CORONATION STREETS: ENGLAND THEN AND NOW: John Lucas reflects upon Chris Arnot’s account of how England has changed since the 1953 coronation

Coronation Streets: England Then and Now

Chris Arnot

Takahe Publishing

ISBN 9781908837288

£11.95

Coronation Streets: England Then and Now

Chris Arnot

Takahe Publishing

ISBN 9781908837288

£11.95

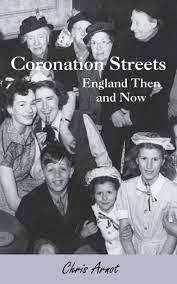

The image on the front cover of this informative and entertaining book tells you what to expect from the pages that follow. Chris Arnot’s genial, non-judgemental account of the England which some seventy years ago prepared to celebrate the coronation of the young woman ‘destined’ to be Elizabeth the Second is for the most part focussed on all those who planned for street parties and knees-ups. Hence the front-cover photograph. We are looking at a huddle of poorly-dressed women and children crowded together in a room which belongs, so Arnot tells us, to a public house in Derby called ‘The Exeter Arms.’ What on earth are they doing in such a place? How did they come to be there?

The answer, explanation if you like, is that this is Coronation Day, June 2nd, 1953, a day of rain, rain, and more rain, and the women and children are where they should not be because on this day of days the pub’s landlord has taken pity on them. Outside, rain hammers down, the street party with its planned-for ‘fun and games’ has been abandoned, and here they sit, the girls in party dresses and paper hats, while behind them mothers and grandmothers, clamped into a variety of shapeless, funereal-looking coats and bonnets, manage something near to a smile, and a solitary boy grins toothily at the camera, determined to assert a degree of quizzical enjoyment, though he would presumably far rather be with the men. But there are no men, not in this room, anyway. They must be elsewhere, probably shoulder to shoulder in the public bar, talking politics, or football, or cricket, or horses, or the dogs, or, even, the future of the monarchy.

And what is that future? Guaranteed, no doubt. We are a monarchical nation. Like death and taxes there will always be a king, or queen, to reign over us. The Second World War is eight years over, the re-building of bombed towns and cities has begun, and though rationing for clothes and food has by no means been abandoned – look again at the photograph, at those shapeless hats and drab coats, imagine the cucumber and jam and spam sandwiches intended for the now-sodden street tables – at least we have a new queen, ‘Radiant in Her Glory,’ so the newspapers tell us, the tories are back in power, Edmund Hillary has scaled Everest, God is in His Heaven, and despite the rain, the falling rain, and for all the mushroom clouds from nuclear tests that have been darkening South Pacific skies, we can listen as Billy Cotton’s Band Show brassily celebrates the Queen of Tonga who has come to England on Coronation Day, and despite the fact that in Korea and Malaya and, even, Cyprus, not to mention parts of Africa, British soldiers, including national servicemen, are fighting (and being killed), the sun will surely continue to shine on Our Empire. The Archbishop of Canterbury will declare it to be so, Richard Dimbleby will invert syntax to endorse majesty – ‘there stepped forth the young queen’ – and, never mind the damned rain, we shall have cakes (or ‘cates’ if you prefer) and ale.

Seventy years ago, I was fifteen years old, living with my parents and sister in Ashford, Middlesex (not, pace, the author, Kent, for though Arnot is kind enough to refer to Next Year Will Be Better, my account of England in the 1950s, he puts me in the wrong county.) My Ashford, pincered between Staines and Feltham, and securely of Middlesex until some year, later when county lines were re-drawn and Ashfordians were thenceforth pitched into Surrey, my Ashford was a small, featureless, outer London suburb with one cinema, a tea-shop, and a few pubs in whose back rooms occasional. Saturday-night dances did their best to alleviate the town’s decorous tedium. Further efforts of alleviation were provided in the wooden hall where the Anglican church’s Women’s Working Group laid on jumble sales; and, twice a year, dramatic performances of an earlier age’s West-End farces were rendered by the Ashford Parish. Players (my father was much in demand for his personation of country bumpkins, who, whether they supposedly came from outer Lancashire or the Lincolnshire wolds all spoke broad Devonian), while the equivalent Catholic hall shocked the rest of us by hosting all-the-year-round Sunday-evening dances, the mingled sounds of accordion music and stamping feet offending Ashford’s stilly night air from 7–10pm. Thump, thump, thump. Clogs and/or hob-nailed boots? Either way, scarcely respectable, though non-Catholics were comforted by the voiced realisation that after all Catholics were barely one up from barbarians.

