’s note: In fact all readings are by Rosemary Norman but her voice is sometimes slowed down which accounts for our reviewer’s belief that he was hearing Stuart Pound.]

The book opens with a fanciful poem about floods in Paris in the early twentieth century (“1910”) and reports that ‘street lamps/ fell in love with their own // ornate reflections in the rising water.’ The video uses black and white contemporary postcard photos to show Parisians coping with the rising water by crossing flooded streets on rickety trestle bridges and even on rows of chairs.

The second poem “Alarm” is a more imaginative and begins rather like a piece of speculative fiction

I knew a woman once who wrote me letters so wide open with love I swear I smelt it.

(However a note with the video suggests that the poem is at least partly factual and is based on an item in a French newspaper.) In the video Norman’s voice is heard reading the strange story against a background of moving lights, perhaps suggesting a swarm of slowly dancing fireflies, which generates a suitably mysterious atmosphere.

After “The Angry Sleeper”, a ‘not-quite-serious animated nightmare’ illustrated by details from a Dirk Bouts painting of demons carrying their victims off into hell, we are probably ready for a change of mood! The sound track for “Aviatrix” is a jaunty 1920s style melody and the images make clear that the poem is in the voice of Amy Johnson (who made a record-breaking solo flight to Australia in May 1930). There is in fact a tension between the cheerful music and the reflective tone of the poem – ‘You can’t argue with the wind / up here. It’s solid’ – as we hear Johnson considering her brief time of fame and seeming also to foresee her own death (which occurred in a flying accident in 1941). The video presents the poem twice. We first hear Norman reading it and then we are shown the words scrolling past with key words highlighted in red – a simple but effective reprise.

The first video to use only the poem’s words is “Exposure”. This is a completely silent film in which the text appears in white on black and seems to swim up, like writhing ghostly shapes, from deep darkness, taking several seconds to resolve itself into stanzas of the poem. This noiseless emergence of a narrative is very suitable since the poem tells a true story of a young stowaway who fell silently from an airliner flying over Kew on approach to Heathrow airport.

The videos which play with text are, for me, among the most successful. In “Writing Behaviour” (which is based upon observations made in a psychiatric hospital) the opening lines of the poem appear on screen almost grudgingly as if dragging their feet. This reluctance is well matched by a jangling and sometimes discordant piano sound track. In the later stages, the lines arrive in a more chaotic way as huge gothic letters which tumble onto the viewing plane and make sense only when they have shrunk to normal size. Another satisfying example is “Simple Simple Simple” which is a poem constructed using only words from the last paragraph of Alice in Wonderland. The video gives us time to read that last paragraph and then we watch the words disappear one by one as we hear the poem spoken.

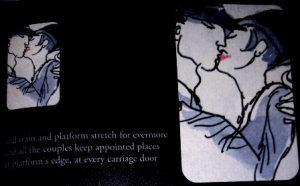

Instead of manipulating text, the video “Kissing in Hats” plays with the sound of the words as Norman reads the poem twice, but with a fraction of a second lag, so that every word is followed by an almost immediate echo. The poem is a villanelle so the delayed double-tracking complements the repetition which is an essential part of the composition. Norman’s poetry is often rather enigmatic but in this case she gives a transparent and movingly descriptive response to a scene in a 1940s railway station:

Kissing in hats before they go to war – the angle of the brims the tilted faces the platform’s edge, the open carriage door

There are about ten more videos for readers to discover for themselves if they seek out their own copy of Words & Pictures – a course of action which I warmly recommend. The combination of video and text offers a novel way of consuming poetry. I found it easy to access the website where the videos reside (but, oddly, not in the same order as the poems appear in the text). Once the videos have been located one might choose to read each poem from the page before playing the video. On the other hand, readers may like to have the book open to glance at even while the video is running. This second method provides a useful fallback in a couple of cases when – on my venerable laptop at least – the spoken words don’t quite hold their own against a music track.

Symphony Jane by Rosemary Norman | Moving Poems

21/04/2024 @ 15:18

[…] Last year, Pound and Norman came out with a print book showcasing their collaborations, Words & Pictures, available from Aspect Ratio (2 Lothair Road, London W5 4TA) for £8.50, which garnered a good review in London Grip: […]