Poetry review – FIVE FIFTY-FIVE: Edmund Prestwich finds many reasons to admire Maura Dooley’s collection

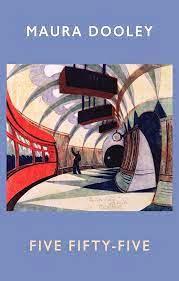

Five Fifty-Five

Maura Dooley

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN978-1-78037-657-8

£10.99

Five Fifty-Five

Maura Dooley

Bloodaxe Books

ISBN978-1-78037-657-8

£10.99

What most struck me about Maura Dooley’s Five Fifty-Five was how vividly the poems embody sensations and ideas and how delicately they extend them. Metaphor plays a crucial role. Sometimes it comes as a single brilliant flash, as in ‘Gaudy Welsh’ with

As if the sturdy sweetness of a jug of cream

had burst into song;

Often there’s a more extended development. ‘Vertaling’ (the Dutch word for ‘translation’) begins

I struggle to balance your words on a silver tray.

They tinkle. I fear for a smash and splinters.

Shuffling along trying to match the spring in your step

all the time looking up, keeping my head in the air,

I have filled each one with a drop of something.

This is more than merely graphic. We don’t just see the picture, we inhabit it in an almost kinaesthetic way, feeling in our bodies something of the muscular processes involves in the movements and effort it describes. This is where Dooley’s other great gift comes in – her ability to create rhythms that combine tensile strength with unpredictable elements that work expressively to emphasise swerves in thought or to mime what is being described. This seems to me particularly evident in the sentence beginning ‘Shuffling along’, where the delaying of the main clause by line four and a stanza gap create a sensation analogous to the precarious effort of balancing a tray of wobbly glassware. Taking off from the etymology of ‘translation’ – from Latin words meaning ‘carrying across’ – Dooley’s lines make an arresting mental image of the difficulties and inevitably only partial success of transferring a poem from one language to another. The poem presents this as an offering from poet to original writer: ‘Shyly, I raise my tray to you. An offering on tin’. But by this end point in the poem, ‘you’ embraces the reader too. Dooley offers her translation both to the original poet and to its new English audience. And beyond its specific application to translation, the ripples of suggestion spreading from ‘Vertaling’ evoke any artist’s effort to carry her own meanings into another mind. In ‘UnEnglished’, Dooley describes how an encounter with another foreign language, Welsh in this case, brings the speaker an intense sensuous joy expressed by images of smelling a succulent dish being cooked. And when she says ‘I knock at the door of this language’, she hints that learning a new language opens a new world and transforms one’s sense of reality.

This leads me to another feature of the book: Dooley’s alert, generous interest in how others see and express the world. This is reflected in the familiar way in which a number of these poems refer to other writers or texts or draw inspiration from works of art. There’s nothing academic about such references as Dooley handles them. Allusions are introduced with a naturalness that shows how fully things Dooley has read or seen have been absorbed into her feeling for life. What’s involved may be high art or may be something remembered from the nursery; both are equally food for the mind. Nothing is compartmentalized. And because nothing is compartmentalized, reflections on social and political concerns gain subtlety and depth from being interwoven with reflections of a more quietly personal kind. Both ‘The Blue Willow and the Indian Tree’ and ‘The Forests of South London’ celebrate migration and cultural transfusion by quietly reminding the reader how much of our civic and domestic life draws on influences from abroad. One of the ecological poems, ‘A-Sighing-and-a-Sobbing’, takes its title from the nursery rhyme ‘Who Killed Cock Robin’. Its dominant feeling is one of elegiac sorrow at our loss of birds, ‘old friends’ whose ‘flicker or flash / once lit field and bush’. However, the concluding plea, ‘find us again in our bankruptcy, / feather our nest’, disturbs this tone with a hint of more savage self-blame. ‘Feather our nest’ clashes the idea of the naturally nurturing softness of a bird’s nest against that of financial sharp practice. The answer to the implied question ‘who killed all these birds’ is that we did with our greedy short-sightedness. But for me the beauty of the poem is that instead of simply denouncing short-sightedness and greed, its elegiac tone gently invites us to come to our senses before it’s too late.