Coronation Streets doesn’t much concern itself with the minutiae of the petty snobberies, the desperate clinging to proprieties that for so many post-war lives, all the way from upper working- to upper-middle class, provided a sense of achieved respectability. Those were years of the various unofficial sects who hugged to themselves a sense of being ‘special,’ ‘a bit above the Joneses, if you know what I mean,’ whether they claimed to be British Israelites, descended from the Apostle who had brought the Faith to England, or clung to the certain knowledge that trees along their street, even in their garden, were listed in the Domesday Book, so there. I remember one woman who became red-faced with fury when a man challenged her claim, made at some social event or other, that the wych elm behind her house went back to several hundreds of years before the Norman invasion. ‘But madam, such trees were only introduced to England in the seventeenth century.’ ‘Who do you think you are,’ she shouted at Doubting Thomas. And when he tried to explain that he was an arborealist she became incandescent. ‘I knew it,’ she yelled. ‘You’re not even a European, and they’re bad enough.’ And I was present when another woman, invited in for a cup of tea and a slice of sponge cake, told my mother that her husband’s roots could be traced to pre-Roman Britain. Shades of Hard Times, of Mrs Sparsit’s complacent revelation that her late husband was ‘a Powser.’

Poor, poor people. I used to be contemptuous of such threadbare, idiotic pretension. Now, I more often feel its sadness. But going with that is an anger prompted by the rottenness of a system embodied in those petty, ridiculous snobberies linked to the kind of social hierarchy that takes for granted and tries to endorse the rights of monarchy. ‘“God Save the King,”’ Byron wrote, quoted rather, before adding the sardonic ‘It is a large economy/In God to save the like.’ Yet still it goes on, the expenditure of that large economy. Still, squillions are made available for the royals and their houses and attendants. These people with their not-to-be questioned belief in their own authenticity. ‘Where are you from? Where are you really from?’ Why didn’t any of those who commented on that shameful enquiry know of, or quote from, Jackie Kay’s response, puzzled, irritated, to the woman who challenged the poet as to her, Jackie Kay’s origins. ‘“Here,” I say, “I’m from here.”’

From a kingdom of subjects to a democratic collective of citizens. From a monarchy to a sweet, equal republic. It still may not be within immediate reach, but it’s worth reaching for. I reach for my Dickens, I open Bleak House and I read that England is in a dreadful state, for the Coodles and the Boodles and the Duffys and the Buffys, who between them compose the entire identifiable nation, cannot be brought to agree as to which of them shall run the government. ‘A People there are, no doubt – a certain large number of supernumeraries, who are to be occasionally addressed and relied upon for shouts and choruses, as on the theatrical stage; but Boodle and Buffy, their followers and families, their heirs, executors, administrators, and assigns, are the born first actors, managers, and leaders, and no others can appear upon the scene for ever and ever.’ And of course over the Coodles and Doodles there is a Monarch, who also shall reign for ever and ever. Yea verily.

Bleak House, I have to pinch myself to remember, was written for getting on two hundred years ago, a hundred years before Dimbleby’s gasp of reverent wonder at the sight of Elizabeth stepping forth from the aeroplane that had brought her back to England on news of her father’s death so that she should assume the role of monarch, her accession to the throne thus bringing to an untimely end the African Safari during which she and her husband had been enjoying themselves by maiming and killing large numbers of wild, beautiful animals.

And to celebrate this selfless act of accession to the throne, the British populace was commanded to hold street parties. And yea, they vowed so to do, forthwith arraying themselves on that glorious morn of June 2nd 1953 in whatever finery they could muster until rain drove them indoors, though while the rain did douse and drench the land none was heard to complain that God must have forgotten the plot. Yet where, oh, where, was the sun which wise men of the cloth and others of secular distinction had confidently predicted would beam upon that day. Oh, it burnt in faithful hearts whilom patriots sang the National Anthem.

That as Arnot’s book allows us to see, was England then. And Now? It seems that now, so opinion polls reveal, fewer than a third of the younger generation have any interest in the monarchy. Well, good. I was slightly disappointed that Arnot doesn’t have much to say about the intervening years, of how and why this withering of regard for the monarchy has come about. On the other hand, his account of how England behaved, dressed and looked seventy years ago is bound to bring back vivid memories for those of us old enough to remember what the nation was like then, buttressed as Coronation Streets is by anecdote and telling detail, while younger readers are likely to be enthralled, even gape-mouthed, as they shake their heads over what must surely seem the sheer weirdness of that time.

Such weirdness survives in an image where comedy and pathos broadly combine. An old man in a peculiar uniform clambers into a golden coach so as to be trundled through London streets in order that the archbishop of a church to which few belong can proclaim him king of a nation which is for the most part indifferent to his existence and of an empire unlikely to survive for more than another generation. Weird or no? Yea Verily, or as Richard Dimbleby might have said, Verily Yea.

