Poetry review – THE INTERPRETATION OF OWLS: John Forth enjoys an immersion in a substantial and very well curated selection from John Greening’s work

The Interpretation of Owls - Selected Poems 1977- 2022

John Greening

Baylor University Press

ISBN 9781481317344

478pp £20.00

The Interpretation of Owls - Selected Poems 1977- 2022

John Greening

Baylor University Press

ISBN 9781481317344

478pp £20.00

A first look into any book, especially a big one, can feel like gazing into an orchard. The straight lines turn out to be densely tangled when you drop your speed, and it’s natural that the ripest fruit will entice. In the midst of it all, a blackbird ‘pecks all the eaters / and sings’. So began John Greening’s enormous harvest in a poem dated 1977, five years before his first collection, appearing only in Bananas (1979) and, henceforth, nowhere but here. It’s tucked in by Kevin Gardner as the grand opening of the final section: INTIMATIONS. Edited in consultation with the poet, this first American collection presents a poetic journey of more than forty years, and it is exceedingly well-travelled. Arranged in sections to illustrate abiding interests and influences, the book comprises nearly 300 poems from twenty-two collections by eighteen publishers, and also previously uncollected and unpublished work. The use of thematic ordering surfaced strongly but not exclusively in Hunts (2009) but for readers who prefer to have the option of reading poems in order of original publication there’s also a chronological table of contents – offering more than one route through an orchard – an author’s preface, editor’s introduction, two indexes and an interview with the poet in which he discusses the background to some of his work. A review such as this can only hope to focus on examples that may shed light on some of Greening’s stop-overs.

This is his third ‘selected’. The first, Nightflights (Rockingham 1998), was in part also a new collection of thirty-eight poems; the second, Hunts (Greenwich Exchange, 2009) covers just under half the number of collections in this new volume but also includes some 50 or so hitherto uncollected pieces (a few of which re-appear here). Of two Arvon Competition sequences in ‘Hunts’, Fotheringhay makes the cut here, but not Coastal Path. The poet tells us that three-quarters of the poems in ‘Owls’ did not appear in ‘Hunts’, all of which signals an extraordinary work-ethic and a preference for using the new vehicle to try out current work. Nearly all of 120 uncollected/unpublished poems have been written in the twenty-first century and about 40 since his last ‘major’ collection in 2019. Even at 478 pages we are still very much in the grip of ‘a Selected’, which some might have called a ‘New & Selected’.

The 60 ‘uncollected’ comprise a solid gathering of work that has been visible but not included in his twenty or so full collections. To counter-balance this, another almost identically career-spanning selection presents work that hasn’t appeared anywhere until now, much of it recent. Even so, I couldn’t resist beginning near the end of this book, with his first published piece The Orchard (1977) in which we were carefully prepared for what was to follow:

The monodic trunk

breaks into couples half as strong

and into families and relationships

weakening into stick-orgies

and twigs

so high they snap.

This is the logical consequence

of the binary system

where the choice is yes or no.

If it resembles operations inside a machine or a huge body of selected poems, we’ve already had a tip-off that the metaphor is reaching further:

...the details of the action

are a progression of doubt,

faith into doubt.

I began in wonder that a 23 year-old could be so much at ease when confronted by an age of so-called certainties, and Greening admits that maybe he should have trusted his young self more. Even Ted Hughes expressed an interest and offered encouragement. Twenty years later, another uncollected gem, To Icarus (Acumen, 1997) would demonstrate how adept he became at using various personae. More mischief, and very funny:

...This is not poetry, but science…

Have confidence in me. You know all flight

is binary, a balance held between

the earth’s pull and the air…

My only fear is of your fearfulness.

