Poetry review – ROCK, BIRD, BUTTERFLY: Pam Thompson takes a close look at Hannah Lowe’s delightful poetic examination of 18th century Chinese wallpapers

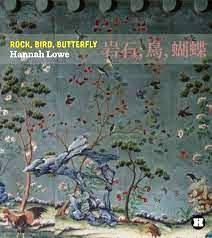

Rock, Bird, Butterfly

Hannah Lowe

Hercules Editions

ISBN 9 78196 197183

39pp. £10

Rock, Bird, Butterfly

Hannah Lowe

Hercules Editions

ISBN 9 78196 197183

39pp. £10

This elegant square pamphlet from Hercules Editions continues Hannah Lowe’s exploration of the Chinese diaspora in Europe and was published simultaneously (and by the same publisher) with Old Friends, a collection with the theme of London’s first Chinatown, Limehouse. The subject is a niche one, Chinese wallpaper, and the poems, characteristically for this series, are bookended by two essays, one from an academic ‘expert’ and one from a poet, in this case, Hannah Lowe herself.

The Introduction, ‘Chinese wallpaper, a global commodity?’ by Clare Taylor, a Senior Lecturer in Art History, who specialises in interiors and decoration, gives context and background, especially about predilection for items of East-Asian art and design, a taste known as ‘chinoiserie’. There was a certain exclusivity about how the wallpapers were traded, changing hands privately, at auctions or as gifts. Their appeal lay in their limited, decorative nature, and in their depictions of nature, often with an amalgamation of various elements to reflect European tastes for Chinese-style gardens. Other designs focused on the activities of the leisured classes, fitting for an elite who could afford them. Taylor gives some idea where the wallpapers might have been hung – in the 18th century, usually in bedrooms and dressing rooms of female aristocrats. Controversy lay in what was behind such exclusivity: the poem, ‘The Mines’ gives an example of an aristocratic property and its furnishings that arises from the slave trade.

This fascinating background paves the way for Lowe’s imaginative exploration of some of this history, acknowledging the contradictions and complexities. The poems bring unknown people and unknown stories to light but also issues related to commodification and Lowe’s own complicated relationship to chinoiserie.

There are twelve poems. Most pages include text with an accompanying illustration from a wallpaper. Lowe can turn her hand to many forms but has a certain ease with the sonnet, and near-sonnet. The pamphlet opens with ‘Dazzling Blue’, five stanzas of seven lines where the poet expresses her enthusiasm for Chinese wallpaper, “I laugh, scrolling through my phone, consider / this dazzling blue!’, and so we do too, in the exuberance of the poem in conjunction with the illustration opposite: an ornate peacock on a blue tree branch against a blue sky. The poet bubbles over with excitement about the new project to a poet friend:

and when I tell Arji

I’m writing wallpaper poems, or am meant to be

but don’t know what to write, he empathises

deeply, relating my experience to his

as poet-in-residence at Wedgewood Pottery –

Wedgewood! He sighs, like what did I know

about Wedgewood?

I take this ‘friend’ to be Arji Manuelpillai, who was mentored by Lowe, showing that even well-known poets may not always find it easy to find a position themselves within the projects they take on. The poet/speaker goes on to tell a dramatic story about wallpaper on show at Coutts, the private bank, saved from a sinking clipper in the throes of a pirate attack, ‘£26 for one sheet of paper!’ The exclamation mark speaks for her and our astonishment.

There are so many unknowns about Chinese artefacts and their trading histories. These, are articulated in the questions in the seven brief couplets in, ‘If the Wallpaper Could Speak?’:

Would anyone listen to its tales

of ocean, pirates, ship wrecks,

a blue-print teapot sinking

through salt water, a grave

of porcelain at the bottom of the sea?

Silences are insidious as gaps in histories or deliberate omissions about the nature of the export trade and responsibility for its origins and practices. ‘The Mines’, a sonnet, introduces Lord Penryn, who, in his Welsh castle, follows the trend of the wealthy elite, ‘Anyone who was anyone had to have / a China room , and Lord Penrhyn had two …’. All the ostentation is a proclamation of power. Metaphorically, ‘the bragging mouth of his grand front door’, sums it up excellently. The door was raised so he a better view across his territory, particularly the slate mines, financed by slave labour, ‘(six hundred slaves on three / plantations he’d never seen)’. There is a coda to the poem where words from the poem are added to others with forward-slashes between them. Perhaps this works orally better than visually? Whatever, it doesn’t let us ignore the chain of commodification which allows Penrhyn to exhort his wealth.

slave/slate/slave/slate/slave/slate/plantation/valley/

plantation/quarry/sugar/slate/sugar/slate/slave/slate/

slave/slate/cane/slate/cane/slate/sugar/slave/slate/money

Even when wallpaper went out of fashion was replaced by more conventional British prints, it’s presence is evident after a fire in one of the stately homes, ‘little scalded scraps – though still flamboyant – / red peonies, gold magnolia …’. (‘Uppark’)