Jun 3 2023

CORONATION STREETS: ENGLAND THEN AND NOW

CORONATION STREETS: ENGLAND THEN AND NOW: John Lucas reflects upon Chris Arnot’s account of how England has changed since the 1953 coronation

The image on the front cover of this informative and entertaining book tells you what to expect from the pages that follow. Chris Arnot’s genial, non-judgemental account of the England which some seventy years ago prepared to celebrate the coronation of the young woman ‘destined’ to be Elizabeth the Second is for the most part focussed on all those who planned for street parties and knees-ups. Hence the front-cover photograph. We are looking at a huddle of poorly-dressed women and children crowded together in a room which belongs, so Arnot tells us, to a public house in Derby called ‘The Exeter Arms.’ What on earth are they doing in such a place? How did they come to be there?

The answer, explanation if you like, is that this is Coronation Day, June 2nd, 1953, a day of rain, rain, and more rain, and the women and children are where they should not be because on this day of days the pub’s landlord has taken pity on them. Outside, rain hammers down, the street party with its planned-for ‘fun and games’ has been abandoned, and here they sit, the girls in party dresses and paper hats, while behind them mothers and grandmothers, clamped into a variety of shapeless, funereal-looking coats and bonnets, manage something near to a smile, and a solitary boy grins toothily at the camera, determined to assert a degree of quizzical enjoyment, though he would presumably far rather be with the men. But there are no men, not in this room, anyway. They must be elsewhere, probably shoulder to shoulder in the public bar, talking politics, or football, or cricket, or horses, or the dogs, or, even, the future of the monarchy.

And what is that future? Guaranteed, no doubt. We are a monarchical nation. Like death and taxes there will always be a king, or queen, to reign over us. The Second World War is eight years over, the re-building of bombed towns and cities has begun, and though rationing for clothes and food has by no means been abandoned – look again at the photograph, at those shapeless hats and drab coats, imagine the cucumber and jam and spam sandwiches intended for the now-sodden street tables – at least we have a new queen, ‘Radiant in Her Glory,’ so the newspapers tell us, the tories are back in power, Edmund Hillary has scaled Everest, God is in His Heaven, and despite the rain, the falling rain, and for all the mushroom clouds from nuclear tests that have been darkening South Pacific skies, we can listen as Billy Cotton’s Band Show brassily celebrates the Queen of Tonga who has come to England on Coronation Day, and despite the fact that in Korea and Malaya and, even, Cyprus, not to mention parts of Africa, British soldiers, including national servicemen, are fighting (and being killed), the sun will surely continue to shine on Our Empire. The Archbishop of Canterbury will declare it to be so, Richard Dimbleby will invert syntax to endorse majesty – ‘there stepped forth the young queen’ – and, never mind the damned rain, we shall have cakes (or ‘cates’ if you prefer) and ale.

Seventy years ago, I was fifteen years old, living with my parents and sister in Ashford, Middlesex (not, pace, the author, Kent, for though Arnot is kind enough to refer to Next Year Will Be Better, my account of England in the 1950s, he puts me in the wrong county.) My Ashford, pincered between Staines and Feltham, and securely of Middlesex until some year, later when county lines were re-drawn and Ashfordians were thenceforth pitched into Surrey, my Ashford was a small, featureless, outer London suburb with one cinema, a tea-shop, and a few pubs in whose back rooms occasional. Saturday-night dances did their best to alleviate the town’s decorous tedium. Further efforts of alleviation were provided in the wooden hall where the Anglican church’s Women’s Working Group laid on jumble sales; and, twice a year, dramatic performances of an earlier age’s West-End farces were rendered by the Ashford Parish. Players (my father was much in demand for his personation of country bumpkins, who, whether they supposedly came from outer Lancashire or the Lincolnshire wolds all spoke broad Devonian), while the equivalent Catholic hall shocked the rest of us by hosting all-the-year-round Sunday-evening dances, the mingled sounds of accordion music and stamping feet offending Ashford’s stilly night air from 7–10pm. Thump, thump, thump. Clogs and/or hob-nailed boots? Either way, scarcely respectable, though non-Catholics were comforted by the voiced realisation that after all Catholics were barely one up from barbarians.