You never rushed to be the first one down

a slide…

The poem is a joyful celebration of a personality type – of one who says what he likes and likes what he says – one of dozens of manipulations of characters from history and myth. The unpublished poem Flight (2015) gives the section its title and is a beautiful pondering of planes, herons and essentially an osprey to build a complex response to nostalgia and distance. In the section labelled WORDS a brief tribute to Sylvia Plath on the fiftieth anniversary of her death tells us that ‘Those who were born that day // are announcing their half century / on Facebook, a blue plaque / in the cloud.’ The poem skillfully sets powerful and trivial side- by-side, as if they’ve always appeared that way:

...One year in ten

there’s such a winter: warm yourself

at the editorial bonfire, watch

the dying art of hedging

and ditching, forgive the crystal

deceptions, and let Ariel go.

(Unpublished, 2013)

A solemn mood dominates a pair of poems written two years apart in 2016 and 2018. In the first, a search for a colleague’s grave in Pendragon country prompts an epiphany in which ‘I perch / in drizzle on a name that’s worn away…

holding The Parish of Tintagel, Some

Historical Notes, forgetful of my reasons

and all distance. ‘Preparation for death’

I want to say when they ask what poetry is

then find their tongues becoming Cornish slate

and every scratch or squeak an elegy.

(After a Poetry Workshop, 2016)

One of the Huntingdonshire Codices (which we can hope to see soon in their entirety) at the moment lives only in an edition of ‘Poetry Review’ (2018), a meticulous terza rhyma which opens with the challenging line ‘You have to be a bit unbalanced to write’ and proceeds to base its lessons on natural phenomena:

The waters, muddy, persistent, irresistible, hold

your life beneath the surface and will soon have sold

you down the river if you don’t reach out for a reed,

a straw, an overhanging rush, a feather, tread

water and pull yourself up word by word.

(Ars Poetica, 2018)

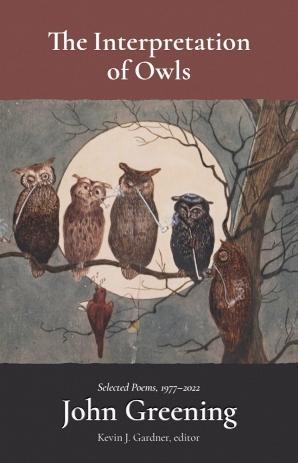

Finally the title poem The Interpretation of Owls gives prominence to a recent magazine piece published in Ink, Sweat & Tears (2021) in response to one of his grandfather’s caricatures dating from 1901, which is also featured on the front cover and as a frontispiece. It’s a mischievous poem, in that five owls are listening to a nightingale: ‘Our tree may be scarred / but that young flapper sings’. The author’s gloss compares the owls to ‘five patients waiting for wise Dr. Freud’. It is a clever conceit. Each owl speaks in turn and the fifth will put us in mind of a bird singing of what’s past, passing or to come – because (with no space on the main branch) it is therefore able to see clearly:

...the launch

of a future into your blue

unknowing. Of all that’s yet

to come. To it. To you.

This is a fine example of what might almost be a Greening stock-in-trade. A more or less promising trigger is transformed into something playfully, often outlandishly, disturbing. Apparently, if the date is accurate, his grandfather would have been fifteen. I stand by ‘mischievous’, but it’s also somewhat chilling.

The opening section, PILGRIM, presents a challenged, even sardonic narrator playing against or within a theme, predominantly twenty-first century and leaning toward glimpses of enlightenment. From the Greening family home he could cycle to Molesworth or Little Gidding, so you’d expect him to emerge looking both ways. Or more likely three at somewhere like The Triangular Lodge near Rushton, Northants. It will not give up its secrets, not to Elizabeth’s spymasters nor to archaeological poets. Its surroundings seem strangely non-committal: ‘The intercity passes it, so does the road / to Rushton.’ A poet of place who so truly inhabits his subjects is quite rare I think. But whatever else Thomas Tresham’s famous token of resistance does, it will always resist.

...There is an odd

sensation of being at both the hub and the rim,

that something spinning fast speeds you ahead

while something else is still and shaded, firm.