The suggestiveness of the poems and the contribution of allusion can be very oblique and as it were tentative. ‘Her Wish for Big Windows’ is a beautiful piece about embracing life with gusto, written with an energy of language befitting its theme. The last four lines seem to me to draw depth of resonance from the memory of Catullus’s famous fifth ode, particularly from the lines translated by Ben Jonson as

Suns, that set, may rise again:

But if once we lose this light,

'Tis, with us, perpetual night

I’m not suggesting, of course, that only the thought of Catullus’s poem would lead one to see a hint of the inevitability of death in the first two lines of Dooley’s concluding stanza:

never mind the long shady season that is to come,

the shortness of days that no clock can turn back,

However, I do think that putting the two together in one’s mind helps one appreciate more fully the positive spirit in which Dooley embraces mortality and see how utterly she has remade Catullus’s idea in terms of her own sensibility:

each casement, every sash will open wide in that house

the brilliant air will bathe and soothe her smiling, waiting face.

(An important qualification is that this final stanza is not offered as first a command and then a prophecy made by the poet herself but as what the unspecified third person who wishes for big windows thinks.) I said that ‘UnEnglished’ hints at language’s power not merely to represent the world, but to heighten and transform our perceptions of it. That poem is about the transforming power of seeing things in terms of another language but I feel that the special gift of all the writing in Five Fifty-Five is to refresh and heighten our perceptions. Dooley’s talent for metaphor gives her writing imaginative drive in a very obvious way. More elusively, her poetry’s enchanting of the world depends on an indefinable rightness, beauty, evocativeness in the very sound and flow of her lines, and on her tact in surrounding words with pauses and breathing spaces within which the reader’s own thoughts can grow. I’m aware here of talking about something that is not susceptible of analysis. Other people will either spontaneously share such an impression or will dismiss it as a hopelessly subjective response on my part. But it’s so important to my enjoyment of these poems that I want to put it on record.

This sensitive feeling for words lies behind the outstanding success of Dooley’s haiku and haiku-inflected short poems, both those in response to Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji and her translations of the contemporary haiku poet Yasouaki Inoue. Even more outstanding, to my mind, is the tiny ‘Autumn in the Absent Elms’, presumably referring to the devastating impact of Dutch elm disease, but, again, with ripples that spread almost infinitely beyond the particular case and even beyond the wider ecological theme it implies. The poem is prefaced by a line from Gerard Manley Hopkins’s ‘Binsey Poplars’ – ‘After-comers cannot guess the beauty been’. For those who remember that piece, Hopkins’s lines

O if we but knew what we do

When we delve or hew —

Hack and rack the growing green!

pull the poem into the orbit of particular grief at man’s environmental destructiveness, but Dooley lets that sound as just one note among many others. Her whole poem goes

Their soft green bells toll unheard

mist moist frost last lost

Jun 30 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Maura Dooley

Poetry review – FIVE FIFTY-FIVE: Edmund Prestwich finds many reasons to admire Maura Dooley’s collection

What most struck me about Maura Dooley’s Five Fifty-Five was how vividly the poems embody sensations and ideas and how delicately they extend them. Metaphor plays a crucial role. Sometimes it comes as a single brilliant flash, as in ‘Gaudy Welsh’ with

Often there’s a more extended development. ‘Vertaling’ (the Dutch word for ‘translation’) begins

This is more than merely graphic. We don’t just see the picture, we inhabit it in an almost kinaesthetic way, feeling in our bodies something of the muscular processes involves in the movements and effort it describes. This is where Dooley’s other great gift comes in – her ability to create rhythms that combine tensile strength with unpredictable elements that work expressively to emphasise swerves in thought or to mime what is being described. This seems to me particularly evident in the sentence beginning ‘Shuffling along’, where the delaying of the main clause by line four and a stanza gap create a sensation analogous to the precarious effort of balancing a tray of wobbly glassware. Taking off from the etymology of ‘translation’ – from Latin words meaning ‘carrying across’ – Dooley’s lines make an arresting mental image of the difficulties and inevitably only partial success of transferring a poem from one language to another. The poem presents this as an offering from poet to original writer: ‘Shyly, I raise my tray to you. An offering on tin’. But by this end point in the poem, ‘you’ embraces the reader too. Dooley offers her translation both to the original poet and to its new English audience. And beyond its specific application to translation, the ripples of suggestion spreading from ‘Vertaling’ evoke any artist’s effort to carry her own meanings into another mind. In ‘UnEnglished’, Dooley describes how an encounter with another foreign language, Welsh in this case, brings the speaker an intense sensuous joy expressed by images of smelling a succulent dish being cooked. And when she says ‘I knock at the door of this language’, she hints that learning a new language opens a new world and transforms one’s sense of reality.

