THINGS: Charles Rammelkamp reviews a flash fiction collection by Peter Cherches

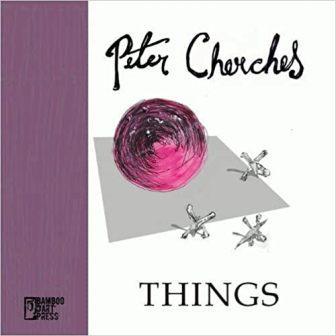

Things

Peter Cherches

Bamboo Dart Press

ISBN: 978-1-947240-74-2

62 pages $8.99

Things

Peter Cherches

Bamboo Dart Press

ISBN: 978-1-947240-74-2

62 pages $8.99

My wife and I play a game with each other. One of us will announce, “I’m going to that place to do that thing.” “What thing?” “That stuff. I’m going to get that stuff.” Either we remember from a previous conversation, or we remain in the dark. This same delicious ambiguity is at work in Peter Cherches’ delightful new collection of poetry and flash – flash fiction, flash essays, flash riddles, “stuff” that makes you chuckle or say, “wait a minute….”

For instance, in the story “Strandgallier” the protagonist tells us that he wanted to buy a new strandgallier; his old one, which he’s had all his life, is on the fritz. But he couldn’t find one on Amazon or Ebay, and Google? It offered a guitar, a bench, a “Stranda Descender Split 22/23 Splitboard.” And all he wanted was “a simple, garden-variety strandgallier.” Of course, I fell for it, knowing all along I was on a fool’s errand, and googled the word myself. I got hits for Crystal chakra healing collection ideas and an address for an art gallery. I could almost hear Cherches laughing – “gotcha!”

The collection starts out with “Another Thing” (well, the second story in): “She told me I had another thing coming to me.” There’s no other thing, which puzzles and then enrages the speaker when the other thing turns out to be this and that. Words standing for words. Or for things. It’s all perfectly abstract, but that doesn’t mean the emotional impact is any less real, less concrete.

Cherches’ sardonic humor is all over these forty-seven pieces. One particularly amusing example is called “No Ideas but in Things,” which plays on William Carlos Williams’ Imagist maxim about poetics, from his poem, “A Sort of a Song.” Cherches begins the story, “A thing had an idea. Another thing had a different idea.” The two things have an argument about their ideas. In a couple of stories Cherches has fun with Kafka. “The Loneliness Vendor” echoes Kafka’s famous story, “The Hunger Artist,” and “The Metamorphosis,” of course, is another parody. It begins: “As Ludlow St. John awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a thing. A mere thing.” Gertrude Stein is another springboard for his quirky humor. The repetition in “No Name” (“She came. She came. She came.”) sounds so much like Stein’s famous “A rose is a rose is a rose.” The story “Dialogue” repeats the speeches of two people sixteen times:

“It is what it is.”

“Whatever.”

Cherches has the same thing with things that indecisive Hamlet has – “The play’s the thing,” “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy”; “The king is a thing,” to which Guildenstern responds, “A thing, my lord?” “Of nothing,” replies Hamlet, the prince of indecision. Sounds like dialogue that could come from this book!

Cherches plays on indecisiveness, on the imprecision of “thing,” over and over. In the story, “Limited Edition,” without using the word “thing,” Cherches still exloits the vagueness. “Only five were ever produced,” he writes, “a very limited edition.” We never do find out what these rare creations are, only that one hangs in Shelly Kaminsky’s living room. Similarly, in “A Dry One,” a wife, Delilah, becomes incensed when she sees the “soaking piece of crap” her husband has brought her for their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, damaged by rain, and she moves in with his brother, with whom she’s been having an affair for the past quarter century. We’re never told what that offensive gift is!

“Better Than That” is a clever tale in which a man and a woman wonder if an unidentified “thing” is safe to eat. She suggests they feed it to an animal. He objects to the cruelty. She agrees with him. “‘You’re right,’ she said. ‘You try it.’” The story “Flavors” likewise explores the taste of certain vaguely described objects. “Bringing It Up” sums up the whole process. The story reads in its entirety:

“I haven’t thought about that in years,” he told her when she

brought it up.

“Oh really?” she said. “I’ve never stopped thinking about it.”

The collection also includes a handful of poems, several of them pantoums, whose very coiled repetition of lines makes the form so appropriate for this group of “things.” “How to Write an Effective Composition” (“Narrow it down until there’s nothing left.”), “Sacco’s Speech” (“I am not an orator.”), “Unwritten Poem”:

I can take any blank page and call it

An unwritten poem.