It seems that Catholic Tresham’s ‘brick equation’ was never fully solved. The Tudor thought-police didn’t like it, but they couldn’t do him for it. Despite living close by for many years, even John Greening couldn’t get a tune out of it until 2021. That’s how resistant the place is. Similarly, there can be few of us who won’t have arrived At Little Gidding to find not much going on, but this deft-handed investigator puts it to use in a gentle parody of Larkin, complete with cycle-clips (Huntingdonshire Elegies, 2009). The whole collection is book-ended by Huntingdonshire Psalmody (Long Poem Magazine, 2017) and a lock-down piece entitled Aufklärung or ‘enlightenment’(Hudson Review, 2022). The former is an unashamedly nostalgic walk from skylarks to solar farm, uniting personal and universal contexts with a combination of intense sadness and forlorn hope. Some freedom of passage has been lost while a boundary is being regained because ‘someone is troubling to set…

...a proper layered hedge on the ridge

between Huntingdonshire and Bedfordshire…

...The lost language of pleaching.

Someone has something to say for the land.’

Aufklärung is given a composition date of May, 2020 and is the most direct poem I’ve seen tackling the contradictory elements of lockdown. Its 104 hexameters in rhymed couplets defy brief quotation and uniquely capture an interwovenness of the time: ‘You are the mariner who knows he’s been / aboard the Marie Celeste and lived…’ There’s more than a little emotional loading when, after a so-called drumroll crescendo, it ends ironically: ‘You can disappear’.

And so to the editing. It is both joy and jolt to be confronted by eleven ‘mini-selecteds’ of thirty-odd pages organised by theme. Surprises and new relationships between poems abound. A transformative selection has much in common with a decluttered house, where stuff is lost and gained. It looks great, may even look ‘lived in’ – but where’s that gift you swore by? The homely sprawl of ‘Huntingdonshire Eclogues’, 32 poems in ‘Fotheringhay’ (1995) became 6 in ‘Nightflights’ (1998) and 21 in ‘Hunts’ (2009) but only creeps in here as Three Eclogues (‘Home’ section) plus two separate renamed poems: Airfields & Power Lines (‘Flight’ and ‘Intimations’ – two among several sections tight enough to entice yet loose enough to risk appearing random). Understandable given the enormity of choice, but I hope it’s for the shop window display and not a precursor to chipping away bits of the edifice. It may be tidy, and the assured poet may have fingers itching to tweak parts of the building, but the homely tercets of hexameters means they’ll stand apart wherever they’re placed, and there will always be reasons for keeping them together. That said, this collection lays down a challenge for all young poets approaching their seventies: how to be more profound, allusive and observant whilst also prolific and user-friendly. I struggle to grasp how he’s doing it, but I can see it’s being done. I’d want this book even if I owned the other two. It’s a treasure, hopefully to boost bucks and fame across the pond for one of our best, brightest and busiest poets of the last forty-odd years.

Jun 25 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – John Greening

Poetry review – THE INTERPRETATION OF OWLS: John Forth enjoys an immersion in a substantial and very well curated selection from John Greening’s work

A first look into any book, especially a big one, can feel like gazing into an orchard. The straight lines turn out to be densely tangled when you drop your speed, and it’s natural that the ripest fruit will entice. In the midst of it all, a blackbird ‘pecks all the eaters / and sings’. So began John Greening’s enormous harvest in a poem dated 1977, five years before his first collection, appearing only in Bananas (1979) and, henceforth, nowhere but here. It’s tucked in by Kevin Gardner as the grand opening of the final section: INTIMATIONS. Edited in consultation with the poet, this first American collection presents a poetic journey of more than forty years, and it is exceedingly well-travelled. Arranged in sections to illustrate abiding interests and influences, the book comprises nearly 300 poems from twenty-two collections by eighteen publishers, and also previously uncollected and unpublished work. The use of thematic ordering surfaced strongly but not exclusively in Hunts (2009) but for readers who prefer to have the option of reading poems in order of original publication there’s also a chronological table of contents – offering more than one route through an orchard – an author’s preface, editor’s introduction, two indexes and an interview with the poet in which he discusses the background to some of his work. A review such as this can only hope to focus on examples that may shed light on some of Greening’s stop-overs.