Coronation Streets doesn’t much concern itself with the minutiae of the petty snobberies, the desperate clinging to proprieties that for so many post-war lives, all the way from upper working- to upper-middle class, provided a sense of achieved respectability. Those were years of the various unofficial sects who hugged to themselves a sense of being ‘special,’ ‘a bit above the Joneses, if you know what I mean,’ whether they claimed to be British Israelites, descended from the Apostle who had brought the Faith to England, or clung to the certain knowledge that trees along their street, even in their garden, were listed in the Domesday Book, so there. I remember one woman who became red-faced with fury when a man challenged her claim, made at some social event or other, that the wych elm behind her house went back to several hundreds of years before the Norman invasion. ‘But madam, such trees were only introduced to England in the seventeenth century.’ ‘Who do you think you are,’ she shouted at Doubting Thomas. And when he tried to explain that he was an arborealist she became incandescent. ‘I knew it,’ she yelled. ‘You’re not even a European, and they’re bad enough.’ And I was present when another woman, invited in for a cup of tea and a slice of sponge cake, told my mother that her husband’s roots could be traced to pre-Roman Britain. Shades of Hard Times, of Mrs Sparsit’s complacent revelation that her late husband was ‘a Powser.’

Poor, poor people. I used to be contemptuous of such threadbare, idiotic pretension. Now, I more often feel its sadness. But going with that is an anger prompted by the rottenness of a system embodied in those petty, ridiculous snobberies linked to the kind of social hierarchy that takes for granted and tries to endorse the rights of monarchy. ‘“God Save the King,”’ Byron wrote, quoted rather, before adding the sardonic ‘It is a large economy/In God to save the like.’ Yet still it goes on, the expenditure of that large economy. Still, squillions are made available for the royals and their houses and attendants. These people with their not-to-be questioned belief in their own authenticity. ‘Where are you from? Where are you really from?’ Why didn’t any of those who commented on that shameful enquiry know of, or quote from, Jackie Kay’s response, puzzled, irritated, to the woman who challenged the poet as to her, Jackie Kay’s origins. ‘“Here,” I say, “I’m from here.”’

From a kingdom of subjects to a democratic collective of citizens. From a monarchy to a sweet, equal republic. It still may not be within immediate reach, but it’s worth reaching for. I reach for my Dickens, I open Bleak House and I read that England is in a dreadful state, for the Coodles and the Boodles and the Duffys and the Buffys, who between them compose the entire identifiable nation, cannot be brought to agree as to which of them shall run the government. ‘A People there are, no doubt – a certain large number of supernumeraries, who are to be occasionally addressed and relied upon for shouts and choruses, as on the theatrical stage; but Boodle and Buffy, their followers and families, their heirs, executors, administrators, and assigns, are the born first actors, managers, and leaders, and no others can appear upon the scene for ever and ever.’ And of course over the Coodles and Doodles there is a Monarch, who also shall reign for ever and ever. Yea verily.

Bleak House, I have to pinch myself to remember, was written for getting on two hundred years ago, a hundred years before Dimbleby’s gasp of reverent wonder at the sight of Elizabeth stepping forth from the aeroplane that had brought her back to England on news of her father’s death so that she should assume the role of monarch, her accession to the throne thus bringing to an untimely end the African Safari during which she and her husband had been enjoying themselves by maiming and killing large numbers of wild, beautiful animals.

And to celebrate this selfless act of accession to the throne, the British populace was commanded to hold street parties. And yea, they vowed so to do, forthwith arraying themselves on that glorious morn of June 2nd 1953 in whatever finery they could muster until rain drove them indoors, though while the rain did douse and drench the land none was heard to complain that God must have forgotten the plot. Yet where, oh, where, was the sun which wise men of the cloth and others of secular distinction had confidently predicted would beam upon that day. Oh, it burnt in faithful hearts whilom patriots sang the National Anthem.

That as Arnot’s book allows us to see, was England then. And Now? It seems that now, so opinion polls reveal, fewer than a third of the younger generation have any interest in the monarchy. Well, good. I was slightly disappointed that Arnot doesn’t have much to say about the intervening years, of how and why this withering of regard for the monarchy has come about. On the other hand, his account of how England behaved, dressed and looked seventy years ago is bound to bring back vivid memories for those of us old enough to remember what the nation was like then, buttressed as Coronation Streets is by anecdote and telling detail, while younger readers are likely to be enthralled, even gape-mouthed, as they shake their heads over what must surely seem the sheer weirdness of that time.

Such weirdness survives in an image where comedy and pathos broadly combine. An old man in a peculiar uniform clambers into a golden coach so as to be trundled through London streets in order that the archbishop of a church to which few belong can proclaim him king of a nation which is for the most part indifferent to his existence and of an empire unlikely to survive for more than another generation. Weird or no? Yea Verily, or as Richard Dimbleby might have said, Verily Yea.