It is amazing that so little was known about how and where the wallpapers were made. Against an illustration of two stylised ducks is a short poem whose tone projects the likely disgruntlement of the person who block-printed the ducks, being anonymous and unsung during the process:

If you had a wen for every

duck you’ve stamped

on paper or silk

you’d ditch this life

and take your wife and kids

to the mountains

You can see how individual details of the wallpaper would be transfixing, as is the scarlet peony for the poet/speaker in ‘Om’. As the curator is explaining the hanging of paintings, this one detail takes the speaker back to thoughts of Sunday yoga and the instructor, Luana, saying that the ‘drishti’ is ‘a focal point to fix the gaze’. ‘Om’, of course is an ancient chant which links contemporary yoga practice with it through history., In the final three lines of the poem, a synaesthaetic turn, we’re reminded that sound and image can be as ‘loud ‘as each other, and are connectives between periods of time. The chant:

an ancient-sounding chorus,

perfect in its tone and harmony,

but for the topless man in front of me

blindly singing, louder than us all

like a too-red flower slapped to a wall.

‘The Hanger’ is a monologue in the voice of Jonah Button who was one of the few experts who could hang the wallpapers properly. The poem speaks to trends, and of experts. I liked the pun in the opening line, ‘Now that the orient’s in fashion, I’m on a roll …’, and the recognition of his absolute worth, ‘without the Hanger, there is no Chinese room.’

‘Long Elizas’ is seven couplets and two extended questions, the first ending with speculation whether or not ‘bored and beautiful English ladies’, compared their lives and their fashions to the ‘willowy figures’ on their parlour’s wallpaper? The rarefied atmosphere is exaggerated, the soft chatter and decorous pouring of tea, offset against the images of ‘the painted Chinamen, stamping tea-leaves, packing tea in crates, to ship five thousand miles across the seas.’

The topic of Chinese wallpaper particularly appealed to Lowe’s imagination because of her Chinese grandfather about whom she knew very little, so, understandably, she invested the Chinese objects and art in the house with made-up stories. Even as an adult she defended her father’s wall hangings after his death, hanging them on her own wall and ‘If anyone asked, I called them heirlooms /from my father’s father’s village … / though I knew // he’d bought them in Soho’. (‘Chinese Wall Hangings’)

A faint green Chinese dragon underlies the two pages of ‘The Look of Things’ where Lowe recalls the chinoiserie in her life, her home and clothes. She is honest about liking ‘the look of things Chinese’, whether it is a skirt or a notebooks, ‘with no understanding of its printing culture / or bird or flower iconography’. This may be reassuring for many of us. She acknowledges nothing is of itself, a cultural monolith, ‘even I’m a version of a version of a version – / always some detail is lost in reproduction.’

In the Afterword, Lowe relates how her explorations around Chinese wallpapers originated in a commission with nine other writers-from the University of Leicester’s ‘Colonial Countryside’ project, whose aim was to retell the stories of Britain’s great country houses and to demand that their historical links with the British Empire and colonial profiteering be more fully acknowledged.

This research process is very much highlighted in the poems. For‘The Curator’ Lowe finds some personal information online, and on ‘his blog, his Twitter feed’, but what interests her most is ‘the spark that set his fire’. She quotes examples from her own family, none of whom are dull: the psychoanalyst brother whose interest may have been sparked by a family ghost; the grandfather who was a book collector, who became interested the Hindu religion, ‘shunned his family, his class, to marry / his cleaner’. There is Britain’s leading expert on Chinatown, a woman, who, like Lowe herself, loved Chinese things passed down through the family. Just as her attention was transfixed by the image of the red peony, she imagines the curator being likewise transported, by close attention to, for instance, ‘a papered parakeet, a flaming peacock, / … two scholar’s rocks’.

‘Travel Papers’ opens with a reference to the British firm, de Gournay which went to manufacture in China in the 1930s and who ‘sell ‘St Laurent’ at £500 per roll’. It was named for Yves St Laurent, ‘in memory of the historic paper / that hung in the Parisian apartment / of Pierre Bergé, his lover’, and so the poem ‘unrolls’, from one rich US house and owner to another, set against the wallpaper, and its counterpart ‘the paper hung at Abbotsford House / on the Scottish Borders:

and must, the experts think, have been made

at the same painting workshop

somewhere in Guangzhou, three hundred years ago.