This is his third ‘selected’. The first, Nightflights (Rockingham 1998), was in part also a new collection of thirty-eight poems; the second, Hunts (Greenwich Exchange, 2009) covers just under half the number of collections in this new volume but also includes some 50 or so hitherto uncollected pieces (a few of which re-appear here). Of two Arvon Competition sequences in ‘Hunts’, Fotheringhay makes the cut here, but not Coastal Path. The poet tells us that three-quarters of the poems in ‘Owls’ did not appear in ‘Hunts’, all of which signals an extraordinary work-ethic and a preference for using the new vehicle to try out current work. Nearly all of 120 uncollected/unpublished poems have been written in the twenty-first century and about 40 since his last ‘major’ collection in 2019. Even at 478 pages we are still very much in the grip of ‘a Selected’, which some might have called a ‘New & Selected’.

The 60 ‘uncollected’ comprise a solid gathering of work that has been visible but not included in his twenty or so full collections. To counter-balance this, another almost identically career-spanning selection presents work that hasn’t appeared anywhere until now, much of it recent. Even so, I couldn’t resist beginning near the end of this book, with his first published piece The Orchard (1977) in which we were carefully prepared for what was to follow:

If it resembles operations inside a machine or a huge body of selected poems, we’ve already had a tip-off that the metaphor is reaching further:

I began in wonder that a 23 year-old could be so much at ease when confronted by an age of so-called certainties, and Greening admits that maybe he should have trusted his young self more. Even Ted Hughes expressed an interest and offered encouragement. Twenty years later, another uncollected gem, To Icarus (Acumen, 1997) would demonstrate how adept he became at using various personae. More mischief, and very funny:

The poem is a joyful celebration of a personality type – of one who says what he likes and likes what he says – one of dozens of manipulations of characters from history and myth. The unpublished poem Flight (2015) gives the section its title and is a beautiful pondering of planes, herons and essentially an osprey to build a complex response to nostalgia and distance. In the section labelled WORDS a brief tribute to Sylvia Plath on the fiftieth anniversary of her death tells us that ‘Those who were born that day // are announcing their half century / on Facebook, a blue plaque / in the cloud.’ The poem skillfully sets powerful and trivial side- by-side, as if they’ve always appeared that way:

...One year in ten there’s such a winter: warm yourself at the editorial bonfire, watch the dying art of hedging and ditching, forgive the crystal deceptions, and let Ariel go. (Unpublished, 2013)A solemn mood dominates a pair of poems written two years apart in 2016 and 2018. In the first, a search for a colleague’s grave in Pendragon country prompts an epiphany in which ‘I perch / in drizzle on a name that’s worn away…

holding The Parish of Tintagel, Some Historical Notes, forgetful of my reasons and all distance. ‘Preparation for death’ I want to say when they ask what poetry is then find their tongues becoming Cornish slate and every scratch or squeak an elegy. (After a Poetry Workshop, 2016)One of the Huntingdonshire Codices (which we can hope to see soon in their entirety) at the moment lives only in an edition of ‘Poetry Review’ (2018), a meticulous terza rhyma which opens with the challenging line ‘You have to be a bit unbalanced to write’ and proceeds to base its lessons on natural phenomena:

The waters, muddy, persistent, irresistible, hold your life beneath the surface and will soon have sold you down the river if you don’t reach out for a reed, a straw, an overhanging rush, a feather, tread water and pull yourself up word by word. (Ars Poetica, 2018)Finally the title poem The Interpretation of Owls gives prominence to a recent magazine piece published in Ink, Sweat & Tears (2021) in response to one of his grandfather’s caricatures dating from 1901, which is also featured on the front cover and as a frontispiece. It’s a mischievous poem, in that five owls are listening to a nightingale: ‘Our tree may be scarred / but that young flapper sings’. The author’s gloss compares the owls to ‘five patients waiting for wise Dr. Freud’. It is a clever conceit. Each owl speaks in turn and the fifth will put us in mind of a bird singing of what’s past, passing or to come – because (with no space on the main branch) it is therefore able to see clearly:

This is a fine example of what might almost be a Greening stock-in-trade. A more or less promising trigger is transformed into something playfully, often outlandishly, disturbing. Apparently, if the date is accurate, his grandfather would have been fifteen. I stand by ‘mischievous’, but it’s also somewhat chilling.