That part is easy enough.

The real challenge is to write it.

What a conundrum! The poem, “haiku” encapsulates the impulse:

there are just some things

you don’t say in a haiku

like this for instance

Peter Cherches’ droll humor and philosophical intelligence make Things a real delight to read, elliptical as Zen koans, almost as if the poet is letting us in on a secret, or as if we are sharing a private joke.

Apr 3 2023

THINGS

THINGS: Charles Rammelkamp reviews a flash fiction collection by Peter Cherches

My wife and I play a game with each other. One of us will announce, “I’m going to that place to do that thing.” “What thing?” “That stuff. I’m going to get that stuff.” Either we remember from a previous conversation, or we remain in the dark. This same delicious ambiguity is at work in Peter Cherches’ delightful new collection of poetry and flash – flash fiction, flash essays, flash riddles, “stuff” that makes you chuckle or say, “wait a minute….”

For instance, in the story “Strandgallier” the protagonist tells us that he wanted to buy a new strandgallier; his old one, which he’s had all his life, is on the fritz. But he couldn’t find one on Amazon or Ebay, and Google? It offered a guitar, a bench, a “Stranda Descender Split 22/23 Splitboard.” And all he wanted was “a simple, garden-variety strandgallier.” Of course, I fell for it, knowing all along I was on a fool’s errand, and googled the word myself. I got hits for Crystal chakra healing collection ideas and an address for an art gallery. I could almost hear Cherches laughing – “gotcha!”

The collection starts out with “Another Thing” (well, the second story in): “She told me I had another thing coming to me.” There’s no other thing, which puzzles and then enrages the speaker when the other thing turns out to be this and that. Words standing for words. Or for things. It’s all perfectly abstract, but that doesn’t mean the emotional impact is any less real, less concrete.

Cherches’ sardonic humor is all over these forty-seven pieces. One particularly amusing example is called “No Ideas but in Things,” which plays on William Carlos Williams’ Imagist maxim about poetics, from his poem, “A Sort of a Song.” Cherches begins the story, “A thing had an idea. Another thing had a different idea.” The two things have an argument about their ideas. In a couple of stories Cherches has fun with Kafka. “The Loneliness Vendor” echoes Kafka’s famous story, “The Hunger Artist,” and “The Metamorphosis,” of course, is another parody. It begins: “As Ludlow St. John awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a thing. A mere thing.” Gertrude Stein is another springboard for his quirky humor. The repetition in “No Name” (“She came. She came. She came.”) sounds so much like Stein’s famous “A rose is a rose is a rose.” The story “Dialogue” repeats the speeches of two people sixteen times:

Cherches has the same thing with things that indecisive Hamlet has – “The play’s the thing,” “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy”; “The king is a thing,” to which Guildenstern responds, “A thing, my lord?” “Of nothing,” replies Hamlet, the prince of indecision. Sounds like dialogue that could come from this book!

Cherches plays on indecisiveness, on the imprecision of “thing,” over and over. In the story, “Limited Edition,” without using the word “thing,” Cherches still exloits the vagueness. “Only five were ever produced,” he writes, “a very limited edition.” We never do find out what these rare creations are, only that one hangs in Shelly Kaminsky’s living room. Similarly, in “A Dry One,” a wife, Delilah, becomes incensed when she sees the “soaking piece of crap” her husband has brought her for their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, damaged by rain, and she moves in with his brother, with whom she’s been having an affair for the past quarter century. We’re never told what that offensive gift is!

“Better Than That” is a clever tale in which a man and a woman wonder if an unidentified “thing” is safe to eat. She suggests they feed it to an animal. He objects to the cruelty. She agrees with him. “‘You’re right,’ she said. ‘You try it.’” The story “Flavors” likewise explores the taste of certain vaguely described objects. “Bringing It Up” sums up the whole process. The story reads in its entirety:

The collection also includes a handful of poems, several of them pantoums, whose very coiled repetition of lines makes the form so appropriate for this group of “things.” “How to Write an Effective Composition” (“Narrow it down until there’s nothing left.”), “Sacco’s Speech” (“I am not an orator.”), “Unwritten Poem”:

What a conundrum! The poem, “haiku” encapsulates the impulse:

Peter Cherches’ droll humor and philosophical intelligence make Things a real delight to read, elliptical as Zen koans, almost as if the poet is letting us in on a secret, or as if we are sharing a private joke.