The pamphlet’s final poem takes yet another tangent. The poet is reading a book called Mr Foote’s Other Leg in the London Library while, at the same time, outside, a man in a suit is dancing, ‘kicking his legs from /side to side, a hip-hop tango’. The book, about the trial of Samuel Foote for sodomy, used Chinese wallpaper as key evidence of Foote’s guilt:

Foote’s coachman ‘Sangsty’

named the sitting room’s bare walls and rolls

of paper waiting to be hung

as proof he’d seen the Suffolk Street interior.

where Mr Foote – ‘one legged buggerer’ –

pleaded ‘let me have a fuck at you!

A servant would not be allowed in the private living rooms of an employer. We have already learnt in the Introduction to the pamphlet that wallpaper was hung in the more ‘intimate’ spaces of a house. The poem ends with the dancing man almost shifting out of the poet’s vision and the conclusion supplies a fitting coda to the whole:

The book is well researched and readable.

But, history, like these two men in the street

below, is something in sight, and out of view.

Hannah Lowe throws different slants on her fascinating subject in poems which are consistently engaging and the pamphlet is a gorgeous object to hold in your hands.

Mar 3 2023

London Grip Poetry Review – Hannah Lowe

Poetry review – ROCK, BIRD, BUTTERFLY: Pam Thompson takes a close look at Hannah Lowe’s delightful poetic examination of 18th century Chinese wallpapers

This elegant square pamphlet from Hercules Editions continues Hannah Lowe’s exploration of the Chinese diaspora in Europe and was published simultaneously (and by the same publisher) with Old Friends, a collection with the theme of London’s first Chinatown, Limehouse. The subject is a niche one, Chinese wallpaper, and the poems, characteristically for this series, are bookended by two essays, one from an academic ‘expert’ and one from a poet, in this case, Hannah Lowe herself.

The Introduction, ‘Chinese wallpaper, a global commodity?’ by Clare Taylor, a Senior Lecturer in Art History, who specialises in interiors and decoration, gives context and background, especially about predilection for items of East-Asian art and design, a taste known as ‘chinoiserie’. There was a certain exclusivity about how the wallpapers were traded, changing hands privately, at auctions or as gifts. Their appeal lay in their limited, decorative nature, and in their depictions of nature, often with an amalgamation of various elements to reflect European tastes for Chinese-style gardens. Other designs focused on the activities of the leisured classes, fitting for an elite who could afford them. Taylor gives some idea where the wallpapers might have been hung – in the 18th century, usually in bedrooms and dressing rooms of female aristocrats. Controversy lay in what was behind such exclusivity: the poem, ‘The Mines’ gives an example of an aristocratic property and its furnishings that arises from the slave trade.

This fascinating background paves the way for Lowe’s imaginative exploration of some of this history, acknowledging the contradictions and complexities. The poems bring unknown people and unknown stories to light but also issues related to commodification and Lowe’s own complicated relationship to chinoiserie.

There are twelve poems. Most pages include text with an accompanying illustration from a wallpaper. Lowe can turn her hand to many forms but has a certain ease with the sonnet, and near-sonnet. The pamphlet opens with ‘Dazzling Blue’, five stanzas of seven lines where the poet expresses her enthusiasm for Chinese wallpaper, “I laugh, scrolling through my phone, consider / this dazzling blue!’, and so we do too, in the exuberance of the poem in conjunction with the illustration opposite: an ornate peacock on a blue tree branch against a blue sky. The poet bubbles over with excitement about the new project to a poet friend:

I take this ‘friend’ to be Arji Manuelpillai, who was mentored by Lowe, showing that even well-known poets may not always find it easy to find a position themselves within the projects they take on. The poet/speaker goes on to tell a dramatic story about wallpaper on show at Coutts, the private bank, saved from a sinking clipper in the throes of a pirate attack, ‘£26 for one sheet of paper!’ The exclamation mark speaks for her and our astonishment.

There are so many unknowns about Chinese artefacts and their trading histories. These, are articulated in the questions in the seven brief couplets in, ‘If the Wallpaper Could Speak?’:

Silences are insidious as gaps in histories or deliberate omissions about the nature of the export trade and responsibility for its origins and practices. ‘The Mines’, a sonnet, introduces Lord Penryn, who, in his Welsh castle, follows the trend of the wealthy elite, ‘Anyone who was anyone had to have / a China room , and Lord Penrhyn had two …’. All the ostentation is a proclamation of power. Metaphorically, ‘the bragging mouth of his grand front door’, sums it up excellently. The door was raised so he a better view across his territory, particularly the slate mines, financed by slave labour, ‘(six hundred slaves on three / plantations he’d never seen)’. There is a coda to the poem where words from the poem are added to others with forward-slashes between them. Perhaps this works orally better than visually? Whatever, it doesn’t let us ignore the chain of commodification which allows Penrhyn to exhort his wealth.