The opening section, PILGRIM, presents a challenged, even sardonic narrator playing against or within a theme, predominantly twenty-first century and leaning toward glimpses of enlightenment. From the Greening family home he could cycle to Molesworth or Little Gidding, so you’d expect him to emerge looking both ways. Or more likely three at somewhere like The Triangular Lodge near Rushton, Northants. It will not give up its secrets, not to Elizabeth’s spymasters nor to archaeological poets. Its surroundings seem strangely non-committal: ‘The intercity passes it, so does the road / to Rushton.’ A poet of place who so truly inhabits his subjects is quite rare I think. But whatever else Thomas Tresham’s famous token of resistance does, it will always resist.

It seems that Catholic Tresham’s ‘brick equation’ was never fully solved. The Tudor thought-police didn’t like it, but they couldn’t do him for it. Despite living close by for many years, even John Greening couldn’t get a tune out of it until 2021. That’s how resistant the place is. Similarly, there can be few of us who won’t have arrived At Little Gidding to find not much going on, but this deft-handed investigator puts it to use in a gentle parody of Larkin, complete with cycle-clips (Huntingdonshire Elegies, 2009). The whole collection is book-ended by Huntingdonshire Psalmody (Long Poem Magazine, 2017) and a lock-down piece entitled Aufklärung or ‘enlightenment’(Hudson Review, 2022). The former is an unashamedly nostalgic walk from skylarks to solar farm, uniting personal and universal contexts with a combination of intense sadness and forlorn hope. Some freedom of passage has been lost while a boundary is being regained because ‘someone is troubling to set…

Aufklärung is given a composition date of May, 2020 and is the most direct poem I’ve seen tackling the contradictory elements of lockdown. Its 104 hexameters in rhymed couplets defy brief quotation and uniquely capture an interwovenness of the time: ‘You are the mariner who knows he’s been / aboard the Marie Celeste and lived…’ There’s more than a little emotional loading when, after a so-called drumroll crescendo, it ends ironically: ‘You can disappear’.

And so to the editing. It is both joy and jolt to be confronted by eleven ‘mini-selecteds’ of thirty-odd pages organised by theme. Surprises and new relationships between poems abound. A transformative selection has much in common with a decluttered house, where stuff is lost and gained. It looks great, may even look ‘lived in’ – but where’s that gift you swore by? The homely sprawl of ‘Huntingdonshire Eclogues’, 32 poems in ‘Fotheringhay’ (1995) became 6 in ‘Nightflights’ (1998) and 21 in ‘Hunts’ (2009) but only creeps in here as Three Eclogues (‘Home’ section) plus two separate renamed poems: Airfields & Power Lines (‘Flight’ and ‘Intimations’ – two among several sections tight enough to entice yet loose enough to risk appearing random). Understandable given the enormity of choice, but I hope it’s for the shop window display and not a precursor to chipping away bits of the edifice. It may be tidy, and the assured poet may have fingers itching to tweak parts of the building, but the homely tercets of hexameters means they’ll stand apart wherever they’re placed, and there will always be reasons for keeping them together. That said, this collection lays down a challenge for all young poets approaching their seventies: how to be more profound, allusive and observant whilst also prolific and user-friendly. I struggle to grasp how he’s doing it, but I can see it’s being done. I’d want this book even if I owned the other two. It’s a treasure, hopefully to boost bucks and fame across the pond for one of our best, brightest and busiest poets of the last forty-odd years.