This leads me to another feature of the book: Dooley’s alert, generous interest in how others see and express the world. This is reflected in the familiar way in which a number of these poems refer to other writers or texts or draw inspiration from works of art. There’s nothing academic about such references as Dooley handles them. Allusions are introduced with a naturalness that shows how fully things Dooley has read or seen have been absorbed into her feeling for life. What’s involved may be high art or may be something remembered from the nursery; both are equally food for the mind. Nothing is compartmentalized. And because nothing is compartmentalized, reflections on social and political concerns gain subtlety and depth from being interwoven with reflections of a more quietly personal kind. Both ‘The Blue Willow and the Indian Tree’ and ‘The Forests of South London’ celebrate migration and cultural transfusion by quietly reminding the reader how much of our civic and domestic life draws on influences from abroad. One of the ecological poems, ‘A-Sighing-and-a-Sobbing’, takes its title from the nursery rhyme ‘Who Killed Cock Robin’. Its dominant feeling is one of elegiac sorrow at our loss of birds, ‘old friends’ whose ‘flicker or flash / once lit field and bush’. However, the concluding plea, ‘find us again in our bankruptcy, / feather our nest’, disturbs this tone with a hint of more savage self-blame. ‘Feather our nest’ clashes the idea of the naturally nurturing softness of a bird’s nest against that of financial sharp practice. The answer to the implied question ‘who killed all these birds’ is that we did with our greedy short-sightedness. But for me the beauty of the poem is that instead of simply denouncing short-sightedness and greed, its elegiac tone gently invites us to come to our senses before it’s too late.

The suggestiveness of the poems and the contribution of allusion can be very oblique and as it were tentative. ‘Her Wish for Big Windows’ is a beautiful piece about embracing life with gusto, written with an energy of language befitting its theme. The last four lines seem to me to draw depth of resonance from the memory of Catullus’s famous fifth ode, particularly from the lines translated by Ben Jonson as

I’m not suggesting, of course, that only the thought of Catullus’s poem would lead one to see a hint of the inevitability of death in the first two lines of Dooley’s concluding stanza:

However, I do think that putting the two together in one’s mind helps one appreciate more fully the positive spirit in which Dooley embraces mortality and see how utterly she has remade Catullus’s idea in terms of her own sensibility:

(An important qualification is that this final stanza is not offered as first a command and then a prophecy made by the poet herself but as what the unspecified third person who wishes for big windows thinks.) I said that ‘UnEnglished’ hints at language’s power not merely to represent the world, but to heighten and transform our perceptions of it. That poem is about the transforming power of seeing things in terms of another language but I feel that the special gift of all the writing in Five Fifty-Five is to refresh and heighten our perceptions. Dooley’s talent for metaphor gives her writing imaginative drive in a very obvious way. More elusively, her poetry’s enchanting of the world depends on an indefinable rightness, beauty, evocativeness in the very sound and flow of her lines, and on her tact in surrounding words with pauses and breathing spaces within which the reader’s own thoughts can grow. I’m aware here of talking about something that is not susceptible of analysis. Other people will either spontaneously share such an impression or will dismiss it as a hopelessly subjective response on my part. But it’s so important to my enjoyment of these poems that I want to put it on record.

This sensitive feeling for words lies behind the outstanding success of Dooley’s haiku and haiku-inflected short poems, both those in response to Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji and her translations of the contemporary haiku poet Yasouaki Inoue. Even more outstanding, to my mind, is the tiny ‘Autumn in the Absent Elms’, presumably referring to the devastating impact of Dutch elm disease, but, again, with ripples that spread almost infinitely beyond the particular case and even beyond the wider ecological theme it implies. The poem is prefaced by a line from Gerard Manley Hopkins’s ‘Binsey Poplars’ – ‘After-comers cannot guess the beauty been’. For those who remember that piece, Hopkins’s lines

O if we but knew what we do When we delve or hew — Hack and rack the growing green!pull the poem into the orbit of particular grief at man’s environmental destructiveness, but Dooley lets that sound as just one note among many others. Her whole poem goes