Even when wallpaper went out of fashion was replaced by more conventional British prints, it’s presence is evident after a fire in one of the stately homes, ‘little scalded scraps – though still flamboyant – / red peonies, gold magnolia …’. (‘Uppark’)

It is amazing that so little was known about how and where the wallpapers were made. Against an illustration of two stylised ducks is a short poem whose tone projects the likely disgruntlement of the person who block-printed the ducks, being anonymous and unsung during the process:

You can see how individual details of the wallpaper would be transfixing, as is the scarlet peony for the poet/speaker in ‘Om’. As the curator is explaining the hanging of paintings, this one detail takes the speaker back to thoughts of Sunday yoga and the instructor, Luana, saying that the ‘drishti’ is ‘a focal point to fix the gaze’. ‘Om’, of course is an ancient chant which links contemporary yoga practice with it through history., In the final three lines of the poem, a synaesthaetic turn, we’re reminded that sound and image can be as ‘loud ‘as each other, and are connectives between periods of time. The chant:

‘The Hanger’ is a monologue in the voice of Jonah Button who was one of the few experts who could hang the wallpapers properly. The poem speaks to trends, and of experts. I liked the pun in the opening line, ‘Now that the orient’s in fashion, I’m on a roll …’, and the recognition of his absolute worth, ‘without the Hanger, there is no Chinese room.’

‘Long Elizas’ is seven couplets and two extended questions, the first ending with speculation whether or not ‘bored and beautiful English ladies’, compared their lives and their fashions to the ‘willowy figures’ on their parlour’s wallpaper? The rarefied atmosphere is exaggerated, the soft chatter and decorous pouring of tea, offset against the images of ‘the painted Chinamen, stamping tea-leaves, packing tea in crates, to ship five thousand miles across the seas.’

The topic of Chinese wallpaper particularly appealed to Lowe’s imagination because of her Chinese grandfather about whom she knew very little, so, understandably, she invested the Chinese objects and art in the house with made-up stories. Even as an adult she defended her father’s wall hangings after his death, hanging them on her own wall and ‘If anyone asked, I called them heirlooms /from my father’s father’s village … / though I knew // he’d bought them in Soho’. (‘Chinese Wall Hangings’)

A faint green Chinese dragon underlies the two pages of ‘The Look of Things’ where Lowe recalls the chinoiserie in her life, her home and clothes. She is honest about liking ‘the look of things Chinese’, whether it is a skirt or a notebooks, ‘with no understanding of its printing culture / or bird or flower iconography’. This may be reassuring for many of us. She acknowledges nothing is of itself, a cultural monolith, ‘even I’m a version of a version of a version – / always some detail is lost in reproduction.’

In the Afterword, Lowe relates how her explorations around Chinese wallpapers originated in a commission with nine other writers-from the University of Leicester’s ‘Colonial Countryside’ project, whose aim was to retell the stories of Britain’s great country houses and to demand that their historical links with the British Empire and colonial profiteering be more fully acknowledged.

This research process is very much highlighted in the poems. For‘The Curator’ Lowe finds some personal information online, and on ‘his blog, his Twitter feed’, but what interests her most is ‘the spark that set his fire’. She quotes examples from her own family, none of whom are dull: the psychoanalyst brother whose interest may have been sparked by a family ghost; the grandfather who was a book collector, who became interested the Hindu religion, ‘shunned his family, his class, to marry / his cleaner’. There is Britain’s leading expert on Chinatown, a woman, who, like Lowe herself, loved Chinese things passed down through the family. Just as her attention was transfixed by the image of the red peony, she imagines the curator being likewise transported, by close attention to, for instance, ‘a papered parakeet, a flaming peacock, / … two scholar’s rocks’.

‘Travel Papers’ opens with a reference to the British firm, de Gournay which went to manufacture in China in the 1930s and who ‘sell ‘St Laurent’ at £500 per roll’. It was named for Yves St Laurent, ‘in memory of the historic paper / that hung in the Parisian apartment / of Pierre Bergé, his lover’, and so the poem ‘unrolls’, from one rich US house and owner to another, set against the wallpaper, and its counterpart ‘the paper hung at Abbotsford House / on the Scottish Borders:

The pamphlet’s final poem takes yet another tangent. The poet is reading a book called Mr Foote’s Other Leg in the London Library while, at the same time, outside, a man in a suit is dancing, ‘kicking his legs from /side to side, a hip-hop tango’. The book, about the trial of Samuel Foote for sodomy, used Chinese wallpaper as key evidence of Foote’s guilt:

A servant would not be allowed in the private living rooms of an employer. We have already learnt in the Introduction to the pamphlet that wallpaper was hung in the more ‘intimate’ spaces of a house. The poem ends with the dancing man almost shifting out of the poet’s vision and the conclusion supplies a fitting coda to the whole:

Hannah Lowe throws different slants on her fascinating subject in poems which are consistently engaging and the pamphlet is a gorgeous object to hold in your hands.